A. Introduction

Personal income tax returns in the US were due last week. With taxes on most people’s mind, blog postings on taxes in the US are perhaps timely. This initial post will focus on how much has been paid in taxes in recent years, and whether there is any evidence for the assertion that high taxes have slowed economic growth and job creation. Although it may not feel like it to those have just paid their taxes, the share of taxes in GDP has been at record lows during the Obama administration. Subsequent posts will look at some of the idiocies in the tax code that we as filers face each year, and then at reforms to the tax code, both relatively straightforward (within the current basic structure) and more fundamental.

B. Taxes Have Been at Historic Lows

As noted in a recent posting on this blog, Mitt Romney has repeatedly asserted that high taxes under Obama, due to tax increases under Obama, have led to the disappointing recovery from the 2008 economic collapse. Mitch McConnell, the Republican leader in the Senate, has stated repeatedly in recent years (here is one example) that the US fiscal problem is “because we spend too much, not because we tax too little”. And the new Republican term for the super-rich is that they are the “job creators”, and that therefore taxes on them need to be kept low and cut even further so that they will then “create” new jobs through some kind of trickle-down process.

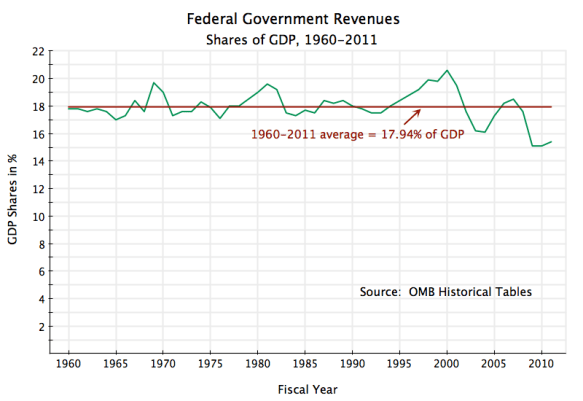

Yet taxes as a share of GDP are the lowest in over a half century in the US (and in fact since 1950). The graph at the top above shows total federal government revenues as a share of GDP, going back a half century to 1960. Taxes (from all sources, not just individual income taxes) averaged almost 18% of GDP over this period, but began a clear downward trend from 2001. The data is from the historical tables made available by the Office of Management and Budget, with data that goes all the way back to the founding of the republic in 1789.

The Bush tax cuts of 2001 and 2003 account for the change in trend. With this change in trend, coupled with the effects of the 2008 economic collapse and then the further tax cuts (not tax increases) signed into law by Obama (discussed below), taxes as a share of GDP reached a low of just 15.1% of GDP in FY2009. And with the tax cuts under Obama, taxes as a share of GDP remained at just 15.1% in FY2010, at 15.4% in FY2011, and are projected to be just 15.8% of GDP in FY2012.

Such a low tax take is unprecedented in the post-World War II United States. Since 1950, taxes were never below 16% of GDP for any individual yearn prior to 2009, despite a number of economic downturns, much less so low for four years straight. It is hard to see how our problems are from taxing “too much” when taxes are the lowest they have been in over 60 years.

Taxes collected in FY09 were low in part due to the 2008 economic collapse. But the economy has been in recovery since the middle of CY2009, albeit weakly. Despite this recovery, and in contrast to the experience in previous cyclical downturns, fiscal revenues have remained at record lows. Average fiscal revenues over the three year period of the year of the economic trough plus the following two years were only 15.2% of GDP in the current downturn. The similar average fiscal revenues over such three year periods in the other five economic downturns of the past four decades were 17.9% of GDP. Cyclical factors cannot explain the current extremely low levels of taxes as a share of GDP. Rather, taxes have been so low due to the downward structural trend that began with the Bush tax cuts, compounded then by further tax cuts signed by Obama.

As was noted in the earlier posting on this blog on Romney’s economic policy address, between February 2009 and February 2012 Obama signed into law almost $1.5 trillion of tax cuts. For convenience, here is the table shown in that post, although with the Payroll Tax cuts now consolidated into one line:

| Tax Cuts Signed Into Law by Obama | ||

| Date Signed | Amount ($b) | |

| A. Tax Provisions in 2009 Stimulus Package | 2/17/09 | $420.0 |

| B. 2010 Tax Cut Package, excl Payroll Tax Cut | 12/17/10 | $769.3 |

| C. 2011 and 2012 Payroll Tax Cuts | 12/17/10, 12/23/11, and 2/22/12 | $227.1 |

| D. Other – Various Dates in 2009 and 2010 | various | $64.2 |

| TOTAL | $1,480.6 |

The $1.5 trillion cost estimate is from figures posted by the bipartisan Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, which in turn came from estimates obtained from either the Congressional Budget Office or the Joint Committee on Taxation of the US Congress. One can also obtain from these sources estimates of how much of the tax cuts would occur by fiscal year, and the estimate, when added up, is that $1.4 of the $1.5 trillion in cuts were in fiscal years 2009 to 2012. These are estimates, made before the fact and subject to uncertainty, but suffice for the basic point here.

