A. Introduction

Climate change is arguably the most important challenge facing the world today. The damage being done by a warming world is already clear: Extreme temperatures have become more common, and extreme weather events have become both more frequent and more severe. Glaciers as well as the ice that used to cover the Artic Ocean are melting, as are the vast ice sheets covering Greenland and Antarctica. And the melting glaciers and ice sheets, as well as thermal expansion as ocean water becomes warmer, are together leading the sea level to rise. If this is not addressed, not only will coastal land be lost but our coastal cities will be inundated.

The problems will grow worse as long as greenhouse gases (mainly carbon dioxide – CO2 – but others as well) continue to be released into the air. The gases accumulate in the atmosphere, with some, such as CO2, lasting for hundreds of years before being diminished by natural processes. It is the cumulative total that matters as it is the concentrations of these gases in the atmosphere that lead to the higher temperatures. And the damage increases more than proportionally with those higher temperatures, where the damage in going from, say, 2 degrees to 3 degrees above the pre-industrial average is far greater than in going from 1 degree to 2 degrees. Global average surface temperatures are already about 1.2 degrees Celsius greater than what they were on average between 1850 and 1900.

There is, however, a good deal of confusion on the basic economics of what will be needed to address this. One hears, for example, politicians and others saying that “we cannot afford” to address climate change. But they have not recognized that the cost of not cutting back on greenhouse gas emissions can be far greater than the cost of reducing those emissions. Indeed, the cost of reducing greenhouse gas emissions is actually often quite low, even though the cost of not addressing climate change is high. Those two concepts are different but are sometimes not clearly distinguished.

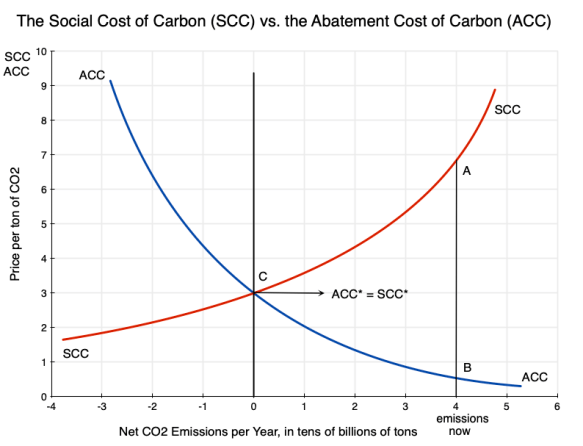

A diagram such as that at the top of this post can be helpful in keeping the concepts clear, as well as in understanding how they interact. Many might immediately note the similarity to the standard supply and demand diagrams that economists (but few others) know and love, and there is indeed a similarity. But there is an important difference: In the supply and demand diagrams normally used, what is being produced and made available is something good, and hence one wants more of it. But in the diagrams here, what is being produced (polluting greenhouse gases, and in particular CO2 as the primary greenhouse gas) is something bad. Hence one wants less of it. But it costs something to reduce those emissions.

The first section below will discuss this diagram, including the concepts behind it and how to interpret and use it to examine various issues. This will all be just standard economics, but for something one wants less of rather than more of. The basic measures – analogous to a demand price and a supply price – are the Social Cost of Carbon (SCC – what it costs society when an extra unit of CO2 is emitted) and what I have labeled here the Abatement Cost of Carbon (ACC- what it costs to reduce the emissions of CO2 by a unit).

The post will then discuss some of the implications that one can work out from this simple diagram. One does not need to know precisely where those curves will be – just their basic relationship to each other. And a fair amount can be found simply from the concepts themselves. The key is to be clear as one thinks things through. How one in practice determines estimates of specific values for the SCC and the ACC is also important, of course, but that issue is different and will be reviewed in subsequent posts on this blog. There is an enormous literature on determining those values, a fair amount of controversy, and as practitioners always emphasize, also a good deal of uncertainty. But there is much that follows from the basic concepts themselves, and this blog post will focus on that.

One point of disclosure: The diagram above was derived from first principles. And it is a diagram that I thought would be fairly commonly seen in the literature on climate change. However, while I looked for references using it, I could not find any. This does not mean that no one has ever produced something similar. Someone almost certainly has. But I have not been able to find an example. At a minimum, it does not appear to be common, and thus reviewing the basic concepts here may be of interest.

July 25, 2023 – Update: A reader of this blog flagged to me that there is indeed a text that presents a diagram very similar to what I discuss here. The text is “Principles of Environmental Economics: Economics, Ecology, and Public Policy”, by Ahmed M. Hussen (a professor of economics at Kalamazoo College in Michigan, USA). I would like to thank Mr. Naren Mistry for bringing this reference to my attention.

