There is perhaps no more firmly held view in Republican (and especially Tea Party) circles than that federal government expenditures have exploded under Obama. But it is simply not true. Previous analysis in this blog has shown that total government expenditures (including state and local) traced over the course of each business cycle in the US since the mid-1970s, rose less during the Obama period than in any of the others. Indeed, that analysis indicated that if government spending under Obama had been allowed to increase as much as it did under Reagan following the 1981 downturn, then we would now likely be at or close to full employment.

But when President Obama noted in a speech in Iowa on May 24 that the pace of federal spending had grown at the slowest pace in his term of any presidency in sixty years, the remarks were met with widespread incredulity in the press and on the internet. Given the repeated Republican attacks asserting the opposite, many did not believe it could be true.

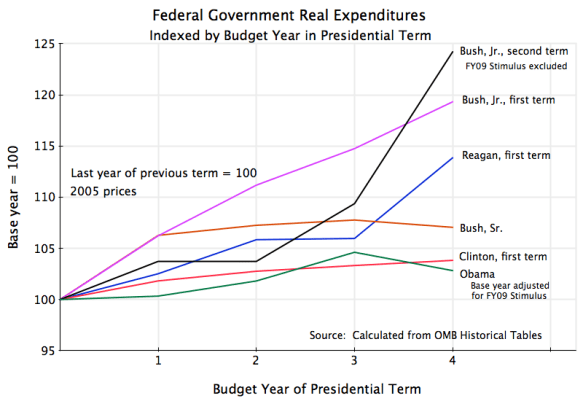

But it is true. The graph above shows the levels of real federal spending in the first terms (and Bush’s second term) of each president since Reagan. Growth in real federal spending in each presidential term prior to that was also higher than under Obama, going back to Eisenhower. (Under Eisenhower there was a fall in real spending, as Korean War expenditures, at a peak when he took office, came down as the war ended. There was an even larger fall during the Truman term as World War II came to an end. But these cases are not terribly relevant.)

The figure above shows real federal spending levels in each presidential term since Reagan, indexed with the year preceding their first budget set equal to 100, and then showing the levels in real (inflation-adjusted) terms for the four budget years of their presidencies. Only the first terms are shown for two term presidents other than Bush Jr., to make it comparable to the Obama term thus far, to reduce clutter in the figure, and because it made no real difference (increases during the second Reagan and Clinton terms were in the middle of the ranges shown above, with four-year increases of 7% and 8% respectively).

Federal government spending under Obama has been largely flat, increasing by less than a total of only 3% in real terms by his fourth budget year (FY13, where I used the budget proposal made to Congress in February by Obama for this figure; any actions by Congress will likely result in further cuts, not increases, in this). The only recent president with spending at all close to this was Clinton in his first term, when spending rose by a total of 4% in real terms. The biggest spending increases by far were by Bush, Jr., in both his first and second terms. Real spending rose by 19% in Bush’s first term, and by 24% in his second term (even adjusting for spending approved as part of the FY09 Stimulus package: see the technical note below). Reagan, revered for his small government conservatism, oversaw an increase of 14% in real government spending during his first term.

The Democratic presidents Obama and Clinton have therefore kept federal government spending tightly under control, while the Republican presidents of Reagan and especially Bush, Jr., oversaw large expansions in real federal spending. Obama’s conservatism on this has certainly hurt the economy at a time when unemployment remains high due to a lack of demand in the aggregate for what such labor could produce. But he has been criticized, without any basis in fact, for the opposite.

———————————————–

Technical Note

It is important to be aware that budget (or fiscal) years do not coincide with presidential terms. Presidents are inaugurated in January, while budget years start in October. A president therefore takes office with a budget year already one-third over, Congressional appropriations already set (or at least largely set), and little ability, with rare exceptions, to influence spending in the year they take office.

Thus in the figure above, the base year of expenditures (set equal to 100) will be the budget year in the middle of which a president took office, and the final year will be the budget year underway at the end of his term. The figures are calculated from data in the Historical Tables issued by the Office of Management and Budget.

The one exception where a president has had a major impact on spending levels in his first year would be spending under the Stimulus package that Obama signed into law, which was approved on February 17, 2009. This package provided for a total of $971 billion in measures, but $420 billion of this was for tax cuts, and $551 billion for spending. Of this $551 billion in spending, only $114 billion (according to the most recent estimates of the Congressional Budget Office) was spent in FY2009, approximately as planned. The figure above adjusts for this, with the $114 billion (equal to $103 billion in 2005 prices) taken out of the fourth year of the Bush second term expenditures, and with the same amount also used to adjust the base year of the Obama expenditures. Without these adjustments, federal government expenditures in the Bush second term would have gone up by a total of 28% (rather than 24%), and Obama’s expenditures by his fourth year would have declined by 0.5% (rather than increasing by 3%).

You must be logged in to post a comment.