No price index is perfect. Assumptions need to be made on what to include and how to include it. Based on those decisions, the resulting price indices (and hence inflation rates) can differ and differ significantly. And this can affect policy.

No price index is perfect. Assumptions need to be made on what to include and how to include it. Based on those decisions, the resulting price indices (and hence inflation rates) can differ and differ significantly. And this can affect policy.

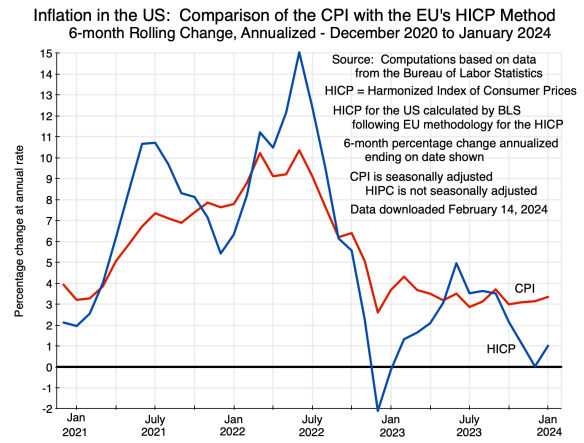

In this context, it is interesting to compare what inflation would be when calculated as the US does for the widely followed consumer price index (CPI), or if it were calculated according to the standard followed in the European Union for what it calls the harmonized index of consumer prices (HICP). Both are reasonable measures, but the resulting inflation can be quite different, as seen in the chart above. With the CPI, the Fed may conclude inflation is still too high – above its 2% target. But calculated as Europe does, one could conclude that inflation is now too low.

This short post will look at the differences and the primary reasons for them. There are lessons to be learned. In particular, it is important to understand what lies behind various statistical measures – including, but not only, any measure of inflation – and not blindly focus on just one when arriving at policy decisions. The Fed in general does, and the Fed’s Board has an excellent staff to advise on developments in the economy. But the media often does not consider such distinctions.

The chart at the top of this post shows the 6-month rolling average percentage changes in prices (at annualized rates) for the period from December 2020 through to January 2024. Both measures are for the US, and both are calculated by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) based on the same data on prices that the BLS collects. The CPI data can be found here, while US inflation based on the HICP methodology as calculated by the BLS can be found here. The BLS notes that its calculations of US inflation based on the HICP methodology are carried out outside of the “official production system” (as it calls it), and are more in the nature of a research project. But the BLS uses the same underlying data for the HICP measure as it uses for its regular CPI calculations.

The HICP methodology was developed as Europe moved to greater monetary integration, culminating in the creation of a common currency – the euro – as well as the European Central Bank (the ECB). The ECB has – similarly to the Fed – the objective of targeting a 2% rate of inflation. For this, it obviously needs to know what inflation is in the Eurozone. But the member nations of Europe that came together to adopt the euro as a common currency (currently 20 nations) had each long had their own way of estimating inflation within their countries, with various methodologies used.

A common approach needed to be adopted, and starting with regulations issued in 1995, the participating nations agreed to what was labeled the “harmonized index (or indices) of consumer prices” (HICP). The statistical agencies of the EU member countries would follow that common methodology, and report their results to Eurostat for aggregation across the countries to a euro-wide index of inflation for use by the ECB. The HICP is now used also for international comparisons of inflation, and it is in this context that the BLS prepares its HICP inflation index for the US.

There are a number of differences between the approaches used for the HICP and for the CPI that lead to the differences in the inflation rates seen in the chart above. The key ones are:

a) The HICP only includes prices of goods and services where there are direct monetary expenditures. The CPI, in contrast, includes estimates of what the implicit costs are of certain services where there are not such direct expenditures. The most important of these are the services provided in owner-occupied homes. The CPI assumes that rents are implicitly being paid at rates similar to what is being paid by those who actually do rent. As was discussed in a post on this blog from last May, the way rents are adjusted (where rental contracts are typically for a year) leads to a lag of up to a year in observed rental rates adjusting to pressures that affect rental rates. As discussed in that post, this long lag has led to a divergence in observed inflation rates in the past year for the shelter component of the CPI in comparison to the CPI for all goods and services other than shelter.

