A. Introduction

An important issue in the current presidential campaign, although somewhat technical, is whether one should expect that employment could jump to substantially higher levels than where it is now, if only economic policy were better. The argument is that while the unemployment rate as officially measured (4.9% currently) might appear to be relatively low and within the range normally considered “full employment”, this masks that many people (it is asserted) have given up looking for jobs and make up a large reservoir of “hidden unemployed”. If only the economy were functioning better, it is said, more jobs would be created and taken up by these hidden unemployed, the economy would then be producing more, and everyone would be better off.

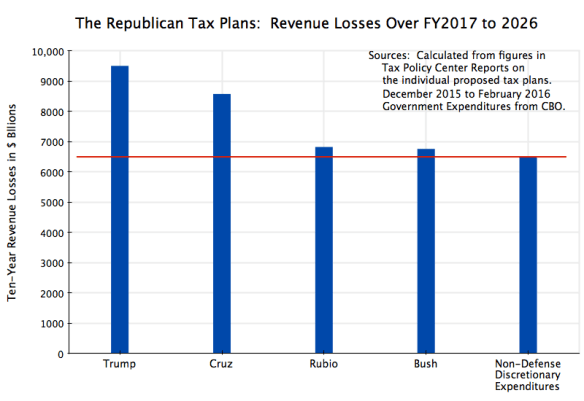

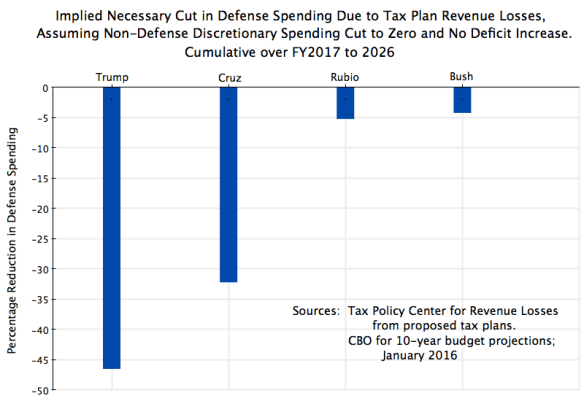

This is important for the Republicans, not only as part of their criticism of Obama, but also as a basis for their tax plans. As discussed in the previous post on this blog, the Republican tax plans would all cut tax rates sharply, leading to such revenue losses that deficits would rise dramatically even if non-defense discretionary budget expenditures were cut all the way to zero. The Republican candidates have asserted that deficits would not rise (even with sharply higher spending for defense, which they also want), because the tax cuts would spur such a large increase in growth of GDP that the tax revenues from the higher output would offset the reductions from lower tax rates. Aside from the fact that there is no evidence to support the theory that such tax cuts would spur growth by any amount, much less the jump they are postulating (see the earlier blog post for a discussion), any rise in GDP of such magnitude would also depend on there being unemployed labor to take on such jobs. With the economy now at close to full employment (with the unemployment rate of 4.9%), this could only be achieved if a large pool of hidden unemployed exists to enter (or re-enter) the labor force.

Given the huge magnitudes involved, few economists see these Republican tax plans as serious. One cannot have such massive tax cuts and expect deficits not to rise. And Democrats have long criticized such Republican plans for being unrealistic (there were similar, although not as extreme, Republican tax plans in the 2012 campaign, and Paul Ryan’s budget plans also relied on completely unrealistic assumptions).

Unfortunately, the Bernie Sanders campaign this year on the Democratic side has similarly set out proposals that are economically unrealistic. A detailed assessment of the Bernie Sanders economic program by Professor Gerald Friedman of the University of Massachusetts at Amherst concluded that the Sanders program would raise GDP growth rates by more than even the Republicans are claiming. But even left-wing commentators have criticized it heavily. Kevin Drum at Mother Jones, for example, said the Sanders campaign had “crossed into neverland”.

