The Senate is now debating, and will likely soon pass, its version of the officially named “One Big Beautiful Bill Act”. While minor changes are possible, its overall impact on the federal deficit and hence on federal debt is unlikely to differ much from the June 27 version that the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) examined. The CBO estimated that this bill would increase the federal deficit by a sum of $3.25 trillion over the ten-year period of FY2025 to FY2034 relative to the CBO’s prior (January 2025) baseline forecast.

This is huge. It will also be highly regressive, based on a CBO analysis of the similar bill passed in the House in May. Despite the overall cost (and consequent federal borrowing to pay for it), the poorest households – and indeed households in the lowest three deciles of the population (the bottom 30%) – will see an absolute fall in their incomes. This is historic. Previous tax cut bills (the primary focus of this bill) saw at least some increase in the after-tax and transfer incomes of the poor. Just not very much, and far smaller than the tax cuts received by the rich. But the “One Big Beautiful Bill Act” (and that is, indeed, the official name) will result in the real incomes of the poor being cut in absolute terms, primarily because the Republicans in both the House and the Senate have reduced the overall impact on the federal deficit by slashing Medicaid.

The impact of the bill on federal debt will also be substantially higher than the figures commonly cited in the press. Those figures come directly from the CBO estimates. For some reason (possibly a legislated rule the CBO must follow), the ten-year cost estimates made by the CBO of bills such as this are the simple sum of the year-by-year estimates of the impact on the deficit in each year. But the ten-year cost will be higher than that simple sum. With the annual deficits higher, the federal debt will be higher, and interest will need to be paid on that higher federal debt starting in year one. More funds will need to be borrowed to cover those interest payments. And there will be interest due on those borrowed funds as well.

Thus the increase in the federal debt over the ten-year period (over and above whatever was in the baseline comparator) will not simply be the sum of the higher deficits in each of those ten years. There will be higher interest costs as well. I have estimated that the resulting higher interest expense exceeds $0.7 trillion, based on the assumption that the increased borrowing will cost, on average, the CBO forecast of the 10-year US Treasury bond rate.

Including interest, the resulting impact on the federal debt after ten years will not be the $3.25 trillion figure from the CBO often cited in press articles on the Senate bill, but rather substantially higher at just short of $4 trillion:

|

in billion $ |

FY2025 to 2029 |

FY2025 to 2034 |

| CBO Estimated Outlays | -$274.2 | -$1,212.7 |

| CBO Estimated Revenues | -$2,271.0 | -$4,466.0 |

| Net Effect on the Annual Deficit | $1,996.8 | $3,253.3 |

| Increase in interest due | $160.9 | $736.9 |

| Net Effect including Interest | $2,157.7 | $3,990.2 |

| Change in Debt in 2029 & 2034 | $2,157.7 | $3,990.2 |

Focusing on the ten-year (FY2025-34) costs, the CBO estimates that under the Senate bill being considered (as of June 27), overall outlays in the budget would be reduced by $1.2 trillion. Most of this would come from cuts to Medicaid ($725 billion), with overall health programs cut by $1.15 trillion. There would also be major cuts to food stamps (SNAP) and similar food programs ($186 billion).

But spending would be higher on certain favored programs, such as for the military ($173 billion including the Coast Guard) and programs to block immigration ($169 billion). The CBO estimates there would be a net reduction in fiscal outlays of $1.2 trillion.

But the core of the bill is tax cuts, primarily for the benefit of those with high incomes. Most of the cost will come from extending the tax cuts enacted in late 2017 during the first Trump administration. In the 2017 bill, those tax cuts were set to end in 2025. Formally ending the measures in 2025 made it appear that the full cost of the 2017 tax cut measures would (over the standard ten-year time horizon Congress uses) be less than under the real intent of making them permanent. That cost has now become apparent.

The total cost of the revenue measures in the Senate bill – as included in the CBO estimates (where the CBO figures in fact come from estimates made by the Joint Committee on Taxation of Congress) – are close to $4.5 trillion over the ten-year period. Netting out the $1.2 trillion of reduced expenditures, the ten-year cost – as often cited in the press – is $3.25 trillion.

But interest will be due on the debt that will be incurred to fund the higher deficits. When that interest is included, the federal public debt will not be a $3.25 trillion higher after ten years, but $4 trillion higher.

