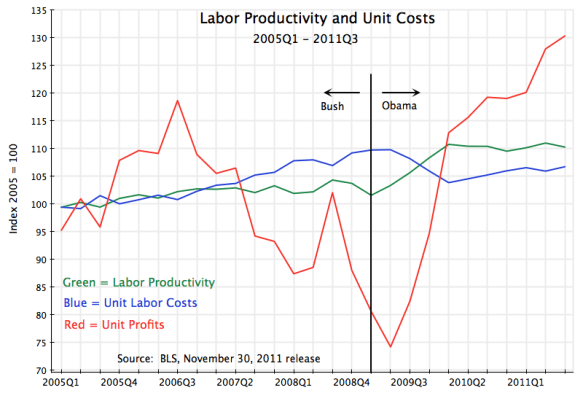

In the post immediately preceding this one (see directly below, or here), I noted that a glance at the economic data makes clear that productivity and profitability have both increased under Obama. Hence, the argument made by Mitt Romney and the other Republican candidates that onerous regulations imposed by Obama are the cause of disappointing job and output growth, is simply not correct. If new regulations were such a problem, one would have expected productivity and especially profitability to have suffered, and yet both have improved. Indeed, profitability has sky-rocketed.

For convenience, here is the basic graph again:

But this naturally then also raises the question of why productivity and especially profitability have gone up by so much under Obama. Indeed, some might wonder whether Obama’s administration has deliberately favored profits at the expense of wages.

While a full analysis cannot be done here, I find no reason to jump to such a conclusion. The path of profits is what one would expect over the last few years, with the sharp collapse in output at the end of the Bush Administration and then only a slow recovery with unemployment staying high. There is the separate issue of the longer term trends, where profits have been growing as a share of National Income since about 1980 (for the last decade, see here, and for the underlying data and the longer term see the BEA data at here). But the fluctuations over the last few years can be well understood in terms of the short term dynamics of the economic collapse and subsequent slow recovery.

Specifically, profits fell sharply in the economic downturn at the end of the Bush Administration, and started to to fall (per unit of production) as far back as 2006. It is worth noting that housing prices peaked in the first half of 2006, and the economy began to slow after that. A collapse in profits when the economy collapsed is as one would expect.

In response to the economic downturn, the Federal Reserve Board cut interest rates, ultimately to historically low levels of essentially zero for rates on risk-free assets. Coupled with other aggressive Fed measures, as well as the TARP program to stabilize the banks (launched by Bush) and then the Obama stimulus program, the collapse was halted and the economy then started to grow in the middle of 2009. Profitability then recovered.

The business response to the downturn was to lay off workers, as they always do in a downturn, and then later they invested in new machinery and equipment. The investment was spurred in part by the low interest rates following from the Fed policies, and indeed the recovery in non-residential private fixed investment was surprisingly strong (see here). Both these actions increased labor productivity, as shown in the diagram above.

But aggregate demand growth remained sluggish, despite the growth in private investment. The downturn was due primarily to the bursting of the housing price bubble that the Bush Administration regulators had allowed to build up (or at least made no attempt to limit). As housing prices collapsed, home owners became poorer and many ended up with mortgages that were larger than the now lower values of their homes. Stock prices also fell, hurting retirement and savings accounts. Coupled also with worries generated by high unemployment, households hunkered down to consume less and try to save more. Private consumption stagnated. And after the Obama stimulus plan was passed (helping to stop the free-fall in output and to turn around the economy), political pressures from the Republican Party and especially the Tea Party wing made it impossible for government to maintain a high enough demand to fill in the still large gap in aggregate national demand.

As a consequence, the recovery in growth was limited and unemployment has stayed high. This has kept wages largely flat. But labor productivity rose due to the large early lay-offs and later the growth in business investment. With wages flat but labor productivity higher, unit labor costs fell.

In addition, there are non-labor costs (not shown in the diagram) which also fell. The main component of such costs that fell was interest payments, which the Fed reduced to the maximum extent it could to try to spur the economy.

With both unit labor costs and non-labor costs down, profits rose and rose sharply.

You must be logged in to post a comment.