A. Introduction

A pair of recent news releases on the job market underscore what has been a strong record on job growth during Obama’s tenure as president. On July 8, the Bureau of Labor Statistics released its monthly employment report, while on July 14, the Department of Labor issued its regular weekly report on initial claims for unemployment insurance. The reports show continued strong growth in employment, an unemployment rate that remains below 5%, and initial claims for unemployment insurance that are at a record low as a ratio to total employment.

This blog post will review these developments, with comparisons to the outcomes seen under recent Republican presidents. Obama’s policies have been criticized as harmful to labor by “killing” jobs through over-regulation or by the extension of health insurance under the Affordable Care Act (Obamacare), but this is simply not true. Employment growth has been strong, and the unemployment rate is now at a level which is at, or close to, full employment levels. It might be able to go a bit lower, but not by much.

And because unemployment cannot go much lower, job growth going forward will necessarily slow down. When one is at full employment, job growth cannot be greater than growth in the labor force, and growth in the labor force is primarily determined by demographic factors. While there can be month to month fluctuations, as the number choosing to enter or remain in the labor force can fluctuate (and there will be statistical variation as well, as these figures are all based on surveys), these fluctuations will even out over time as they are fluctuations around a relatively steady long-term trend (see this earlier blog post for a discussion).

This blog post will review these figures on employment growth during Obama’s tenure, and what might now be expected going forward.

B. Job Growth, the Unemployment Rate, and Initial Claims for Unemployment Insurance

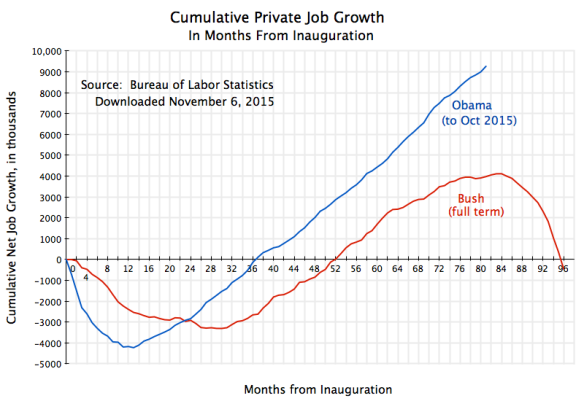

The charts at the top of this post show growth in the number of jobs, separately for private jobs and for government jobs, cumulatively from the month of inauguration for Obama and similarly for George W. Bush.

Private job growth has been strong and remarkably steady under Obama since the trough reached at start of 2010, one year after he took office. During his first year in office, Obama’s stimulus program plus aggressive Fed actions succeeded in turning around an economy that was in full collapse as he took office. There have been 14.8 million new private jobs gained since that turnaround. The contrast with Bush is stark. Private job growth under Bush was not only less in absolute amount, but also collapsed in his final year in office as the economy went into free fall following the bursting of the housing bubble.

Also in contrast to Bush (and every other recent president), government jobs have fallen during Obama’s tenure, with 460,000 less now than when he took office. Total jobs have not grown because of additions to the public sector payroll: There are fewer government jobs now than when Obama was inaugurated.

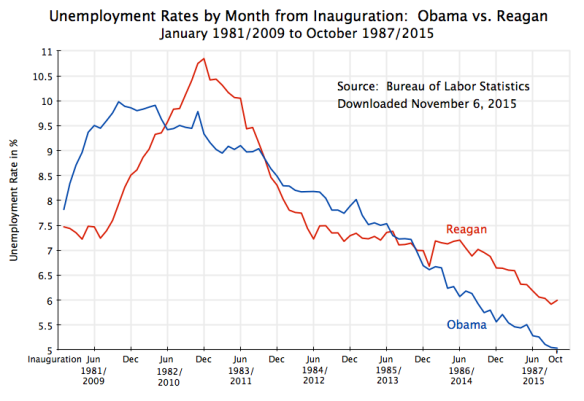

With the overall job growth, unemployment has fallen steadily, from a peak of 10.0% in October 2009 to just 4.9% now:

Furthermore the unemployment rate has been at 5.0% or below since October 2015. With full employment traditionally viewed as an unemployment rate of around 5% (there is always some friction in the market), the unemployment rate cannot go much below where it is now. And the unemployment rate is well below what it was when Reagan was in office, at the same point in their respective administrations.

Furthermore the unemployment rate has been at 5.0% or below since October 2015. With full employment traditionally viewed as an unemployment rate of around 5% (there is always some friction in the market), the unemployment rate cannot go much below where it is now. And the unemployment rate is well below what it was when Reagan was in office, at the same point in their respective administrations.

