There are numerous articles and studies on the average earnings of college graduates broken down by what they majored in when in college. Some provide estimates for a comprehensive list of college majors, while some focus on the earnings of the top 10 or bottom 10 ten college majors. Some focus on earnings soon after college graduation, some on earnings at mid-career, and some on earnings over a lifetime. And some use private sources of data while others use publicly available data provided by the Census Bureau or some other government agency. See, as examples, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, or here.

Also, some report average earnings while some report median earnings (where 50% of the individuals earn more and 50% earn less). But all focus on such a single measure of the earnings a graduate might expect had they chosen to major in a given field of study.

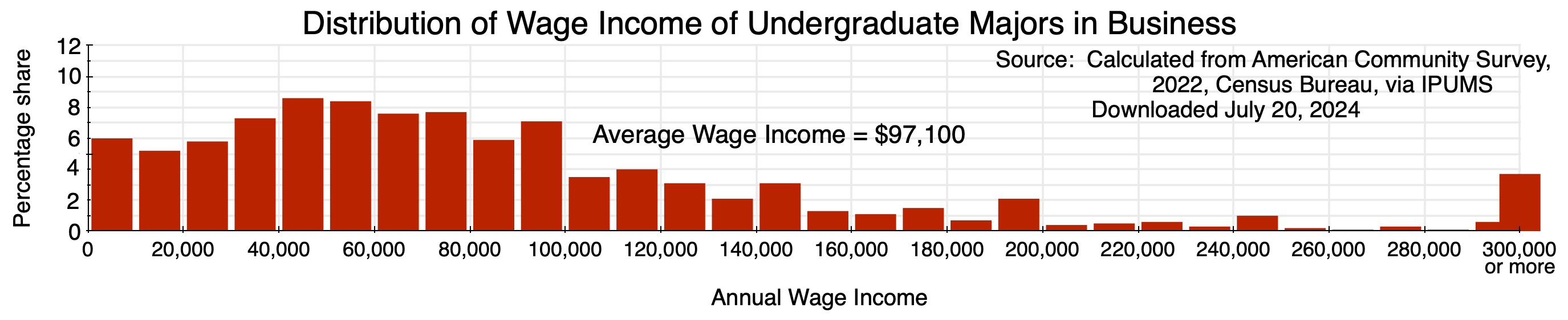

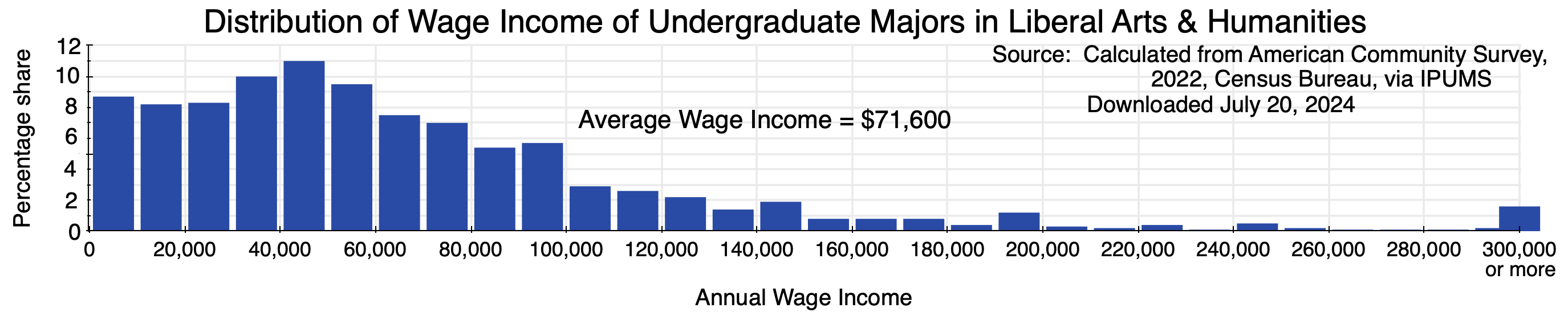

This misses a lot. No one earns the average nor the median. There is, rather, a range of earnings above and below those average (or median) figures, and as we see in the charts at the top of this post, it is a very wide range. The distributions overlap each other a lot, and the peak share is not all that high.

In the examples presented above, the average wage and salary earnings of those who majored in Business ($97,100) are more than a third higher than the average earnings of those who majored in one of the fields in the Liberal Arts & Humanities ($71,600). (The source of the data for these estimates is discussed in a note at the end of this post.) But despite the average for Business majors being more than a third higher, the earnings at the top end (the top third, say) of those who majored in one of the Liberal Arts & Humanities fields were far higher than the earnings of those who were at the bottom end (the bottom third, say) for the Business majors.

