A. Introduction

The belief that tax cuts will spur growth and new jobs, and indeed even lead to an improvement in the fiscal accounts, remains a firm part of Republican dogma. The tax plans released by the main Republican presidential candidates this year all presume, for example, that a spectacular jump in growth will keep fiscal deficits from increasing, despite sharp cuts in tax rates. And conversely, Republican dogma also holds that tax increases will kill growth and thus then lead to a worsening in the fiscal accounts. The “evidence” cited for these beliefs is the supposed strong recovery of the economy in the 1980s under Reagan.

But the facts do not back this up. There have been four major rounds of changes in the tax code since Reagan, and one can look at what happened after each. While it is overly simplistic to assign all of what followed solely to the changes in tax rates, looking at what actually happened will at least allow us to examine the assertion underlying these claims that the Reagan tax cuts led to spectacular growth.

The four major changes in the tax code were the following. While each of the laws made numerous changes in the tax code, I will focus here on the changes made in the highest marginal rate of tax on income. The so-called “supply-siders” treat the highest marginal rate to be of fundamental importance since, under their view, this will determine whether individuals will make the effort to work or not, and by how much. The four episodes were:

a) The Reagan tax cuts signed into law in August 1981, which took effect starting in 1982. The highest marginal income tax rate was reduced from 70% before to 50% from 1982 onwards. There was an additional round of tax cuts under a separate law passed in 1986, which brought this rate down further to 38.5% in 1987 and to 28% from 1988 onwards. While this could have been treated as a separate tax change episode, I have left this here as part of the Reagan legacy. Under the Republican dogma, this should have led to an additional stimulant to growth. We will see if that was the case. There was also a more minor change under George H.W. Bush as part of a 1990 budget compromise, which brought the top rate partially back from 28.0% to 31.0% effective in 1991. While famous as it went against Bush’s “read my lips” pledge, the change was relatively small.

b) The tax rate increases in the first year of the Clinton presidency. This was signed into law in August 1993, with the tax rate increases applying in that year. The top marginal income tax rate was raised to 39.6%.

c) The tax cuts in the George W. Bush presidency that brought the top rate down from 39.6% to 38.6% in 2002 and to 35.0% in 2003. The initial law was signed in June 2001, and then an additional act passed in 2003 made further tax cuts and brought forward in time tax cuts being phased in under the 2001 law.

d) The tax rate increases for those with very high incomes signed into law in December 2012, just after Obama was re-elected, that brought the marginal rate for the highest income earners back to 39.6%.

We therefore have four episodes to look at: two of tax cuts and two of tax increases. For each, I will trace what happened from when the tax law changes were signed up to the end of the administration responsible (treating Reagan and Bush I as one). The questions to address are whether the tax cut episodes led to exceptionally good job growth and GDP growth, while the the tax increases led to exceptionally poor job and GDP growth. We will then look at what happened to the fiscal accounts.

B. Jobs and GDP Growth Following the Changes in Tax Law

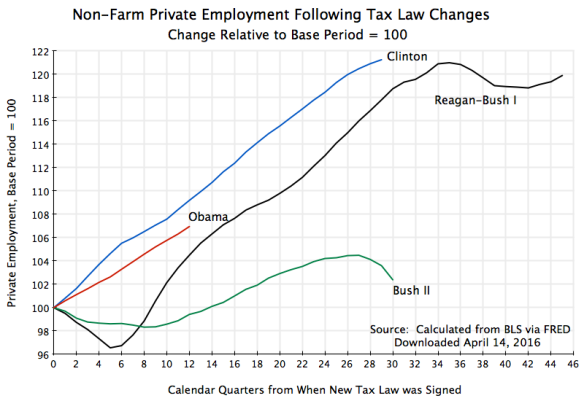

The chart at the top of this post shows what happened to private employment, by calendar quarter relative to a base = 100 for the quarter when the new law was signed. The data is from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (downloaded, for convenience, from FRED). A chart using total employment would look almost exactly the same (but one could argue that government employment should be excluded as it is driven by other factors).

As the chart shows, private job growth was best following the Clinton and Obama tax increases, was worse under Reagan-Bush I, and abysmal under Bush II. There is absolutely no indication that big tax cuts, such as those under Reagan and then Bush II, are good for job growth. I would emphasize that one should not then jump to the conclusion that tax increases are therefore good for job growth. That would be overly simplistic. But what the chart does show is that the oft-stated claim by Republican pundits that the Reagan tax cuts were wonderful for job growth simply has no basis in fact.

How about the possible impact on GDP growth? A similar chart shows (based on BEA data on the GDP accounts):

Once again, growth was best following the Clinton tax increases. Under Reagan, GDP growth first fell following the tax cuts being signed into law (as the economy moved down into a recession, which by NBER dating began almost exactly as the Reagan tax cut law was being signed), and then recovered. But the path never catches up with that followed during the Clinton years. Indeed after a partial catch-up over the initial three years (12 calendar quarters), the GDP path began to fall steadily behind the pace enjoyed under Clinton. Higher taxes under Clinton were clearly not a hindrance to growth.