Finally, the weekly report on initial claims for unemployment insurance (issued by a different unit within the Department of Labor) shows claims are now at a record low level when measured as a ratio to number employed:

Initial claims for unemployment insurance as a ratio to employment has never been so low since at least 1967, when the data series first began to be collected. Indeed, it has been at a record low since late 2014. Workers are not being laid off.

This employment record is therefore strong. Had Mitt Romney been elected president in 2012, one can imagine what he and his party would now be saying of such a record. In May 2012 during the campaign, Romney said that his policies would get unemployment down to 6% by the end of his first term (i.e. by January 2017). And this was viewed as a stretch. But it was achieved under Obama by September 2014, less than half way through his term. And unemployment under Obama has now been at 5.0% or less since October 2015.

C. What to Expect Going Forward

While job growth has been strong under Obama, one must also be aware that this cannot go on forever. A slowdown has to occur. While jobs can be (and should be) added quickly when unemployment is high, so that the unemployed can gain jobs, once one is at or close to full employment, this has to slow down. When this happens, it should not be a surprise.

When an economy is at full employment, the growth in the number of those employed can only rise with growth in the labor force. And this depends primarily on demographic factors. While there can be short term fluctuations (including fluctuations in the figures arising from the statistical estimates, as they are based on surveys of households), these will even out over time.

Since the trough reached in February 2010, total employment has increased by 14.4 million, while private employment has increased by 14.8 million (government jobs have been reduced). The average increase per month over this period was 190,000 for total employment and close to 195,000 per month for private employment. These are also not far different for the monthly averages of just the past 12 months, of 204,000 for total employment and 194,000 for private employment.

But this cannot continue. The labor force is growing at a pace of only 0.5% per year, based on the growth over the decade of June 2006 (when unemployment was 4.6%) to June 2016 (when unemployment was 4.9%). Applied to the current labor force of 158.9 million, growth of 0.5% per year comes to 66,200 additional workers per month. The pace of job growth will have to fall at some point in the not too distant future to about one-third the pace it has averaged over the last year.

A couple of caveats should be noted. First, the rate of unemployment compatible with full employment is not known with certainty, and may well have varied over time. The unemployment rate might fall below 5%, and was indeed in the range of 3.8 to 4.1% during the last year of the Clinton administration. Should it be possible to bring the “full employment” rate of unemployment down by a further 1% point over the course of, say, one year (i.e. from the current 4.9% to 3.9%), then monthly job growth over that year could average 200,000 per month. An additional 1% of the current labor force of 159 million would obtain jobs (1% of 159 million equals 1.6 million, or 133,333 per month over 12 months, plus the trend growth of the labor force of 0.5% per year adds 66,200). But there is still a limit, and while it might not be reached immediately, it is not far off.

Separately, the number in the population that choose to participate in the labor force has varied over time, and could conceivably go higher. Some analysts have indeed argued that it is exceptionally low right now, and can be expected to go higher as the economy returns to full employment and “discouraged workers” start again to seek jobs. But again, there are limits to this, and as I argued in an earlier blog post, I do not see that one should expect a sharp increase. Indeed, the long term trend has followed a steady and predictable path in recent decades (when one separates out the male and female rates), and the male and female rates have both been going downward since the late 1990s. On top of this, the aging of the baby boomers into their normal retirement age means one should expect even slower growth in the labor force over the next ten years than over the last ten years.

Finally, this slowdown in the pace of job growth is what one should expect under ideal conditions, of an economy that is at, and then remains at, full employment levels. Under such conditions, the pace of job growth could average only around 66,000 per month. But the economic expansion under Obama has now been underway for seven full years. Only three other business cycle expansions have lasted so long in US history. Eventually, every expansion has come to an end, and when it does, jobs will decline. The expansion under Obama has continued, but who knows what will happen once a new president takes office next January.

D. Conclusion

The jobs record under Obama has been exceptionally strong. There is no basis for the assertions made by political opponents that his regulatory and other policies have harmed job growth. Faced with an economy in free fall when he took office, Obama was able to engineer a stabilization and then recovery that has brought employment back to full employment levels.

This is not to deny that there are important economic issues. Most importantly, wages have been flat and income distribution has continued to worsen. Furthermore, with the economy now at or close to full employment, the pace of job growth up to now will have to slow in the not too distant future. When it does, one should not be surprised.

You must be logged in to post a comment.