An earlier post on this blog (from January 2013, following the horrific shooting at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Connecticut), looked at the impact of the 1994 Federal Assault Weapons Ban on the number of (and number of deaths from) mass shootings during the 10-year period the law was in effect. The data at that point only went through 2012, and with that limited time period one could not draw strong conclusions as to whether the assault weapons ban (with the law as written and implemented) had a major effect. There were fewer mass shootings over most of the years in that 1994 to 2004 period, but 1998 and 1999 were notable exceptions.

There has now been another horrific shooting at a school – this time at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida. There are once again calls to limit access to the military-style semiautomatic assault weapons that have been used in most of these mass shootings (including the ones at Sandy Hook and Stoneman Douglas). And essentially nothing positive had been done following the Sandy Hook shootings. Indeed, a number of states passed laws which made such weapons even more readily available than before. And rather than limiting access to such weapons, the NRA response following Sandy Hook was that armed guards should be posted at every school. There are, indeed, now more armed guards at our schools. Yet an armed guard at Stoneman Douglas did not prevent this tragedy.

With the passage of time, we now have five more years of data than we had at the time of the Sandy Hook shooting. With this additional data, can we now determine with more confidence whether the Assault Weapons Ban had an impact, with fewer shootings incidents and fewer deaths from such shootings?

This post will look at this. With the additional five years of data, it now appears clear that the 1994 to 2004 period did represent a change in the sadly rising trend, with a reduction most clearly in the number of fatalities from and total victims of those mass shootings. This was true even though the 1994 Assault Weapons Ban was a decidedly weak law, with a number of loopholes that allowed continued access to such weapons for those who wished to obtain them. Any new law should address those loopholes, and I will discuss at the end of this post a few such measures so that such a ban would be more meaningful.

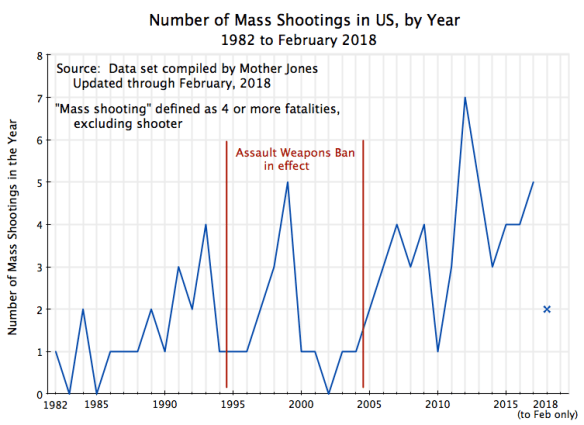

B. The Number of Mass Shootings by Year

The Federal Assault Weapons Ban (formally the “Public Safety and Recreational Firearms Use Protection Act”, and part of a broader crime control bill) was passed by Congress and signed into law on September 13, 1994. The Act banned the sale of any newly manufactured or imported “semiautomatic assault weapon” (as defined by the Act), as well as of newly manufactured or imported large capacity magazines (holding more than 10 rounds of ammunition). The Act had a sunset provision where it would be in effect for ten years, after which it could be modified or extended.

However, it was a weak ban, with many loopholes. First of all, there was a grandfather clause that allowed manufacturers and others to sell all of their existing inventory. Not surprisingly, manufacturers scaled up production sharply while the ban was being debated, as those inventories could later then be sold, and were. Second and related to this, there was no constraint on shops or individuals on the sale of weapons that had been manufactured before the start date, provided just that they were legally owned at the time the law went into effect. Third, “semiautomatic assault weapons” (which included handguns and certain shotguns, in addition to rifles such as the AR-15) were defined quite precisely in the Act. But with that precision, gun manufacturers could make what were essentially cosmetic changes, with the new weapons then not subject to the Act. And fourth, with the sunset provision after 10 years (i.e. to September 12, 2004), the Republican-controlled Congress of 2004 (and President George W. Bush) simply could allow the Act to expire, with nothing done to replace it. And they did.

The ban was therefore weak. But it is still of interest to see whether even such a weak law might have had an impact on the number of, and severity of, mass shootings during the period it was in effect.

The data used for this analysis were assembled by Mother Jones, the investigative newsmagazine and website. The data are available for download in spreadsheet form, and is the most thorough and comprehensive such dataset publicly available. Sadly, the US government has not assembled and made available anything similar. A line in the Mother Jones spreadsheet is provided for each mass shooting incident in the US since 1982, with copious information on each incident (as could be gathered from contemporaneous news reports) including the weapons used when reported. I would encourage readers to browse through the spreadsheet to get a sense of mass shootings in America, the details of which are all too often soon forgotten. My analysis here is based on various calculations one can then derive from this raw data.