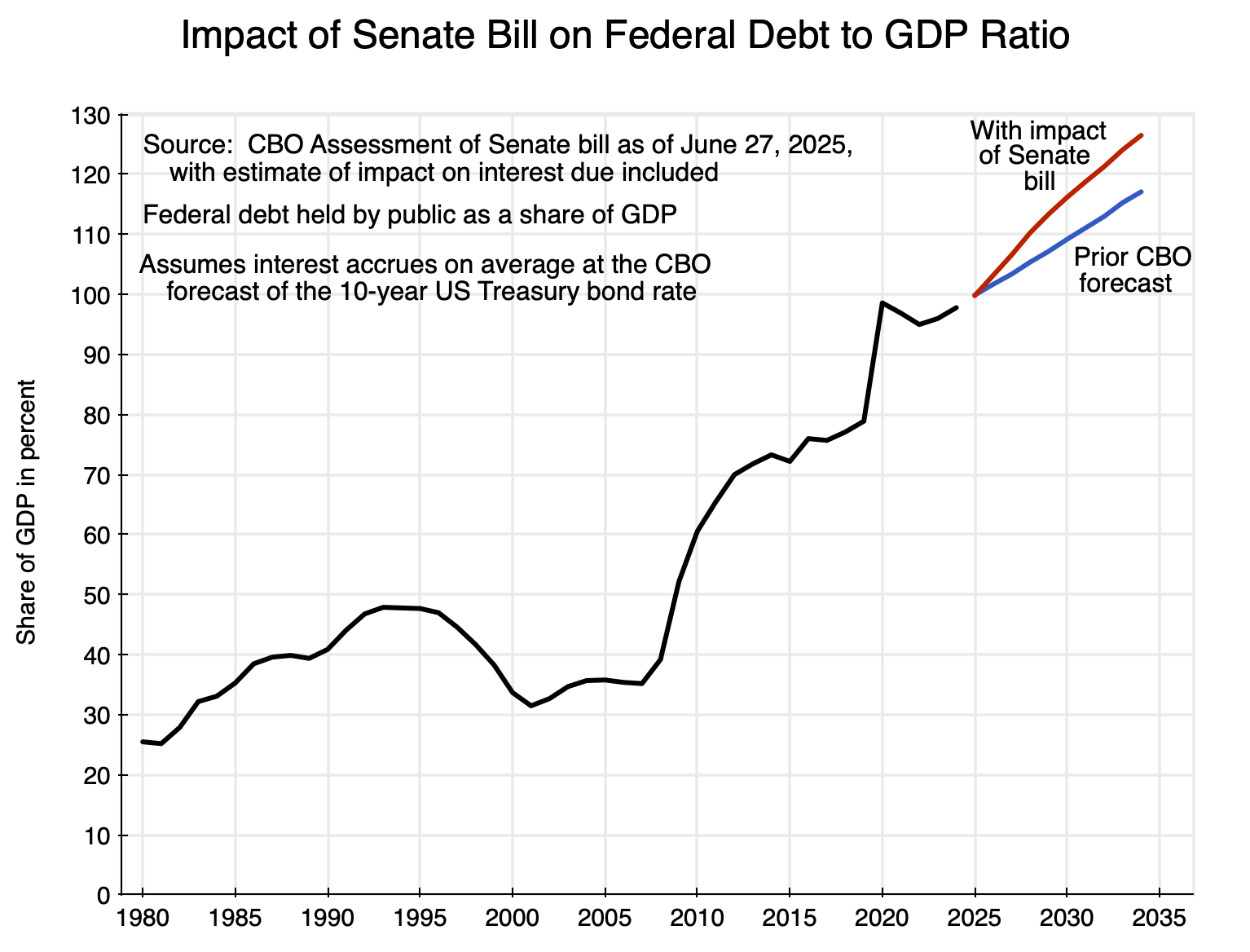

The resulting path for the federal debt to GDP ratio is shown in the chart at the top of this post, with the debt to GDP ratio shown going back to 1980 to provide context. For the 2025 to 2034 period, the curve in blue shows what it would be under the prior (January 2025) CBO forecast (which assumed current law would be followed), while the curve in red shows what it would be if the Senate bill is passed and then approved also in the House and signed into law by Trump.

The federal debt to GDP ratio (defined as the net federal debt held by the public, where internal trust fund and other accounts – such as for Social Security – are netted out) is now close to 100% of GDP. It was already on a rising path in the prior (baseline) CBO forecast released in January (a forecast based on budget and tax law as it stood at the time). With the Senate bill it will now rise even faster. Fiscal deficits will soon exceed 7% of GDP under Trump – unprecedented in times of full employment other than during World War II – and the federal debt to GDP ratio will soon exceed the record set in 1946 when it hit 106% of GDP. Under the Senate bill, it is expected to exceed 106% of GDP by 2027, and will reach 126% of GDP by 2034, with no sign of it falling from there.

One should also note that the CBO forecasts of GDP and the federal deficit are long-term, and of necessity the CBO can only forecast some long-run path of steady growth. In reality, of course, there will be fluctuations around any such path; it is just impossible to know when. But when there is a downturn (and it is a matter only of when, not whether, with that likelihood especially high due to the chaos of the Trump administration), the fiscal deficit will rise and should rise. The federal government has an important responsibility to help stabilize the economy. But that higher fiscal deficit will add to federal debt, and the federal debt to GDP ratio will be higher following any such downturn even when GDP has returned (hopefully) to its previous long-term path.

The CBO forecast of the debt to GDP ratio in the outer years is therefore likely to be an underestimate. By 2034, it could be a good deal higher than 126% of GDP unless Republicans in Congress finally recognize that their cuts in taxes are irresponsible.