Furthermore, I created the term “Abatement Cost of Carbon” used here – the cost to reduce the emissions of CO2 by a unit. I believe it is a good description of the concept, but as will be discussed in the subsequent post on estimating the ACC, others have examined somewhat similar concepts with various names.

B. The Social Cost of Carbon vs. the Abatement Cost of Carbon

The diagram at the top of this post presents schematically the relationship between the Social Cost of Carbon (SCC) and the Abatement Cost of Carbon (ACC). These are drawn in relation to the net number of tons of CO2 emissions per year along the horizontal axis of the chart (or x-axis). And while the diagram is shown in terms of CO2 emissions, CO2 is being taken as a proxy for all greenhouse gas emissions (which are often expressed in CO2 equivalent terms – equivalent in terms of their global warming impact over a period that is usually taken to be 100 years).

While one could measure the CO2 in any physical unit, I have labeled it as tens of billions of tons per year. World emissions in 2021 were about 37 billion metric tons. But the physical units one can use are arbitrary. I also want to make clear that while the horizontal axis depicts CO2 emissions as so many tons (or tens of billions of tons) per year, this is simply a representation of the scale of production of those emissions per year. The price (whether SCC or ACC) is then of one unit (one ton) of those CO2 emissions in any given year – not a price of one ton being emitted each year for multiple years. It is the price for just one ton, once.

The Social Cost of Carbon (SCC) is the cost to society of a unit of CO2 being emitted into the atmosphere today, in a scenario where CO2 emissions overall are at the pace per year shown on the horizontal axis. One can think of the SCC as what society would be willing to pay to avoid a unit of CO2 being released into the air. Since CO2 will remain in the atmosphere for hundreds of years, the damage due to its incremental global warming effect will equal the damage this year, plus the damage next year, plus the year after that, and so on for hundreds of years.

These future damages will be discounted back to the present year based on some social discount rate. The subsequent blog post on how the SCC is estimated, referred to above, discusses the question of what the appropriate social discount rate should be. It will have a significant impact on the specific value of the SCC estimated, and is an issue that has been much debated. For now we will simply assume that a suitable social discount rate has been used. But an important and practical implication of discounting is that what matters most in the determination of the SCC estimate will only be the damages over the next century or so. Beyond that, the discounted values are generally so small (depending on the specific social discount rate used) as not to materially affect the SCC estimate.

The damages caused by an extra unit of CO2 being emitted today will depend on how much CO2 (and other greenhouse gases) are already in the atmosphere. Importantly, the resulting economic damage (which the SCC measures) per unit of global temperature increase will be highly non-linear. As noted above, the incremental extra damages will be greater if the CO2 (and other greenhouse gases) have led global average temperatures to be, say 2 degrees higher than what they were in the pre-industrial era, than what the incremental damages were when those temperatures were 1 degree higher. And those per unit damages will be greater still when coming on top of concentrations that would have led to temperatures 3 degrees higher (than in the pre-industrial period) compared to the incremental impact at 2 degrees higher.

In addition, and also importantly, there are feedback effects resulting from increasing concentrations of CO2 in the air that also lead to more than proportionally higher global temperatures. An important example is the effect on permafrost. A higher global temperature leads to permafrost that is on the margin of remaining frozen, instead to melt. And melted permafrost then leads to additional greenhouse gases being released into the air (in particular the highly potent greenhouse gas methane), which then leads to even higher global temperatures.

For both of these reasons (the resulting economic damages, and the feedback effects) the SCC curve in the diagram above not only slopes upward but also bends upwards.

There is one shortcoming in such a schematic, however, that should be flagged. Supply and demand diagrams are static and do not handle the time dimension well. There are similar issues here. In particular, as emissions accumulate in the atmosphere over time, the damages will be greater. The SCC curve as shown (over its full length) can be viewed as what it would be for a given starting point for the concentration of CO2 in the air. At higher atmospheric concentrations of CO2, it will shift upwards over its entire length. This could in principle be handled by adding a third dimension to the diagram. That is, one could add a third axis perpendicular to the other two (and going away – i.e. adding depth) for the stock of CO2 that had accumulated in the atmosphere. The two-dimensional diagram shown here can then be thought of as a slice of that more complete three-dimensional chart – showing a slice for some given level of accumulated CO2. But such a three-dimensional diagram would be complicated, and the two-dimensional one is adequate for our purposes here.

