I. Introduction

The recovery in employment has been exceedingly weak in the on-going, but slow, recovery from the 2008 collapse. The recovery of GDP has been weak as aggregate demand has simply not been there to absorb increased production. Household consumption has been weak following the collapse of the housing bubble, and monetary policy has been pushed to the limit with Fed interest rates now almost zero but the economy still in a liquidity trap.

The one instrument that could have been used to create demand for output and hence employment would have been increased fiscal expenditures. But as noted in a March 3 posting on this blog, total government spending (including that from state and local governments) has been flat or falling since Obama was inaugurated. Indeed, that blog found that if fiscal expenditure had been allowed to grow as fast as it had in the Reagan years following the downturn that began in July 1981, GDP at the end of 2011 would have been close to full employment output.

The oft repeated Republican alternative view, however, is that the slow recovery in GDP and jobs has been due to overbearing new regulations, and not due to fiscal drag or some other demand side issue. Indeed, Republicans have argued strongly that government expenditures should be cut even further. They have asserted that the recovery in jobs has been weak due to expensive and excessive new regulations instituted by the Obama administration, which have deterred businesses from creating jobs. While more than a bit confused, as we will see below, the argument is that these new regulations have hurt productivity, so businessmen could not profitably employ new workers and hence did not hire new workers.

A convenient summary of this view appeared today in the Washington Post, in the “Right Turn” column of the conservative columnist/blogger Jennifer Rubin (link here to the on-line version). She wrote: “Get Obama out of the way — and with him Obamacare, the Dodd-Frank legislation, a chunk of discretionary spending and the planned tax hikes — and instead put in place his agenda — tax cuts, entitlement reform, reduced regulation, and domestic energy development — and the economy will take off.” The argument falls apart if these measures, and the rest of what has been done during Obama’s period in office, did not result in a collapse in productivity.

This blog will look at whether there is any factual support for this Republican alternative view on the cause of the slow recovery in employment. Did productivity go down after Obama took office? What path has productivity taken over the course of this downturn, and how does this compare to the paths taken in previous downturns? And in reviewing this, we will examine the confusion in this argument on the links between productivity and job growth.

II. GDP and Employment Growth in the Downturns

To start, it is helpful to see what the paths of GDP and employment have been in this downturn, and in comparison to previous downturns. The path of real GDP was shown in the March 3 blog cited above, and is repeated here for convenience:

As was noted before, the path of GDP recovery has been especially slow following the 2008 financial collapse. GDP fell sharply in the first five quarters of the downturn, in the last year of the Bush presidency and into the quarter that Obama was inaugurated (the first quarter of 2009). GDP stabilized soon after Obama took office and then started to grow, but has since grown only slowly. The recovery has been the weakest of any among the six recessions in the US of the last four decades. The earlier blog noted that this can be explained by weak demand for output, due to government spending that has been flat or falling since Obama took office, and exacerbated by the collapse of the housing market.

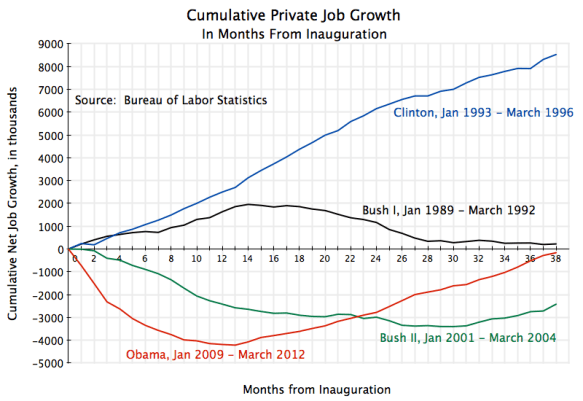

With the weak growth of GDP, it should not be surprising that employment growth in this weak recovery has been exceptionally weak as well:

Employment fell sharply in the year before Obama took office, more than in any of the other downturns of the last forty years. And then, despite the stabilization of GDP, employment continued to fall through 2009 before stabilizing. But the recovery in employment since then has been poor. This employment path has been by far the weakest of any of the six downturns of the last forty years.

III. Labor Productivity in the Downturns

Can this weak recovery in employment in the current downturn be explained by poor productivity growth (a result of excessive regulation), as the Republican argument asserts? Has the path of labor productivity also been an outlier in the current downturn?