Inflation in the shelter component of the CPI has been the primary cause of inflation remaining above the Fed’s 2% target. Inflation in all goods and services in the CPI other than shelter moderated greatly in mid-2022 and has since fluctuated between zero and 2%. But the shelter component of the CPI has kept the overall CPI at between 3 and 4% since mid-2022. With the HICP leaving out the cost of shelter on owner-occupied homes (it includes it for those who rent), it is not surprising that inflation as measured by the HICP has been well below inflation as measured by the CPI.

b) Also important to understanding the differing figures is that the HICP methodology does not include seasonal adjustments. While seasonal factors can be important, adjusting the figures to reflect that seasonality is technically difficult. The HICP methodology, as adopted by the EU, leaves it out. This probably explains the low rates observed in the chart for HICP inflation seen in each of the six-month figures ending in December, with relatively high rates seen in each of the six-month figures ending in June.

Inflation as measured by the HICP will likely therefore go up in the coming months from the 0.0% rate observed for the six months ending in December 2023 and the 1.0% rate ending in January 2024. Using a rolling 12-month average will mostly resolve such seasonality differences, and a chart of this will be examined below. It shows 12-month rates for the HICP (both for the overall HICP and for a core HICP that leaves out food and energy) fluctuating around a 2% rate starting in June 2023 and continuing at least until now.

c) There are a number of other technical differences, but these are likely less important for the issues being considered here. For example, the HICP adjusts the weights used to calculate the overall HICP index (and its component sub-total indices) only once a year. The CPI, in contrast, is what is called a chain-weighted index where the weights are changed each month to reflect changing expenditure shares. But this is probably not terribly important as the weights do not change even year to year by all that much.

Also, the HICP – if one strictly followed the formal methodology – includes prices faced by the rural population. But the BLS only collects price data from the major urban areas for the CPI, which means that the HICP for the US will only reflect urban prices. That does, however, then mean that there will be less of a difference between the HICP as estimated for the US and the standard CPI for the US. But it also then means comparisons of inflation across countries (where other countries include estimates for prices in rural areas) will not be as reliable.

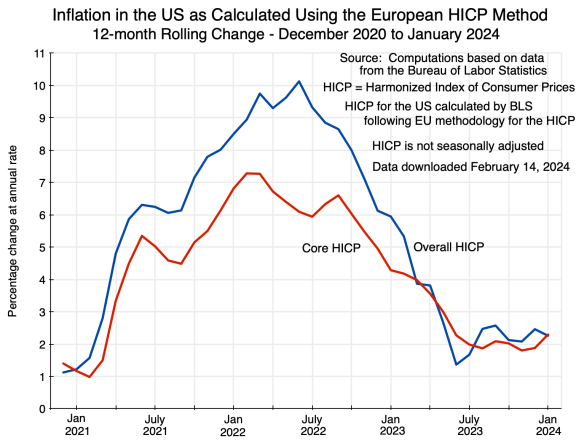

Finally, the year-on-year inflation rates for the HIPC are of interest. They have the advantage of mostly not being affected by seasonality issues (there can still be some seasonal effects, given how the seasonal adjustment algorithms work), but have the disadvantage of not capturing turning points in inflation trends as well.

The year-on-year rates for the US of both the overall HICP and the core HICP have been:

In terms of the year-on-year measures (12-month rolling changes ending on the dates shown), both the overall HICP and the core HICP have fluctuated at rates of between 1 1/2 and 2 1/2% since the 12-month period ending in June 2023. It has remained within that narrow range for 8 months, or two-thirds of a year. If the US measured inflation like Europe does, one would conclude that the Fed should now be allowing interest rates to fall from their current relatively high levels (aimed at reducing inflation) down to more neutral levels.

Inflation in the US as measured by the CPI remains above the Fed’s 2% target primarily due to inflation in the shelter component of the index. But the behavior of the cost of shelter has been special. This is in part due to the lag built into how the cost of shelter services is estimated for the CPI (due to reliance on estimates of rental-equivalent costs, as discussed in the post from last May cited above). But there have also been other factors in recent years due to impacts arising from the response to the Covid crisis and then a rebound that came with the recovery from that crisis. Those issues will be discussed in a subsequent post on this blog.

========================================================

Update – February 17, 2024

From comments I have received on this post, I see that some of the points should be clarified. The basic message was clear enough: That if the US were using the measure of inflation used in Europe, one would conclude that inflation is now at around the Fed taget of 2% and that the Fed should therefore consider allowing interest rates to fall back down to more neutral levels. The primary reason why inflation in the US as measured by the CPI has remained above the Fed’s 2% target has been inflation in the cost of housing services (which is estimated based on the cost of rental equivalents). And the estimates for housing are special, both due to lags in how rental rates are determined and special circumstances arising from the Covid crisis and the recovery from it.