The Abatement Cost of Carbon (ACC) is what it would cost society to reduce the emissions of CO2 by one unit. When emissions are high (the right side of the chart), it does not cost much to reduce those emissions by a unit. There are a lot of relatively easy (low-cost) things that one can do. But as emissions are reduced, ultimately to zero and then even into net negative levels, it becomes increasingly difficult (and hence increasingly costly) to reduce them further. Hence the ACC curve goes from the upper left in the diagram to the lower right, and bends upwards as well.

The resulting SCC and ACC curves should therefore be expected to look like those shown. The SCC curve starts high on the right side of the chart (as damages are great when CO2 emissions are high and assumed to remain so); they fall as one moves to the left to lower rates of emissions (with a resulting lower pace of CO2 being released into the air); and the curve bends upward. The ACC curve, in contrast, starts low on the right – when a high rate of emissions means much could be done at a low cost to reduce those emissions by a unit – and then rises as one moves to the left to lower rates of emissions and it becomes increasingly more difficult (more costly) to reduce emissions by an additional unit. It will also bend upwards.

At some point the ACC and SCC curves will cross. In the diagram above, I have them cross at net emissions of zero. The reason for that will be discussed below. But there is no a priori reason why they should necessarily cross at zero net emissions. Where they will cross is an empirical issue. Rather, all one knows is that they will cross at some point. (A contrarian might note that it is possible that the ACC curve might theoretically lie always and everywhere above the SCC curve – at least within the range of CO2 emissions shown on the diagram – and hence will never cross it. But any reasonable estimate of the SCC and the ACC finds that that is not nearly the case in practice – and not by orders of magnitude.)

C. Some Implications

With these basics, one can draw several implications of interest:

a) First, at current levels of CO2 emissions (well to the right in the diagram), the SCC will be high and ACC will be low. In the diagram at the top of this post, the SCC at point A is far above the ACC at point B. To say that “we cannot afford” to reduce emissions of CO2 is simply wrong as the cost of not taking action to reduce emissions (the SCC at current emission rates) is well above what it would cost to reduce carbon emissions from their current pace (the ACC at current emission rates). Indeed, the opposite is closer to the truth: We cannot afford not taking action to reduce CO2 emissions. And it will remain worthwhile to do this as long as the SCC is above the ACC.

b) The SCC curve will intersect the ACC curve at some point. At the point where they intersect the cost of reducing CO2 emissions by a further unit (the ACC) will match the benefit of doing so (the SCC, i.e. the cost to society from a unit of CO2 being emitted). Beyond that (i.e. further to the left), the cost of further reducing CO2 emissions exceeds the benefits. At the point where they intersect, the benefits will match the costs.

In the diagram, I have drawn the curves so that they cross at zero net emissions of CO2. This is the “net zero” goal that the international community has targeted as the appropriate goal to address climate change. Assuming the international community is acting fully rationally (a big stretch, I acknowledge), then that net zero goal is the appropriate one if the SCC and ACC curves cross at that point. I have assumed that in the diagram, and the point where they cross is labeled as point C in the diagram, with ACC* = SCC* there.

c) In reality, there is of course a good deal of uncertainty on where the SCC and ACC curves lie, and hence where they cross. But they do cross somewhere, and as we learn over time more about how the climate is changing, about the costs that the changing climate is imposing on the world, and what it would cost to cut back on CO2 emissions, we will become better able to determine where that intersection is. But we do not need to know that with any precision right now. All we need to know at the current moment is that the point where they cross is at a level of CO2 emissions that are well below where they now are, and that therefore we should be reducing CO2 emissions (i.e. moving to the left in the diagram).

d) But the fact that the SCC is something positive even at net zero emissions brings out that even at net zero emissions – whenever that is achieved – there will still be damage being done from the CO2 that has accumulated in the atmosphere up to that point. The planet would be as hot as it had ever been, with all the resulting consequences for the climate. It would just not be getting even hotter (setting aside the complicated lags in the climate system – an important but separate issue).

e) There would therefore be benefits from reducing the accumulated CO2 in the air from where it would be at that point, even if net emissions at that point were zero. There is nothing special about net zero as a target – other than the ease with which it can be explained politically. If it is the case that the cost of reducing CO2 emissions further at that point (the ACC curve) is below what the cost from damages would be of one more unit of CO2 in the air (the SCC curve), then it would make sense to reduce the net emissions of CO2 further.