This dataset (through 2012) was used in my earlier blog post on the impact of the Assault Weapons Ban, and has now been updated with shootings through February 2018 (as I write this). To be included, a mass shooting incident was defined by Mother Jones as a shooting in a public location (and so excluded incidents such as in a private home, which are normally domestic violence incidents), or in the context of a conventional crime (such as an armed robbery, or from gang violence), and where at least four people were killed (other than the killer himself if he also died, and note it is almost always a he). While other possible definitions of what constitutes a “mass shooting” could be used, Mother Jones argues (and I would agree) that this definition captures well what most people would consider a “mass shooting”. It only constitutes a small subset of all those killed by guns each year, but it is a particularly horrific set.

There was, however, one modification in the updated file, which I adjusted for. Up through 2012, the definition was as above and included all incidents where four or more people died (other than the killer). In 2013, the federal government started to refer to mass shootings as those events where three or more people were killed (other than the killer), and Mother Jones adopted this new criterion for the mass shootings it recorded for 2013 and later. But this added a number of incidents that would not have been included under the earlier criterion (of four or more killed), and would bias any analysis of the trend. Hence I excluded those cases in the charts shown here. Including incidents with exactly three killed would have added no additional cases in 2013, but one additional in 2014, three additional in 2015, two additional in 2016, and six additional in 2017 (and none through end-February in 2018). There would have been a total of 36 additional fatalities (three for each of the 12 additional cases), and 80 additional victims (killed and wounded).

What, then, was the impact of the assault weapons ban? We will first look at this graphically, as trends are often best seen by eye, and then take a look at some of the numbers, as they can provide better precision.

The chart at the top of this post shows the number of mass shooting events each year from 1982 through 2017, plus for the events so far in 2018 (through end-February). The numbers were low through the 1980s (zero, one, or two a year), but then rose. The number of incidents per year was then generally less during the period the Assault Weapons Ban was in effect, but with the notable exceptions of 1998 (three incidents) and especially 1999 (five). The Columbine High School shooting was in 1999, when 13 died and 24 were wounded.

The number of mass shootings then rose in the years after the ban was allowed to expire. This was not yet fully clear when one only had data through 2012, but the more recent data shows that the trend is, sadly, clearly upward. The data suggest that the number of mass shooting incidents were low in the 1980s but then began to rise in the early 1990s; that there was then some fallback during the decade the Assault Weapons Ban was in effect (with 1998 and 1999 as exceptions); but with the lifting of the ban the number of mass shooting incidents began to grow again. (For those statistically minded, a simple linear regression for the full 1982 to 2017 period indicates an upward trend with a t-statistic of a highly significant 4.6 – any t-statistic of greater than 2.0 is generally taken to be statistically significant.)

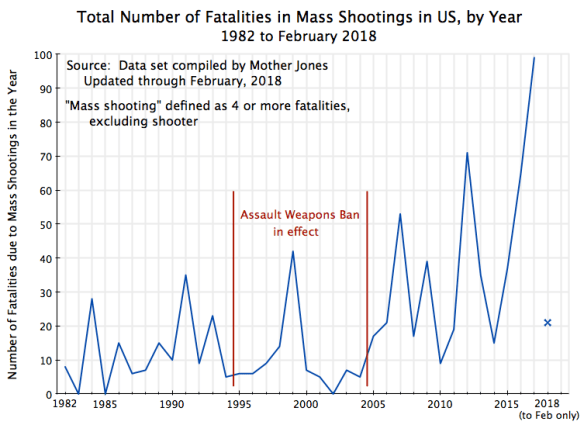

C. The Number of Fatalities and Number of Victims in Mass Shooting Incidents

These trends are even more clear when one examines what happened to the total number of those killed each year, and the total number of victims (killed and wounded).

First, a chart of fatalities from mass shootings over time shows:

Fatalities fluctuated within a relatively narrow band prior to 1994, but then, with the notable exception of 1999, fell while the Assault Weapons Ban was in effect. And they rose sharply after the ban was allowed to expire. There is still a great deal of year to year variation, but the increase over the last decade is clear.

And for the total number of victims:

One again sees a significant reduction during the period the Assault Weapons Ban was in effect (with again the notable exception of 1999, and now 1998 as well). The number of victims then rose in most years following the end of the ban, and went off the charts in 2017. This was due largely to the Las Vegas shooting in October, 2017, where there were 604 victims of the shooter. But even excluding the Las Vegas case, there were still 77 victims in mass shooting events in 2017, more than in any year prior to 2007 (other than 1999).

