In those countries where the spread of Covid-19 was not addressed early, all that policy-makers could then do to break its exponential growth was to lockdown the economy. Schools were closed; non-essential businesses such as theaters, retail establishments, barbershops and hair salons, and similar were also all closed; workers were told to work from home whenever possible; and travel by other than private means was sharply curtailed.

This did succeed in reversing what had been an exponential rise in the spread of the disease, although at a tremendous cost to the economy. While figures are not yet available on the extent of the downturn, it is clear that this will be the sharpest fall in the US economy since at least the Great Depression. And the suddenness of the fall is unprecedented.

But as noted, the lockdowns did stabilize the number each day of new cases and of deaths, and started to bring those numbers down. The disease was still spreading, but not at the pace of before. There is now pressure from some quarters to lift or even fully end those lockdowns, and that process has indeed already started in much of the US as well as in other countries. It is still too early, however, to say whether such easing will lead to a resurgence of the disease. As was seen in January through March, several weeks will go by before one observes whether the number of daily cases will have been affected, and a further two or three weeks before one will see an impact on the daily number of deaths.

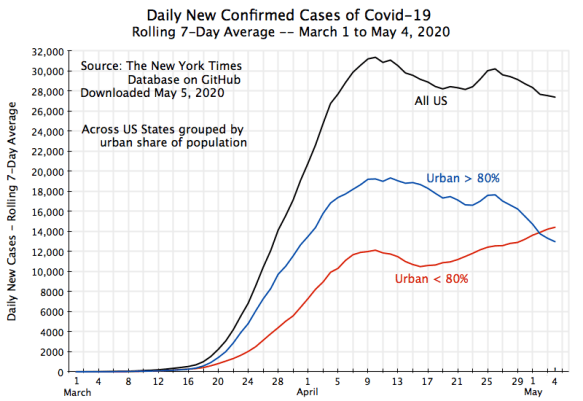

One can, however, at this point examine what the impact was of the lockdowns on the spread of the disease. For the US, those lockdown measures were introduced starting in mid-March and lasted through end-April before they started to be partially lifted in certain jurisdictions. And one can compare the US record to that of a number of Western European nations who also failed to stop the spread of the virus early, who then had to impose lockdown measures to break the exponential growth and start to bring it down.

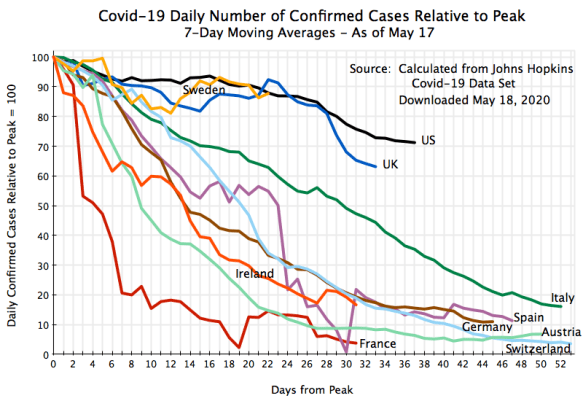

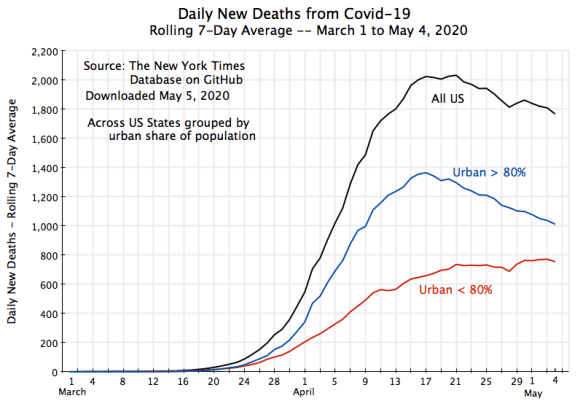

The chart at the top of this post shows how the US record compares to that of a number of Western European countries in terms of the number of daily deaths from Covid-19. It is not good. The US is an outlier, with significantly less of a decline in the daily number of deaths than what all of these comparator countries have been able to achieve.

The chart tracks, by days from the peak day in the country, the daily deaths from the disease (using 7-day moving averages to even out the day to day fluctuations in the statistics), with the figures for each country indexed to 100 for the number of deaths on its peak day. The data cover the period through May 17, and were calculated from the cross-country data assembled by Johns Hopkins.

Thus, for the US there were 29 days (as of May 17) since the peak day in the US of April 18, and by that point the number of daily deaths (using 7-day moving averages) was about 65% of what it was on the peak day. In terms of absolute numbers, the US had 2,202 deaths (in terms of the 7-day average ending on that day) on April 18, and by May 17 (29 days later) the number of deaths had fallen to 1,434 (or 65% of 2,202).