Taking these tax cuts as estimated by fiscal year, expressed as a share of GDP, one finds:

| Impact of 2009-2012 Obama Tax Cuts | |||

| Taxes/GDP: Actual | 2009-2012 Tax Cuts Enacted | Taxes/GDP If No Tax Cuts | |

| FY09 | 15.1% | 0.8% | 15.8% |

| FY10 | 15.1% | 2.1% | 17.2% |

| FY11 | 15.4% | 2.9% | 18.3% |

| FY12 proj. | 15.8% | 3.2% | 19.1% |

The tax cuts were large, especially from FY2010 onwards. While taxes as a share of GDP would still have been a relatively low 15.8% of GDP in FY2009 (reflecting the downturn which reached its trough that year), taxes in the subsequent years would have been close to what they have normally been since 1960 (an average of almost 18% of GDP). That is, while taxes as a share of GDP were low in FY2009 largely due to the downturn, they have since remained at historically low levels largely due to the tax cuts signed by Obama.

Critics will of course state immediately that without the tax cuts signed by Obama, GDP recovery would have been even slower. This is true, given the recession. But a reduction of GDP of two or three percent or more, while of course not to be welcomed, would not have had a major impact on these figures on GDP shares of taxes. The denominator would have just been reduced from 100% to 98 or 97%. Furthermore, a reduction in the denominator would (by simple arithmetic) have raised, not lowered, the GDP shares of taxes.

While a more complete modeling exercise would have been desirable, it would still have been a model and subject to all the limitations and criticisms any model will have. The point being made here is just the simple one that the tax cuts signed by Obama were big, and that they were the primary factor leading to the historically record low shares of taxes in GDP during Obama’s term, especially from FY2010 onwards.

C. Do Lower Taxes Lead to Faster Growth in GDP or Jobs?

Mitt Romney and the Republican Party leaders also repeatedly assert that cuts in taxes, including on the rich, will lead to faster growth in both output (GDP) and jobs. The super-rich now have the new name of “job creators”. But is there any historical evidence to support this?

The following table shows for the US by decade, since the 1960s, the average collection of taxes as a share of GDP, growth in GDP and in jobs over the decade, and the average highest tax bracket on ordinary income in the tax code (the rate the super-rich will pay on ordinary income) in the decade:

| Taxes/GDP Period Avg | GDP Growth Rate | Jobs Growth Rate | Highest Tax Bracket – Period Avg | |

| 1961-1970 | 18.0% | 4.3% | 2.8% | 78.4% |

| 1971-1980 | 17.9% | 3.2% | 2.5% | 70.0% |

| 1981-1990 | 18.2% | 3.2% | 1.8% | 44.2% |

| 1991-2000 | 18.8% | 3.3% | 2.0% | 37.9% |

| 2001-2010 | 17.1% | 1.6% | -0.2% | 35.8% |

| Bush term: | ||||

| 2001-08 | 17.6% | 2.2% | 0.2% | 36.0% |

Sources: Taxes/GDP and GDP growth calculated from OMB Historical Tables; Job growth from Bureau of Labor Statistics; and Highest tax bracket from Tax Policy Center.

Taxes as a share of GDP did come down, and were at their lowest of any decade, in the 2001-2010 period. The decade average for the highest tax bracket was also the lowest. But while GDP grew by between 3.2% and 4.3% a year in the preceding four decades, growth fell to just 1.6% a year in the decade with the lowest taxes. Job growth was between 1.8% and 2.8% a year in the preceding four decades, but fell to a negative 0.2% when taxes on the “job creators” were at their lowest. The bottom line of the table also shows the figures for just the Bush term of 2001 to 2008, before the full effects of the 2008 downturn were felt, to show that these results are not simply a consequence of the downturn in the final years of the decade, weighing down the decade long results.

Such a comparison across periods is simplistic, of course. There is much else going on. But there is no evidence here that the Bush tax cuts, and the recent tax cuts keeping taxes low, have led to a long-term structural rise in the growth rate of the economy, or of the jobs being generated. The evidence that exists is completely inconsistent with this, and indeed by itself it consistent with the opposite.

D. Conclusion

To summarize:

1) Taxes as a share of GDP are now at record lows, and have been since Obama took office.

2) Other than in FY2009, when the economy was at its trough following the 2008 collapse, the record low share of taxes as a share of GDP has been largely due to a series of very large tax cuts signed by Obama. That is, the shares of taxes have remained at record lows largely due to policy, and not due to the weak economy.

3) There is no evidence from US history of the past half century which would suggest that lower tax collections or a lower tax bracket for the super-rich will lead to a higher growth rate for the economy or for jobs. In fact, the downward trend in taxes since the Bush tax cuts of 2001 and 2003 has been associated with the lowest decade long growth rates of GDP or jobs of the past half century.

A previous posting on this blog showed that the US public debt problem (with a rising public debt to GDP ratio) is fully due to the impact of the Bush tax cuts. That blog posting showed that simply be phasing out the Bush tax cuts from 2014 onwards, the public debt to GDP ratio would be brought back down over time, rather than grow explosively (if there is no change to current policy). The Bush tax cuts by themselves account for the US fiscal problems of at least the next decade.

With record low tax collection as a share of GDP, with the downward trend in tax collection a consequence of the Bush tax cuts of 2001 and 2003, with subsequent extensions of these tax cuts signed by Obama along with other major tax cuts passed as part of the stimulus package and in payroll taxes leading to record low tax collections in the US as a share of GDP, and with no evidence that the lower taxes of the past decade have led to higher long term growth rates of the economy or of jobs, it is difficult to see how the current economic difficulties are due to taxes that are too high. To deal with a problem, one must first recognize its origins. The Bush tax cuts were a disaster for the economy, and restoring tax rates (over time, once the economy is in a more solid recovery) to what they were in the 1990s would solve America’s fiscal problems.

You must be logged in to post a comment.