D. The Results in Tables

One can also calculate the averages per year for the pre-ban period (13 years, from 1982 to 1994), the period of the ban (September 1994 to September 2004), and then for the post-ban period (again 13 years, from 2005 to 2017):

Number of Mass Shootings and Their Victims – Averages per Year

|

Avg per Year |

Shootings |

Fatalities |

Injured |

Total Victims |

|

1982-1994 |

1.5 |

12.4 |

14.2 |

26.6 |

|

1995-2004 |

1.5 |

9.6 |

10.1 |

19.7 |

|

2005-2017 |

3.8 |

38.6 |

71.5 |

110.2 |

Note: One shooting in December 2004 (following the lifting of the Assault Weapons Ban in September 2004) is combined here with the 2005 numbers. And the single shooting in 1994 was in June, before the ban went into effect in September.

The average number of fatalities per year, as well as the number injured and hence the total number of victims, all fell during the period of the ban. They all then jumped sharply once the ban was lifted. While one should acknowledge that these are all correlations in time, where much else was also going on, these results are consistent with the ban having a positive effect on reducing the number killed or wounded in such mass shootings.

The number of mass shootings events per year also stabilized during the period the ban was in effect (at an average of 1.5 per year). That is, while the number of mass shooting events was the same (per year) as before, their lethality was less. Plus the number of mass shooting events did level off, and fell back if one compares it to the previous half-decade rather than the previous 13 year period. They had been following a rising trend before. And the number of mass shootings then jumped sharply after the ban was lifted.

The data also allow us to calculate the average number of victims per mass shooting event, broken down by the type of weapon used:

Average Number of Victims per Mass Shooting, by Weapon Used

|

Number of Shootings |

Fatalities |

Injured |

Total Victims |

|

|

Semiauto Rifle Used |

26 |

13.0 |

34.6 |

47.6 |

|

Semiauto Rifle Not Used |

59 |

7.5 |

5.6 |

13.1 |

|

Semiauto Handgun Used |

63 |

10.0 |

17.5 |

27.5 |

|

Semiauto Handgun (but Not Semiautomatic Rifle) Used |

48 |

7.7 |

6.0 |

13.7 |

|

No Semiauto Weapon Used |

11 |

6.6 |

4.0 |

10.6 |

There were 26 cases where the dataset Mother Jones assembled allowed one to identify specifically that a semiautomatic rifle was used. (Some news reports were not clear, saying only that a rifle was used. Such cases were not counted here.) This was out of a total of 85 mass shooting events where four or more were killed. But the use of semiautomatic rifles proved to be especially deadly. On average, there were 13 fatalities per mass shooting when one could positively identify that a semiautomatic rifle was used, versus 7.5 per shooting when it was not. And there were close to 48 total victims per mass shooting on average when a semiautomatic rifle was used, versus 13 per shooting when it was not.

The figures when a semiautomatic handgun was used (from what could be identified in the news reports) are very roughly about half-way between these two. But note that there is a great deal of overlap between mass shootings where a semiautomatic handgun was used and where a semiautomatic rifle was also used. Mass shooters typically take multiple weapons with them as they plan out their attacks, including semiautomatic handguns along with their semiautomatic rifles. The fourth line in the table shows the figures when a semiautomatic handgun was used but not also a semiautomatic rifle. These figures are similar to the averages in all of the cases where a semiautomatic rifle was not used (the second line in the table).

The fewest number of fatalities and injured are, however, when no semiautomatic weapons are used at all. Unfortunately, in only 11 of the 85 mass shootings (13%) were neither a semiautomatic rifle nor a semiautomatic handgun used. And these 11 might include a few cases where the news reports did not permit a positive identification that a semiautomatic weapon had been used.

E. What Would Be Needed for a Meaningful Ban

It thus appears that the 1994 Assault Weapons Ban, as weak as it was, had a positive effect on saving lives. But as noted before, it was flawed, with a number of loopholes which meant that the “ban” was far from a true ban. Some of these might have been oversights, or issues only learned with experience, but I suspect most reflected compromises that were necessary to get anything approved by Congress. That will certainly remain an issue.

But if one were to draft a law addressing these issues, what are some of the measures one would include? I will make a few suggestions here, but this list should not be viewed as anything close to comprehensive:

a) First, there should not be a 10-year (or any period) sunset provision. A future Congress could amend the law, or even revoke it, as with any legislation, but this would then require specific action by that future Congress. But with a sunset provision, it is easy simply to do nothing, as the Republican-controlled Congress did in 2004.

b) Second, with hindsight one can see that the 1994 law made a mistake by defining precisely what was considered a “semiautomatic” weapon. This made it possible for manufacturers later to make what were essentially cosmetic changes to the weapons, and then make and sell them. Rather, a semiautomatic weapon should be defined in any such law by its essential feature, which is that one can fire such a weapon repeatedly simply by pulling the trigger once for each shot, with the weapon loading itself.