The HICP measure used in Europe treats housing differently, as it measures the prices only of goods and services actually paid for, and not – as for owner-occupied homes – a service that follows from the ownership of the asset. The US CPI treats the services of owner-occupied homes as if a rent were being paid to yourself, as the owner. This leads to the not terribly intuitive situation where inflation in those implicit rents may be high – which is treated as if it were reducing your real income – but at the same time those rents are being paid to yourself – thus increasing your income. That ends up as a wash. But when we look at what has happened to real incomes as a consequence of inflation, we include the former (those implicit rents are reflected in the CPI) but leave out the latter (incomes are not adjusted for the implicit rents being paid to yourself).

In part for this reason, the European HICP measure of inflation leaves out those implicit rents. But one should not say that the HICP is right and the CPI is wrong (or vice versa). Rather, they are different and it is important to understand the difference.

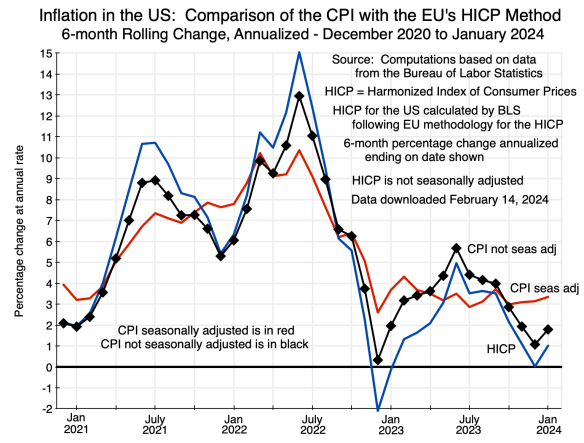

In addition to the treatment of housing services, the HICP measure is not seasonally adjusted. The CPI that is usually the focus of attention is seasonally adjusted. I flagged this on the charts, but it likely would have been useful to have shown as well the not seasonally adjusted CPI series. The charts become more cluttered, but one can then better see what the impact of seasonal adjustment (or the lack of it) has been. And the not seasonally adjusted CPI is more directly comparable to the HICP.

The chart at the top of this post then becomes:

The rolling 6-month annualized change in the CPI is shown here as calculated both from the seasonally adjusted series (in red, and as before) and from the not seasonally adjusted series (in black, and with diamond markers). As noted in the text, the seasonally adjusted CPI (in red) has fluctuated in the relatively narrow range of 3 to 4% (annualized) since the six-month period ending in December 2022 (i.e. since mid-2022). The not seasonally adjusted CPI (in black) has moved on a similar path as the HICP (which is not seasonally adjusted), but always above it – and generally about 1 to 2% points above it (since mid-2022).

Adding the CPI and core CPI series to the 12-month rolling average chart might also have been helpful:

While 12-month changes do not capture the turning points as well as 6-month changes do, the basic story remains the same: Inflation fell sharply in the 12 months leading up to June 2023 (i.e. since mid-2022), but the US CPI measure has been well above what the European HICP measure would indicate inflation has been over this recent period. It is also interesting to note that while the overall CPI has been (since mid-2023) about 1 to 1 1/2% points above the comparable overall HICP measure, the core CPI has been about 2 to 2 1/2% points above the comparable core HICP measure.

While 12-month changes do not capture the turning points as well as 6-month changes do, the basic story remains the same: Inflation fell sharply in the 12 months leading up to June 2023 (i.e. since mid-2022), but the US CPI measure has been well above what the European HICP measure would indicate inflation has been over this recent period. It is also interesting to note that while the overall CPI has been (since mid-2023) about 1 to 1 1/2% points above the comparable overall HICP measure, the core CPI has been about 2 to 2 1/2% points above the comparable core HICP measure.

Why? Again this can be attributed to how the cost of housing services is treated. The HICP measure leaves out the implicit rents paid on owner-occupied housing, but the CPI includes them. In the overall CPI, shelter has a weight of 36% in the overall index, which is significant. Food and energy have a weight of a little over 20% in the overall index. Food and energy are excluded from the core index, so the remaining items have a weight of about 80%. The weight of shelter in the core CPI will therefore be 36% of 80% = 45%. With the cost of housing services rising at a faster pace than the cost of other goods and services, the higher, 45%, weight of housing services in the core CPI leads to the margin over the core HICP (where services from owner-occupied housing are left out and hence have no weight) being greater. Thus the 2 to 2 1/2% margin of the core CPI over the core HICP rather than the 1 to 1 1/2% margin of the overall CPI over the overall HICP.

You must be logged in to post a comment.