A more detailed and technical evaluation from Professors Christina Romer and David Romer of UC Berkeley (with Christina Romer also the first Chair of the Council of Economic Advisers in the Obama Administration), concluded Friedman’s work was “highly deficient”, as they more politely put it. And an open letter issued by four former Chairs of the Council of Economic Advisers under Obama and Bill Clinton (including Christina Romer) said “the economic facts do not support these fantastical claims”.

This is important. In recent decades, it was the Republican candidates who have set out economic programs which did not add up or which depended on completely unrealistic assumptions of how the economy would respond. The analysis by Professor Friedman of the Sanders program is similarly unrealistic. As the four former Chairs of the CEA put it in their open letter:

“As much as we wish it were so, no credible economic research supports economic impacts of these magnitudes. Making such promises runs against our [Democratic] party’s best traditions of evidence-based policy making and undermines our reputation as the party of responsible arithmetic. These claims undermine the credibility of the progressive economic agenda and make it that much more difficult to challenge the unrealistic claims made by Republican candidates.”

To be fair, the relationship of the Friedman work to the Sanders campaign is not fully clear. At least one news report said the analysis was prepared at the request of Sanders, while others said not. But upon its release, the Sanders campaign did explicitly say it was “outstanding work” which should receive more attention. And when the work began to be criticized by economists such as the former chairs of the CEA, the response of the Sanders campaign was that their criticism should be dismissed, as they were of “the establishment of the establishment”. Rather than engage on the real issues raised, the Sanders campaign simply dismissed the criticisms. This does not help.

Both the Republican plans and the Sanders program depend on the assumption that so many workers would enter or re-enter the labor force that GDP could take a quantum leap up from what current projections consider to be possible. (Both depend on other assumptions as well, such as unrealistically high assumptions on what would happen to productivity growth. But it is not the purpose of this blog post to go into all such issues. Rather, it is to address the single issue of labor force participation.) Their plans depend on a higher share of the population participating in the labor force than currently choose to do so, leading to an employment to population ratio that would thus rise sharply. We will look in this post at whether this is possible. An earlier post on this blog examined similar issues. This post will come at it from a slightly different direction, and will update the figures to reflect the most recent numbers.

The key chart will be the one shown at the top of this post. But to get to it, we will first go through a series of charts that set the story. The data all come from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), either directly, or via the data set maintained by the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis (FRED).

B. Recent Behavior of the Employment to Population Ratio

Many observers, from both the left and the right of the political spectrum, have looked at how the employment to population ratio has moved in the recent downturn, and concluded that there must be a significant reservoir of hidden unemployed. Specifically, they have looked at charts such as the following:

Employment as a share of the population fell rapidly and sharply with the onset of the economic downturn in 2008, in the last year of the Bush Administration, and reached a low point in late 2009. From about 63% in 2007 to around 58 1/2% in late 2009, it fell by over 7%. It then remained at such low levels until 2013, rising only slowly, and since then has risen somewhat faster.

But at the current reading of 59.8%, it remains well below the 63% levels of 2007. And it remains even more below the peak it reached in the history of the series of 64.7% in April 2000. If this does, in fact, reflect a pool of hidden unemployed, then GDP could be significantly higher than it is now. Assuming for simplicity that GDP would rise in proportion to the increase in workers employed, annual GDP would be close to a trillion dollars higher if the employment to population ratio rose from the current 59.8% to the 63% that prevailed in 2007. And annual GDP would be close to $1.5 trillion higher if the ratio could revert to where it was in April 2000. With a share of about 25% of this accruing in taxes, this would be a significant pot of money, which could be used for many things.

But is this realistic? The short answer is no. The population has moved on, with important demographic as well as social changes that cannot be ignored.