Actually, the path of labor productivity has been well within the paths seen in the other downturns:

Labor productivity did in fact fall at first, during the last year of the Bush presidency, although this was not uncommon among the downturns. The fall while Bush was still president was relatively high, but similar to the downturns seen after November 1973 (Nixon/Ford) and July 1981 (Reagan).

But it is interesting to note that labor productivity began to rise quite rapidly immediately after Obama took office. I would not argue that this was entirely due to Obama, especially in the first few months of his term. I am merely pointing out that there is no basis for the assertion that Obama instigated regulations hurt productivity and hence job growth (under the Republican argument) after he took office.

This becomes even more clear if one re-bases the series so that labor productivity in the fifth quarter after the start of a downturn is set equal to 100:

Starting from when Obama took office (in the fifth quarter after the start of the downturn), labor productivity growth has been high, and indeed grew at about the same rate as that seen following the 1981 downturn (during the Reagan presidency). Productivity growth during these two recoveries were not only similar but also the most rapid by a significant margin among the six downturns tracked. The main difference between the two is that productivity growth has slowed in the current cycle over roughly the last year (i.e. starting in quarter 13), while it continued to grow at that point in the recovery from the downturn that began in July 1981. But the difference is not large, and one should not draw strong conclusions from it.

It is a firmly held position in Republican dogma that the “reforms” instituted by Reagan of deregulation, cuts in taxes, undermining of labor unions, and other such measures, led to a miracle of productivity growth from which the economy still benefits. I noted in an earlier posting (see here) that productivity and output growth in the US was in fact slower in the 30 years following Reagan than in the 30 years before. Over a long term perspective, Reagan was not such a miracle. And from the diagram above, we see that over the short term, starting from the same point in the business cycle (five quarters after the peak), the record in terms of productivity growth for the vilified Obama is basically the same as for the sanctified Reagan.

It is not a coincidence that the employment picture finally started to improve in 2011, precisely when productivity growth, which had been strong, started to level off. And this points to the basic confusion in the Republican argument, which some of you may have already seen. By basic arithmetic, the number of employees one needs to produce a given amount of output depends on productivity, but depends on it negatively. That is, if productivity has increased, one needs fewer workers to produce a given amount of output. If one can only sell so much of output due to slack demand, and if productivity growth is strong, then employment growth will be weak. This has been the story of the recovery during the Obama term, and it is only in the last year, when the pace of productivity improvement slowed, that one has seen a more steady increase in the number of employed.

Productivity growth is due to many factors, and for the economy as a whole it will not change quickly due to any policy action. It will vary over the course of the business cycle, as seen in the diagrams above, where it will normally (although not necessarily always) fall at the onset of the downturn (as firms will usually be slow to lay off workers as demand for output slows), and then rise significantly once the recovery begins (as firms will usually also be slow to hire additional workers as demand for output increases, but instead use existing workers more).

The current downturn and recovery was not that much different, although the swings were more extreme this time as the downturn was more extreme. But what was different in the current cycle is that in the recovery (as discussed in the March 3 blog posting), demand from government spending did not increase as it had in previous recoveries, but rather was flat and then fell. Furthermore, demand from housing construction was extremely depressed, due to the size of the housing bubble and subsequent collapse. Recovery in GDP, and hence in employment, has therefore been slow.

IV. Conclusion

There is no factual support for the Republican assertion that overbearing new regulations from the Obama administration has led to weak job growth, due to the negative impact of such regulations on productivity. Indeed, the argument is quite confused, since for any given level of output, higher (not lower) productivity means fewer workers are needed to produce that output, which hurts immediate job growth.

The path of labor productivity in the current downturn and recovery has in fact been within the bounds seen in other downturns and recoveries in the US over the past four decades. If anything, productivity fell somewhat more sharply than in most of the others during the last year of the Bush presidency, and more rapidly than most of the others after Obama took office. And it is this relatively rapid growth of labor productivity during the Obama term, coupled with weak GDP growth (due to fiscal drag and the collapse in housing) which explains the weak recovery in employment.

It should be emphasized that productivity growth is good over the longer term, as it leads to a higher level of output and hence overall income at the full employment level of GDP. But when the economy is operating at less than full employment GDP, higher productivity will translate into fewer jobs than otherwise. The way to resolve this is to bring the demand for output back up to the level of output that could be produced if all resources (in particular labor) were fully utilized. It is a terrible waste, as well as a human tragedy, to allow such unemployment when the needs are so great.

You must be logged in to post a comment.