It might well become significantly more difficult (more costly) to reduce CO2 emissions further once one has reached the net zero level. It is easier to stop putting more CO2 into the air than it is to draw CO2 out of the air. But there are ways to do this. One can plant more trees, for example, or adopt agricultural practices that fix more carbon in the soil or in the oceans, or make use of more esoteric (and currently much more expensive) technologies that draw CO2 directly out from the air and then store it some manner where it will not end up in the air again. But the fundamental point to recognize is that there is nothing that special about net zero emissions. Depending on the cost (the ACC), one might well want to take action to reduce some of the CO2 we have put into the air.

f) This brings us to the role of technology and how, over time, one should expect the technologies for reducing carbon emissions to continue to improve and thus continue to reduce the cost of abating carbon emissions. The impact of such technological change in reducing the cost of abatement of emissions would be to shift the ACC curve downward, as shown here:

The appropriate goal would then be to reduce net CO2 emissions even further to the left, into the net negative levels at point D in the diagram rather than point C. With the technology assumed to be available by the time society has reduced CO2 emissions to point C, the cost to reduce it further could by then be less. At point C, the SCC cost shown in the diagram would be 3 (in some monetary units – dollars or euros or yen or whatever – per some given physical unit), but the ACC cost to reduce CO2 by one of those physical units would be less at a bit below 2 in this diagram. Thus it would make sense to reduce CO2 emissions even further (into negative levels), where at D one would be matching the cost to society from it (the SCC) with the cost of reducing it making use of the technology available then (on the ACC’ curve).

D. Summary and Conclusion

That there is a distinction between the costs that carbon emissions impose on society (the SCC) and what it would cost to reduce those emissions (the ACC) is obvious as soon as one thinks about it. But many people – and especially politicians – often do not think about it, and have confused the two.

One can look at the issue with the simple tools of basic economics. The only difference with what is normally done is that what is being produced here (CO2 emissions) are something bad – and hence one wants less of them – rather than something good. And it costs something to reduce those CO2 emissions, even though there is a benefit when they are reduced. This is in contrast to standard goods, where it costs something to produce more of them and there is a benefit when one has more of them.

Seen in this way, the SCC can be viewed as similar to but with an opposite sign to a demand price. A demand price is what one would pay to obtain something good, while the SCC is a measure of the benefit one would obtain (what one would be willing to pay) in order to reduce CO2 emissions by a unit. And while a standard supply price is how much it would cost to increase production by a unit, the ACC is how much it would cost to reduce emissions by a unit.

This then yields a simple diagram such as that at the top of this post, but where instead of a downward-sloping demand curve and an upward-sloping supply curve (as in a standard supply-demand diagram for a normal good – a good that one wants more of), the analog to the demand curve (the SCC curve) slopes up rather than down and the analog to the supply curve (the ACC) slopes down rather than up (all in going from left to right).

Several implications then follow. The world is currently emitting high levels of CO2, and should that pace of emissions continue, the costs to society from climate change will be immense. That is, the SCC is high. But at these levels of CO2 emissions, there is a lot that can be done, at a low cost, to reduce those emissions by a unit. That is, the ACC is low. It is therefore mistaken to assert “we cannot afford” to reduce CO2 emissions. The cost to society from not reducing them will be far greater.

The pace of CO2 emissions should then be reduced as long as the costs to society from releasing these greenhouse gases into the air (the SCC) exceeds the cost of reducing such emissions (the ACC). At some point the curves will cross, and at that point it would no longer be worthwhile to reduce further the CO2 going into the air. The now broadly accepted goal of the international community that net emissions of CO2 should go to zero would be logical if the SCC and ACC curves cross at net zero emissions (and I have drawn the diagram at the top of this post as if this is the case). But there is uncertainty on precisely where those curves lie. And it is indeed possible they cross at a net negative pace of emissions – i.e. where CO2 would be removed from the atmosphere by some means. It is also likely that as technology improves, the position where they cross will move further to the left.

But there is no need to know today precisely where they might cross. All we need to know right now is that with the social costs from emitting CO2 (the SCC) far in excess of what it would cost to reduce those emissions (the ACC), we should be reducing the CO2 we are putting into the air each year. Progress on this will take time, but as CO2 emissions are reduced we will learn more about what the true costs are: for the SCC as well as the ACC. And with technology also advancing, it may well be the case that society will benefit not simply from reducing net emissions to zero, but then in moving beyond that – and possibly well beyond that – to removing CO2 from the atmosphere.

But that is something that we do not need to address today. As the common saying goes, if you are digging yourself into a hole, the first thing to do is to stop digging. That is, stop emitting the greenhouse gases that are warming the planet. But once we have stopped digging the hole even deeper, there will be the issue of how far out of that hole we should want to go.

This post has covered only the basics. The practical question remains of how one estimates what the SCC and ACC figures are. That will come in subsequent posts that I hope to put up soon.

You must be logged in to post a comment.