C. Adding the Labor Force Participation Rate

A problem with the employment to population measure is that people will not be employed not just due to unemployment (are looking but cannot find a job), but also because they might not want to be working at the moment. If older, they might be retired, and happily so. If younger (the figures are for all adults in the civilian population, defined as age 16 or older), they might be students in high school or college. And not all those in middle age will want to be working: Until recent decades, a large share of adult women did not participate in the formal labor force. Women’s participation in the formal labor force has, however, changed significantly over time, and is one of the key factors underlying the rise seen in the overall labor force participation rate over time. Such factors should not be ignored, but are being ignored when one looks solely at the employment to population ratio.

The first step is to take into account unemployment. Unemployment accounts for the difference between the employment to population ratio and the labor force participation rate (which is, stated another way, the labor force to population ratio). Adding the labor force participation rate to the diagram yields:

Note the unemployment rate as traditionally referred to (currently 4.9%) is not the simple difference, in percentage points, between the labor force participation rate (62.9% in February 2016) and the employment to population ratio (59.8% in February 2016). The unemployment rate is traditionally defined as a ratio to the labor force, not to population, while the two measures of labor force participation rate and employment to population ratio are both defined as shares of the population. Note that if you take the difference here (62.9% – 59.8% = 3.1% points in February 2016), and divide it by the labor force participation rate (62.9%), one will get the unemployment rate of 4.9% of the labor force. But all this is just arithmetic.

The key point to note for the chart above is that while the employment to population ratio fell sharply in the 2008-2009 downturn, and then recovered only slowly, the labor force participation rate has been moving fairly steadily downward throughout the period. There is month to month variation for various reasons, including that all these figures are based on surveys of households. There will therefore be statistical noise. But the downward trend over the period is clear. The question is why. Does it perhaps reflect people dropping out of the labor force due to an inability to find jobs when the labor market is slack with high unemployment (the “discouraged worker” effect)? Some commentators have indeed noted that the upward bump seen in the figures in the last few months (since last November), with the unemployment rate now low and hence jobs perhaps easier to find, might reflect this. Or is it something else?

D. The Longer Term Trend

A first step, then, is to step back and look at how the labor force participation rate has moved over a longer period of time. Going back to 1948, when the data series starts:

The series peaked in early 2000, at a rate of 67.3%, and has moved mostly downward since. It was already in 2007 well below where it had been in 2000, and the decline since then continues along largely the same downward path (where the flattening out between 2004 and 2007 was temporary). Prior to 2000, it had risen strongly since the mid-1960s.

One does see some downward deviation from the trend whenever there was an economic downturn, but then that the series soon returned to trend. Thus, for example, the labor force participation rate rose rapidly during the years of Jimmy Carter’s presidency in the late 1970s, but then leveled off in the economic downturn of the early 1980s during the Reagan years. The unemployment rate peaked at 10.8% in late 1982 under Reagan (significantly more than the 10.0% it peaked at in 2009 under Obama), and one can see that the labor force participation rate leveled off in those years rather than continued the rise seen in the years before. But these are relatively mild “bumps” in the broader long-term story of a rise to 2000 and then a fall.

The long term trend has therefore been a fairly consistent rise over the 35 years from the mid-1960s to 2000, and then a fairly consistent fall in the 16 years since then. The question to address next is why has it behaved this way.

E. Taking Account of an Aging Society, Students in School, and Male / Female Differences

As people age, they seek to retire. Normal retirement age in the US has been around age 65, but there is no rigid rule that it has to be at that precisely that age. Some retire a few years earlier and some a few years later. But as one gets older, the share that will be retired (and hence not in the formal labor force) will increase. And with the demographic dynamics where an increasing share of the US population has been getting older over time (due in part to the baby boom generation, but not just that), one would expect the labor force participation rate to decline over time, and especially so in recent years as the baby boom generation has reached its retirement years.

At the other end of the age distribution, an increasing share of the adult population (defined as those of age 16 or more) in school in their late teens and 20s will have a similar impact. Over this period, the share of the population (of age 16 or more) in school or college has been increasing.

The other key factor to take into account is male and female differences in labor force participation. A half century ago, most women did not participate in the formal labor force, and hence were not counted in the labor force participation rate. Now they do. This has had a major impact on the overall (male plus female) labor force participation rate, and this change over time has to be taken into account.