That is, it is not just the averages that matter. It is much more important whether your earnings will be towards the top end of a given field rather than closer to the bottom end of some alternative field, even if average earnings in that alternative field may be higher. The choices students make on what field to study in college can and should take this into account.

Instead of deciding to major in some field where the numerous articles available advise you may earn a higher income on average, it is far more worthwhile and consequential to decide on a field of study based on where you believe you can do well: a field you can fully master and where you perform exceptionally well, and thus where there is good reason to expect you will be able to do better than others in that area. Indeed, you should only major in a field where you have a sound basis for the belief you can be at or close to the very top in that field.

This will likely also be a field that you personally enjoy. Expertise in a field and personal enjoyment in it usually go hand-in-hand. You enjoy working in areas that you are good at. And due to the broad overlap in the distributions of earnings across the different fields, this will likely also lead to far higher earnings than majoring in a field that one is not terribly good at, even if the average earnings in that field are higher.

There is, or at least there should be, of course much more than earnings to consider. But this is a further reason to choose a field based on what one is good at, as that will likely lead to a more fulfilling career as well.

The most difficult part of this is determining what field of study will, in fact, be one where you are relatively good compared to others in that field. The only way to discover this is to try a range of possible fields and see where you do well. The first two years of college should normally be such a time of exploration, where you take courses in a range of subjects and see where you excel and where you struggle. You will also see what you enjoy and what you do not. And one should not be surprised if you end up choosing a field you had not expected. Personally, none of my friends in college ended up majoring in the field they thought they would when starting out as a freshman, and nor did I. There is absolutely nothing wrong with this.

The difficult part is recognizing where one can in fact perform near the top of those in the field and where you are fooling yourself. Numerous studies have shown that people typically overestimate their skills relative to others. For example, a now classic study from 1981 found that 93% of Americans in a sample believed they were more skillful car drivers than the median driver, and 88% were safer drivers. Of course, only 50% can be more skillful, or safer, than the median. The study has more recently (in 2023) been replicated, while a meta-study from 2019 confirmed the general problem: Most of us feel we are better-than-the-average in many domains.

So how can we keep from fooling ourselves? While not easy, the grades received in the range of courses taken when in the exploration stage of college should be an indication. But for this, one needs to take challenging courses and not simply those where one can get a high grade without much in terms of effort or performance. It also requires professors willing and able to provide grades that are true indicators of performance, and not simply uniformly high grades to everyone as the easy path to follow. While it may not feel like it at the time, the most valuable gift one can receive is to get a poor grade in a field you are considering to major in but in which you in fact are not performing all that well. It is far better to discover this when in college, rather than years later in a career in a field that you are not all that good at.

That is also why one should not pay much attention to an overall grade point average. While grades in your senior year can demonstrate whether you have mastered the field, grades as a freshman or sophomore should reflect experimentation over a range of subject areas in those years, where some of those grades may be good and some not-so-good.

College should be a time of discovery – a time when you can explore many different fields and find out where you can in fact do well and where not. It should be a time when you receive what I would term a true “education” by mastering in depth some particular field of study. By the time of graduation one should have learned “how to think like a _____ ” (with the blank filled in based on the specific field). That is, have you developed a deep and thorough understanding of the field? Or have you basically only memorized some of its findings or conclusions, without a good understanding of how they were reached? A career can be built on the former, but the latter soon dissipates.

=======================

Note on the Data:

The data for the charts come ultimately from the American Community Survey (ACS) of the US Census Bureau. The ACS is an annual survey (with the most recently released data from 2022) based on a very large sample of about 2 million households interviewed each year. While the Census Bureau provides easy access to tables based on the ACS for average figures, to obtain the full distribution of earnings – such as in the charts above – one needs to extract data from the Public Use Microdata Sample. This provides, for a representative sample of the households surveyed, the full set of responses to the questionnaire at the level of the individual household. One can then extract the wage and salary earnings of those individuals with a Bachelor’s degree who majored in a given field, and from this determine the full distribution of those earnings, not just the average. I included all adults with a Bachelor’s degree at all age levels.

Operationally, I extracted the data via the IPUMS USA website (an institute based at the University of Minnesota – IPUMS is an acronym for “Integrated Public Use Microdata Series”). IPUMS provides easy access to the ACS data through an online data analysis tool so no special statistical analysis software (such as SPSS or SAS) is required (although those are supported as well at the IPUMS site). The IPUMS USA site includes data not only from the most recent ACS survey, but from each of the ACS surveys going back to 2000, and to the decennial US census going all the way back to 1790. In addition, there are separate IPUMS sites for a range of other microdata files, both for the US and internationally.

You must be logged in to post a comment.