c) Third, fully automatic weapons (those which fire continuously as long as the trigger is pulled) have been banned since 1986 (if manufactured after May 19, 1986, the day President Reagan signed this into law). But “bump stocks” have not been banned. Bump stocks are devices that effectively convert a semiautomatic weapon into a fully automatic one. Following the horrific shooting in Las Vegas on October 1, 2017, in which 58 were killed and 546 injured, and where the shooter used a bump stock to convert his semiautomatic rifles (he had many) into what were effectively fully automatic weapons, there have been calls for bump stocks to be banned. This should be done, and indeed it is now being recognized that a change in existing law is not even necessary. Attorney General Jeff Sessions said on February 27 that the Department of Justice is re-examining the issue, and implied that there would “soon” be an announcement by the department of regulations that recognize that a semiautomatic weapon equipped with a bump stock meets the definition of a fully automatic weapon.

d) Fourth, a major problem with the 1994 Assault Weapons Ban, as drafted, was it only banned the sale of newly manufactured (or imported) semiautomatic weapons from the date the act was signed into law – September 13, 1994. Manufacturers and shops could sell legally any such weapons produced before then. Not surprisingly, manufacturers ramped up production (and imports) sharply in the months the Act was being debated in Congress, which provided then an ample supply for a substantial period after the law technically went into effect.

But one could set an earlier date of effectiveness, with the ban covering weapons manufactured or imported from that earlier date. This is commonly done in tax law. That is, tax laws being debated during some year will often be made effective for transactions starting from the beginning of the year, or from when the new laws were first proposed, so as not to induce negative actions designed to circumvent the purpose of the new law.

e) Fifth, the 1994 Assault Weapons Ban allowed the sale to the public of any weapons legally owned before the law went into effect on September 13, 1994 (including all those in inventory). This is related to, but different from, the issue discussed immediately above. The issue here is that all such weapons, including those manufactured many years before, could then be sold and resold for as long as those weapons existed. This could continue for decades. And with millions of such weapons now in the US, it would be many decades before the supply of such weapons would be effectively reduced.

To accelerate this, one could instead create a government-funded program to purchase (and then destroy) any such weapons that the seller wished to dispose of. And one would couple this with a ban on the sale of any such weapons to anyone other than the government. There could be no valid legal objection to this as any sales would be voluntary (although I have no doubt the NRA would object), and would be consistent with the ban on the sale of any newly manufactured semiautomatic weapon. One would also couple this with the government buying the weapons at a generous price – say the original price paid for the weapon (or the list price it then had), without any reduction for depreciation.

Semiautomatic weapons are expensive. An assault rifle such as the AR-15 can easily cost $1,000. And one would expect that as those with such weapons in their households grow older and more mature over time, many will recognize that such a weapon does not provide security. Rather, numerous studies have shown (see, for example, here, here, here, and here) that those most likely to be harmed by weapons in a household are either the owners themselves or their loved ones. As the gun owners mature, many are likely to see the danger in keeping such weapons at home, and the attractiveness of disposing of them legally at a good price. Over time, this could lead to a substantial reduction in the type of weapons which have been used in so many of the mass shootings.

F. Conclusion

Semiautomatic weapons are of no use in a civilian setting other than to massacre innocent people. They are of no use in self-defense: One does not walk down the street, or while shopping in the aisles of a Walmart or a Safeway, with an AR-15 strapped to your back. One does not open the front door to your house each time the doorbell rings aiming an AR-15 at whoever is there. Nor are such weapons of any use in hunting. First, they are not terribly accurate. And second, if one succeeded in hitting the animal with multiple shots, all one would have is a bloody mess.

Such weapons are used in the military precisely because they are good at killing people. But for precisely the same reason as fully automatic weapons have been banned since 1986 (and tightly regulated since 1934), semiautomatic weapons should be similarly banned.

The 1994 Assault Weapons Ban sought to do this. However, it was allowed to expire in 2004. It also had numerous loopholes which lessened the effectiveness it could have had. Despite this, the number of those killed and injured in mass shootings fell back substantially while that law was in effect, and then jumped after it expired. And the number of mass shooting events per year leveled off or fell while it was in effect (depending on the period it is being compared to), and then also jumped once it expired.

There are, however, a number of ways a new law banning such weapons could be written to close off those loopholes. A partial list is discussed above. I fully recognize, however, that the likelihood of such a law passing in the current political environment, where Republicans control both the Senate and the House as well as the presidency, are close to nil. One can hope that at some point in the future the political environment will change to the point where an effective ban on semiautomatic weapons can be passed. After all, President Reagan, the hero of Republican conservatives, did sign into law the 1986 act that banned fully automatic weapons. Sadly, I expect many more school children will die from such shootings before this will happen.

You must be logged in to post a comment.