The impact of these factors can be seen in the key chart shown at the top of this blog. Male and female rates are shown separately, and to take into account the increasing share of the population in their retirement years or in school, the figures presented are for those in the prime working age span of 25 to 54. The trends now come out clearly.

The most important trend is the sharp rise in female participation in the formal labor force, from just 34% (of those aged 25 to 54) at the start of 1948 to a peak of over 77% in early 2000. The male rate for this age group, in contrast, has followed a fairly steady but slow downward trend from 97 to 98% in the early 1950s to about 88% in recent years. As a result, the combination of the male and female rates rose (for this age group) from 65% in 1948 to a peak of 84% in 2000, and then declined slowly to 81% now.

Seen in this way, the recent movement in the labor force participation rate does not appear to be unusual at all. Rather, it is simply the continuation of the trends observed over the last 68 years. The male rate fell slowly but steadily, and the female rate at first rose until 2000, and then followed a path similar to the male rate. The overall rate reflected the average between these two, and was driven mostly by the rise in the female rate before 2000, and then the similar declines in the male and female rates since then.

F. The Female Labor Force Participation Rate as a Ratio to the Male Rate

Finally, it is of interest to look at the ratio of the female labor force participation rate to the male rate:

This ratio rose steadily until 2000. But what is perhaps surprising is how steady this ratio has been since then, at around 83 to 84%. An increasing share of females entered the labor force until 2000, but since then the female behavior has matched almost exactly the male behavior. For both, the share of those in the age span of 25 to 54 in the labor force declined since 2000, but only slowly and at the same pace. The male rate continued along the same trend path it had followed since the early 1950s; the female rate first caught up to a share of the male rate, and then followed a similar and parallel downward path.

Why the female and male rates moved at such a similar and parallel pace since 2000, and at a 83 to 84% proportion, would be interesting issues to examine, but is beyond the scope of this blog post. One hypothesis is that the parallel downward movements since 2000 reflect increasing enrollment in graduate level education of men and women older than age 25 (and hence included in the 25 to 54 age span). But I do not know whether good data exists for this. Another hypothesis might be that very early retirement (at age 54 or before), while perhaps small, has become more common. And the ratio of the female rate to the male rate of a steady 83 to 84% might reflect dropping out of the labor force temporarily for child rearing, which most affects women.

More data would be required to test any of these hypotheses. But it appears to be clear that long-term factors are at play, whether demographic, social, or cultural. And the pattern seen since 2000 has been quite steady for 16 years now. There is no indication that one should expect it to change soon.

G. Conclusion

The downward movement in the employment to population ratio in 2008 and 2009 reflected the sharp rise in unemployment sparked by the economic and financial collapse of the last year of the Bush administration. Unemployment then peaked in late 2009, as the economy began to stabilize soon after Obama took office, with Congress passing Obama’s stimulus program and the aggressive actions of the Fed. From late 2009, the employment to population ratio was at first flat and then rose slowly, as falling unemployment was offset by a steadily falling labor force participation rate.

But the fall since 2007 in the labor force participation rate did not represent something new. Rather, it reflected a continuation of prior trends. Once one takes into account the increasing share of the population either in retirement or in school (by focussing on the behavior of those in the prime working ages of 25 to 54), and most importantly by taking into account female and male differences, the trends are quite steady and clear. The movement since 2007 in the recent downturn has not been something special, inconsistent with what was observed before.

The implications for the economic programs of the Republican presidential candidates as well as Bernie Sanders on the Democratic side, are clear. While there will be month to month fluctuation in the data, and perhaps some further increase in the labor force participation rate, one should not assume that there is a large reservoir of hidden unemployed who could be brought into gainful employment and allow there to be a large jump in GDP.

Economic performance can certainly be improved. The rate of growth of GDP should be higher. But do not expect a quantum leap. One should not expect miracles.

You must be logged in to post a comment.