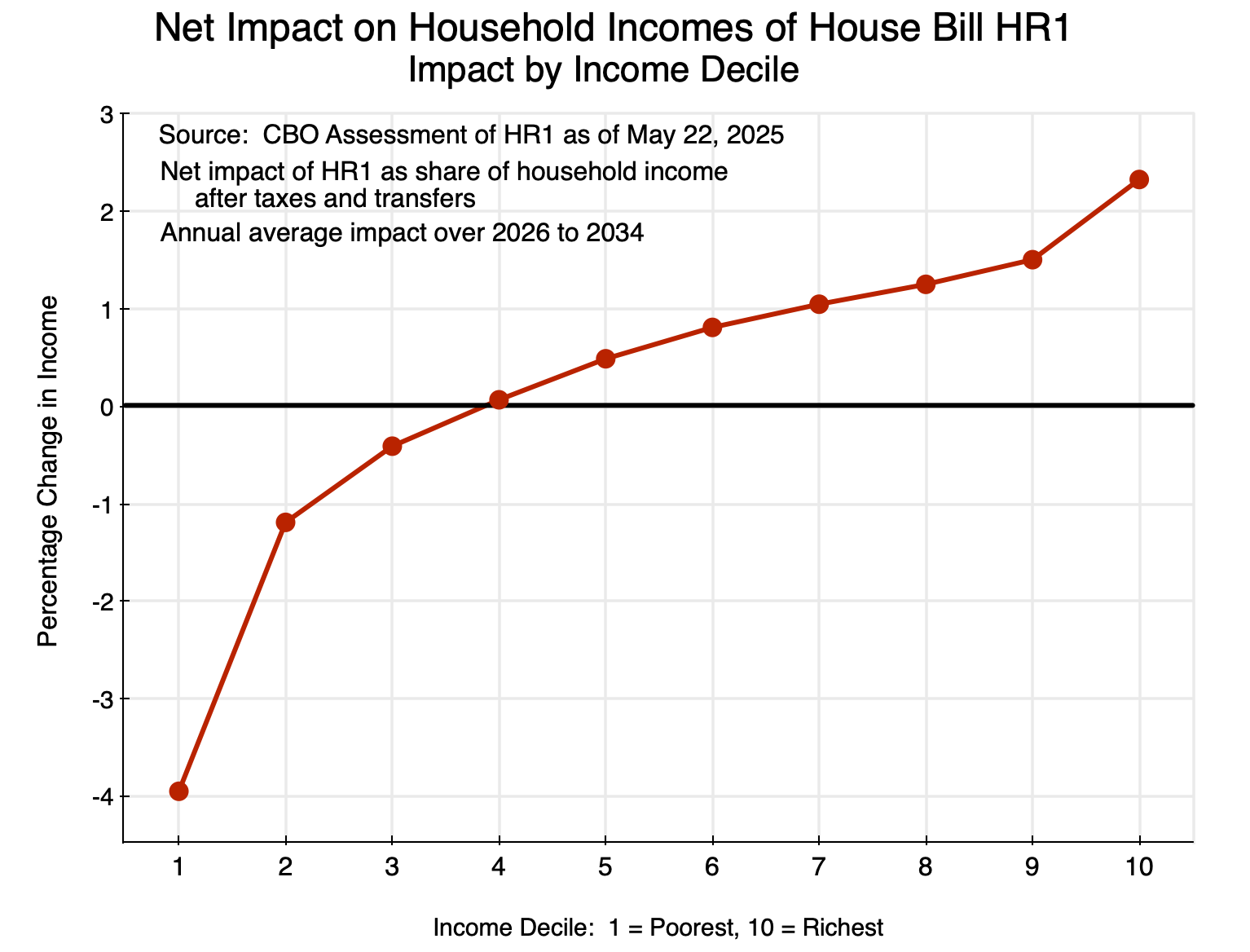

In addition, not only are the measures included in the “One Big Beautiful Bill” tremendously costly, they will only be of benefit to those with higher incomes. Based on the earlier version of the One Big Beautiful Bill (HR1) passed by the House in May, the CBO estimates that the lowest three deciles of households will see their absolute incomes (post taxes and transfers) reduced. The CBO issued its estimates for this bill on June 12. It is not clear whether the CBO will do a similar analysis for the specific Senate bill now being considered, and if so when it would come out. However, the primary measures in the House and Senate versions of the bill are similar, and the distributional impacts will likely be similar.

The CBO estimates of the impacts on households by decile of income of the version of the bill passed by the House (as a percent of household incomes) were:

The poorest decile of households would be especially adversely affected. They would lose 4% of their incomes in absolute terms, with this is in a bill that is being funded primarily by increased federal borrowing. Households in the second and third deciles would also lose in absolute terms, while those in the fourth decile would see (on average) almost no impact. Higher income households then gain progressively more, with especially large gains for the richest (highest decile) households. Note that this is presented as percentages of household incomes, after taxes and transfers. Since incomes are much higher for the highest income households, the absolute dollar gains are especially high for the richest households.

There has never before been such an expensive and highly regressive measure passed by Congress. But it appears this bill will soon be passed and signed into law by Trump.

You must be logged in to post a comment.