The Bush II and Obama paths are quite similar, even though growth during these Obama years has had to go up against the strong headwinds of fiscal drag from government spending cuts. Federal government spending on goods and services (from the GDP accounts, with the figures in real, inflation-adjusted, terms) rose at a 4.4% per annum pace during the eight years of the Bush II administration, and rose at a 5.6% rate during Bush’s first term. Federal government spending since the late 2012 tax increases were signed under Obama have fallen, in contrast, at a 2.8% per annum rate.

There is therefore also no evidence here that tax cuts are especially good for growth and tax increases especially bad for growth. If anything, the data points the other way.

C. The Impact on the Fiscal Accounts

The argument of those favoring tax cuts goes beyond the assertion that they will be good for growth in jobs and in GDP. Some indeed go so far as to assert that the resulting stimulus to growth will be so strong that tax revenues will actually rise as a result, since while the tax rates will be lower, they will be applied against resulting higher incomes and hence “pay for themselves”. This would be nice, if true. Something for nothing. Unfortunately, it is a fairy tale.

What happened to federal income taxes following the changes in the tax rates? Using CBO data on the historical fiscal accounts:

Federal income tax revenues (in real terms) either fell or at best stagnated following the Reagan and then the Bush II tax cuts. The revenues rose following the Clinton and Obama tax increases. The impact is clear.

While one would think this should be obvious, the supply-siders who continue to dominate Republican thinking on these issues assert the opposite has been the case (and would be, going forward). Indeed, in what must be one of the worst economic forecasts ever made in recent decades by economists (and there have been many bad forecasts), analysts at the Center for Data Analysis at the conservative Heritage Foundation concluded in 2001 that the Bush II tax cuts would lead government to “effectively pay off the publicly held federal debt by FY 2010”. Publicly held federal debt would fall below 5% of GDP by FY2011 they said, and could not go any lower as some federal debt is needed for purposes such as monetary operations. But actual publicly held federal debt reached 66% of GDP that year. That is not a small difference.

Higher tax revenues help then make it possible to bring down the fiscal deficit. While the deficit will also depend on public spending, a higher revenue base, all else being equal, will lead to a lower deficit.

So what happened to the fiscal deficit following these four episodes of major tax rate changes? (Note to reader: A reduction in the fiscal deficit is shown as a positive change in the figure.)

The deficit as a share of GDP was sharply reduced under Clinton and even more so under Obama. Indeed, under Clinton the fiscal accounts moved from a deficit of 4.5% of GDP in FY1992 to a surplus of 2.3% of GDP in FY2000, an improvement of close to 7% points of GDP. And in the period since the tax increases under Obama, the deficit has been reduced by over 4% points of GDP, in just three years. This has been a very rapid base, faster than that seen even during the Clinton years. Indeed, the pace of fiscal deficit reduction has been too fast, a consequence of the federal government spending cuts discussed above. This fiscal drag held back the pace of recovery from the downturn Obama inherited in 2009, but at least the economy has recovered.

In contrast, the fiscal deficit deteriorated sharply following the Reagan tax cuts, and got especially worse following the Bush II tax cuts. The federal fiscal deficit was 2.5% of GDP in FY1981, when Reagan took office, went as high as 5.9% of GDP in FY1983, and was 4.5% of GDP in FY1992, the last year of Bush I (it was 2.5% of GDP in FY2015 under Obama). Bush II inherited the Clinton surplus when he took office, but brought this down quickly (on a path initially similar to that seen under Reagan). The deficit was then 3.1% of GDP in FY2008, the last full year when Bush II was in office, and hit 9.8% of GDP in FY2009 due largely to the collapsing economy (with Bush II in office for the first third of this fiscal year).

Republicans continue to complain of high fiscal deficits under the Democrats. But the deficits were cut sharply under the Democrats, moving all the way to a substantial surplus under Clinton. And the FY2015 deficit of 2.5% of GDP under Obama is not only far below the 9.8% deficit of FY2009, the year he took office, but is indeed lower than the deficit was in any year under Reagan and Bush I. The tax increases signed into law by Clinton and Obama certainly helped this to be achieved.

D. Conclusion

The still widespread belief among Republicans that tax cuts will spur growth in jobs and in GDP is simply not borne out be the facts. Growth was better following the tax increases of recent decades than it was following the tax cuts.

I would not conclude from this, however, that tax increases are therefore necessarily good for growth. The truth is that tax changes such as those examined here simply will not have much of an impact in one direction or the other on jobs and output, especially when a period of several years is considered. Job and output growth largely depends on other factors. Changes in marginal income tax rates simply will not matter much if at all. Economic performance was much better under the Clinton and Obama administrations not because they raised income taxes (even though they did), but because these administrations managed better a whole host of factors affecting the economy than was done under Reagan, Bush I, or Bush II.

Where the income tax rates do matter is in how much is collected in income taxes. When tax rates are raised, more is collected, and when tax rates are cut, less is collected. This, along with the management of other factors, then led to sharp reductions in the fiscal deficit under Clinton and Obama (and indeed to a significant surplus by the end of the Clinton administration), while fiscal deficits increased under Reagan, Bush I, and Bush II.

Higher tax collections when tax rates go up and lower collections when they go down should not be a surprising finding. Indeed, it should be obvious. Yet one still sees, for example in the tax plans issued by the Republican presidential candidates this year, reliance on the belief that a miraculous jump in growth will keep deficits from growing.

There is no evidence that such miracles happen.

You must be logged in to post a comment.