European countries all did better. By 29 days after their respective peaks, the number of deaths had fallen to 47% of what it had been in the UK, and to just 13% of what it had been in Austria (with Ireland tracking even lower, but only on its day 22). The other European countries are all in between. More could have been added. I had originally included five other Western European countries in the chart, but it was then hopelessly cluttered. So I removed those five as they were generally smaller countries (Belgium, the Netherlands, Denmark, Finland, and Portugal), plus their curves all fell in between those of Ireland on the low side and the UK on the high side.

Would the record be different if one drew a similar chart for the number of confirmed cases rather than the number of deaths? Not really:

Here the UK curve tracks more closely to the US curve until day 28 from the respective peaks, but then fell below. While this is speculation, one wonders if those in the UK started to take the social distancing measures more seriously once their prime minister, Boris Johnson, ended up in the intensive care unit of a hospital due to the disease (where one should keep in mind that the number of cases will then be affected only several weeks later).

Sweden may also be of interest. In contrast to other countries, Sweden never issued legally binding lockdown orders, but rather just guidelines. The result, however, was that the number of cases has not come down much from its peak (see the chart). While still early, the number of daily new cases is close to 90% of what it was at its peak. This is similar to what it was for the US at the same point in terms of the number of days from the respective peaks. The UK path was also broadly similar at that point.

There is a difference, however, in terms of how far deaths had come down (the chart at the top of this post). The path for Sweden has been below that of the US and in the range of other European countries. From these observations alone one cannot say why Sweden has seen a greater reduction in its daily number of deaths (relative to their respective peaks) despite a similar number of cases as the US (relative to their peaks). It might be because Sweden enjoys a much better health care system than the US (despite the US spending 60% more than Sweden as a share of GDP). The age composition of those coming down with the disease might also be a factor, if younger people are, on average, a higher share of those being infected in Sweden than in the US.

But overall, the key question is why has the US performed more poorly than all the others in bringing down the number of deaths? There are a number of possible reasons, and these reasons are not mutually exclusive – they could all be contributory. They include:

a) There was no national lockdown order given, but rather different states issued their orders at different times, mostly between mid-March and the beginning of April. Indeed, a few, generally less populous, states never even issued formal lockdown orders, but simply guidelines. This would spread out the impact, leading to less of a fall in the number of deaths relative to the national peak for any given day.

b) Those lockdown orders varied greatly in terms of their degree of strictness. Some were strong, and some notably lax. Furthermore, enforcement was typically lax. The lockdown orders were usually more serious (and much more seriously enforced) in Europe (but with Sweden as an exception).

c) Cultural factors undoubtedly also entered. Some Americans took social distancing measures seriously – others did not. Indeed, some have been especially loud and insistent on not obeying such orders, in a childish display of contrariness. They assert they have a constitutional right to do as they please (even if this may infect others with a deadly disease).

But perhaps the most important reason for the poor record of the US has been the failure of responsible presidential leadership. There has been no coherent, and scientifically informed, national policy. Trump spent two months denying that the virus was a concern, and the US failed to take the critical early actions which could have stemmed the spread (as the developed countries of East Asia and the Pacific were all able to do, and successfully so). Then, when he was finally forced to admit the obvious (spurred more by a crashing stock market than by the disease itself), he has only reluctantly backed the measures needed to address the crisis. And he has personally not modeled the behavior that the federal government’s own guidelines call for:

a) He refused, and continues to refuse, to wear a mask in public.

b) He continued to shake hands with those close by (leading to awkward, and amusing, moments when the other party had begun some other action of greeting).

c) Rather than follow the social distancing guidelines at his highly publicized daily press briefings, for several weeks he had for the cameras a large number of officials and assistants all standing shoulder to shoulder around him.

d) Most recently, Trump confirmed that he has started to take the controversial drug hydroxychloroquine, despite FDA warnings that to do so was dangerous. Indeed, a recent study found that a higher share of Covid-19 patients who took the drug ended up dying than did those not given the drug. Along with some of his other suggestions (such as to examine ingesting bleach or some other disinfectant to kill the virus – which health officials hastened to tell everyone not to do as it could kill them), Trump has conveyed to the public a disrespect for science and instead to do what he believes “in his gut”.

Coupled with Trump’s twitter outbursts (including the early encouragement of small, but well-organized, groups of gun-brandishing demonstrators in several states calling for an immediate lifting of the lockdown measures), it should not be a surprise that the US has been a laggard compared to what other nations have been able to accomplish.

Politicizing this public health crisis, as Trump has, will now also make it more difficult to emerge from it. Guidelines that had been prepared by the CDC on how to safely reopen the economy, and which would have been issued on May 1, were instead suppressed by the White House. Trump instead announced (following intensive lobbying by affected industries), that he did not want cautions to continue, but rather that everything should be quickly reopened back to “where it was” three months ago.

With such political pressures superseding the recommendation of health professionals, many will approach any opening even more cautiously than they otherwise would have. With uncertainty as to whether restaurants, say, were re-opened because it was truly safe or because of political pressures, many will hold off on patronizing them for an extended time. I certainly will.

You must be logged in to post a comment.