Larry Summers published an op-ed yesterday (appearing in Reuters, the Financial Times, the Washington Post, and probably elsewhere) in which he makes the important point that the current budget impasse is focussed on the wrong issues. The discussion, at least as publicly expressed, has focussed on what is seen as needed to deal with the fiscal deficit and the resulting public debt. Even the Republican attempt to end ObamaCare was ostensibly about cutting the government deficit (even though the CBO concluded that the opposite would happen, as they found that the ObamaCare reforms will reduce the deficit, rather than increase it).

Yet this focus on near term and projected budget deficits is misguided. As Summers notes, under current policies the public debt to GDP ratio is falling, and is projected to continue to fall into the 2020s. The recently issued Long-Term CBO budget projections indicate that while the debt ratio would then start to rise (primarily driven by expected higher health care costs), there is a good deal of uncertainty in those projections.

Specifically the CBO figures show that it would not take much, in terms of either higher revenues or lower spending, to keep the public debt to GDP ratio flat. Higher revenues or lower spending or some combination of the two, of 0.8% of GDP over the next 25 years or 1.7% of GDP over the next 75 years, would suffice. This is consistent with an earlier post on this blog, which showed that if the Bush tax cuts had not been extended for almost all households, the projected debt to GDP ratio in the CBO numbers would fall rapidly.

But projections of revenues or of spending are highly uncertain. Projected health care spending has been coming down steadily in recent years, for example, in part due to the slow economy, but also in part as a result of the efficiency gains and cost reductions that the ObamaCare reforms are leading to. With these lower costs, the CBO has been steadily reducing the projected costs to the government budget from Medicare, Medicaid, and other such health programs. In the recent CBO report, for example, the projections of government spending on health care programs in the 2030s were reduced by 0.5% of GDP from what the CBO had projected just one year earlier. Going back further, the CBO projections for government spending on health care in 2035 were over 1% of GDP lower in the projections recently issued than in the projections published in June 2010.

This should not be interpreted as a criticism of CBO. Their projections are probably the best available. Rather, the point is that these projections are inherently hard to do, and the uncertainty surrounding them should not be ignored. Yet the politicians often ignore precisely that.

Furthermore and perhaps most importantly, the projected budget deficits and resulting public debt to GDP ratios depend critically on the rate of growth of the economy. The CBO uses a fairly detailed and reasonable model to project this (based on projected labor force growth, investment in capital, and productivity growth). However, it is probably even more difficult to project GDP than to project future spending levels and tax revenues for any given level of future GDP. But Summers notes the critical sensitivity of the projected future deficits to the projected growth in GDP. He states “Data from the CBO imply that an increase of just 0.2 percent in annual growth would entirely eliminate the projected long-term budget gap”.

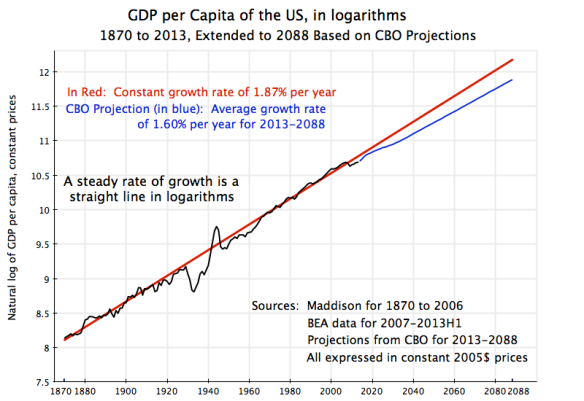

One can calculate from the data made available with the CBO report their projected growth of real per capita GDP. For 2013 to 2088, it comes to 1.60% year. A previous post on this blog noted the remarkable constancy of the rate of growth of real per capita GDP since at least 1870 of 1.9% a year (or 1.87% a year at two digit precision). That earlier post noted that real per capita GDP in the US, despite large annual variations and even decade long deviations (such as during the Great Depression, and then during World War II), has always returned to a path of 1.87% growth since at least 1870. That path even did not shift when there were even substantial deviations, such as during the Great Depression. Rather, the economy always returned to the same, previous, path, and not one shifted up or down.

This is truly remarkable, and no one really knows the reason. The path can be seen as a trend growth of capacity (based on labor available and capital invested, coupled with the technology of the time), but why this should path should have grown at 1.87% a year in the late 1800s; in the early, mid and late 1900s; and all the way into the 21st century, is not known.

Since we do not know why the economy has always returned to this one path, we need to be careful in looking forward. Still, it is noteworthy that the CBO projections imply that the economy will now slow, to just 1.60% real per capita GDP growth over the next 75 years. This CBO path is substantially lower than the path of 1.87% growth that has ruled for the last 140 years in the US.

The graph at the top of this post shows the path of GDP per capita projected by the CBO (which one should note is a year by year projection, which just averages out to 1.60% per year over the full period), along with an extension of the 1.87% path that has ruled since at least the 1870s. The graph is adapted from my earlier post (although now converted to prices of 2005 whereas the earlier one was in prices of 1990; this does not affect the rates of growth). It is expressed in logarithms, since in logarithms a constant rate of growth is a straight line.

It is not clear why there should be this deceleration to 1.60% from the 1.87% rate of growth the economy has followed over the last 140 years. Mechanically, one can ascribe the deceleration to what the CBO assumes for the rate of growth of technological progress. But projecting growth in technology over a 75 year period is basically impossible, as the CBO notes.

The deceleration over the next 75 years has a very important implication, however. The CBO found in its sensitivity analysis that a rate of growth that is just 0.2% faster will suffice to close the budgetary gap, even if one does not take any new measures to raise revenues or cut government spending. Hence a return to the previous historical growth path of 1.87% a year from the 1.60% rate the CBO projects, or a difference of 0.27%, will more than suffice to close the budgetary gap.

The policy implication is that with such sensitivity to the growth in GDP, we should be focussed on measures to raise growth, rather than short term budgetary measures that will act to reduce growth. The economy has suffered from government austerity since 2010, which has held back growth. Government has been cutting spending, thus undermining demand in an economy with high unemployment and close to zero interest rates, where more labor is not employed and more is not produced because the resulting products could not then be sold due to the lack of demand. As an earlier post on this blog noted, if government spending had been allowed to grow simply at the historic average rate (and even more so if it had been allowed to grow as it had under Reagan), the US would by now be back at full employment.

Over the medium term, Summers notes that both conservatives and liberals agree that growth should be raised, and on the types of measures which should help this. More investment, both public and private, is required rather than less. Research and development, both public and private, is important. More effective education is also required.

I would agree with all of these. But to be honest, since we do not really understand why the economy always returned to the 1.87% growth path over the last 140 years, it would not be correct to say we can be sure such measures will be effective. However, what we can say with confidence is that measures that hinder the recovery of the economy, as the government spending cuts have been doing, will certainly hurt.

You must be logged in to post a comment.