A. Introduction

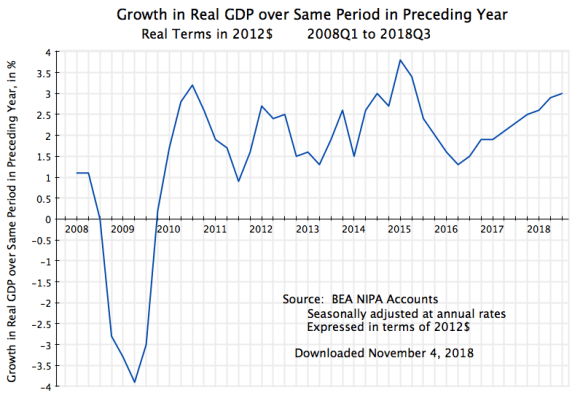

Those who follow the monthly release of the Employment Situation report of the Bureau of Labor Statistics (with the most recent issue, for April, released on May 3) may have noticed something curious. While the figures on total employment derived from the BLS survey of establishments reported strong growth, of an estimated 263,000 in April, the BLS survey of households (from which the rate of unemployment is estimated) reported that estimated employment fell by 103,000. And while there is month-to-month volatility in the figures (they are survey estimates, after all), this has now been happening for several months in a row: The establishment survey has been reporting strong growth in employment while the household survey has been reporting a fall. The one exception was for February, where the current estimate from the establishment survey is that employment grew that month by a relatively modest 56,000 (higher than the initial estimate), while the household survey reported strong growth in employment that month of 255,000.

The chart above shows this graphically, with the figures presented in terms of their change relative to where they were in April 2017, two years ago. For reasons we will discuss below, there is substantially greater volatility in the employment estimates derived from the household survey than one finds in the employment estimates derived from the establishment survey. But even accounting for this, a significant gap appears to have opened up between the estimated growth in employment derived from the two sources. Note also that the estimated labor force (derived from the household survey) has also been going down recently. The unemployment rate came down to just 3.6% in the most recent month not because estimated employment rose – it in fact fell by 103,000 workers. Rather, the measured unemployment rate came down because the labor force fell by even more (by 490,000 workers).

There are a number of reasons why the estimates from the two surveys differ, and this blog post will discuss what these are. To start, and as the BLS tries to make clear, the concept of “employment” as estimated in the establishment survey is different from that as measured in the household survey. They are measuring different, albeit close, things. But there are other factors as well.

One can, however, work out estimates where the employment concepts are defined almost, but not quite, the same. What is needed can be found in figures provided as part of the household survey. We will look at those below and present the results in a chart similar to that above, but with employment figures from the household survey data adjusted (to the extent possible) to match the employment concept of the establishment survey. But one finds that the gap that has opened up between the employment estimates of the two surveys remains, similar to that in the chart above.

There are residual differences in the two employment estimates. And they follow a systematic pattern that appear to be correlated with the unemployment rate. The final section below will look at this, and discuss what might be the cause.

The issues here are fairly technical ones, and this blog post may be of most interest to those interested in digging into the numbers and seeing what lies behind the headline figures that are the normal focus of news reports. And while a consistent discrepancy appears to have opened up between the two estimates of employment growth, the underlying cause is not clear. Nor are the implications for policy yet fully clear. But the numbers may imply that we should be paying more attention to the much slower growth in the estimates of total employment derived from the household survey, than the figures from the establishment survey that we normally focus on. We will find in coming months whether the inconsistency that has developed signals a change in the employment picture, or simply reflects unusual volatility in the underlying data.

B. The BLS Surveys of Establishments, and of Households

The monthly BLS employment report is based on findings from two monthly surveys the BLS conducts, one of establishments and a second of households. As described by the BLS in the Techincal Note that is released as part of each month’s report (and which we will draw upon here), they need both. And while the surveys cover a good deal of material other than employment and related issues, we will focus here just on the elements relevant to the employment estimates.

The establishment survey covers primarily business establishments, but also includes government agencies, non-profits, and most other entities that employ workers for a wage. However, the establishment survey does not include those employed in agriculture (for some reason, possibly some historical bureaucratic issue between agencies), as well as certain employment that can not be covered by a survey of establishments. Thus they do not cover the self-employed (if they work in an unincorporated business), nor unpaid family workers. Nor do they cover those employed directly by households (e.g. for childcare).

But for the business establishments, government agencies, and other entities that they do cover, they are thorough. They survey more than 142,000 establishments each month, covering 689,000 individual worksites, and in all cover in this “sample” approximately one-third of all nonfarm employees. This means they obtain direct figures each month on the employment of about 50 million workers (out of the approximately 150 million employed in the US), with this closer to a census than a normal sample survey. But the extensive coverage is necessary in order to be able to arrive at statistically valid sample sizes at the detailed individual industries for which they provide figures. And because of this giant sample size, the monthly employment figures cited publicly are normally taken from the establishment survey.

To arrive at unemployment rates and other figures, one must however survey households. Businesses will know who they employ, but not who is unemployed. And while the current sample size used of households is 60,000, this is far smaller relative to the sample size used for establishments (142,000) than it might appear. A household will in general have just one or two workers, while a business establishment (or a government agency) could employ thousands.

Thus the much greater volatility seen in the employment estimates from the household survey should not be a surprise. But they need the household survey to determine who is in the labor force. They define this to be those adults of age 16 or older, who are either employed (even for just one hour, if paid) in the preceding week, or who, if not employed, were available for a job and were actively searching for one at some point in the four week period before the week of the survey. Only in this way can the BLS determine the share of the labor force that is employed, and the share unemployed. The survey of establishments by its nature cannot provide such information no matter what its sample size.

For this and other reasons, the definition of what is covered in “employment” between these two surveys will differ. In particular:

a) As discussed above, the establishment survey does not cover employment in the agricultural sector. While they could, in principle, include agriculture, for some reason they do not. The household survey does include those in agriculture.

b) The establishment survey also does not include the self-employed (unless they are running an incorporated business). They only survey businesses (or government agencies and non-profits), and hence cannot capture those who are self-employed.

c) The establishment survey also does not capture unpaid family workers. The household survey counts them as part of the labor force and employed if they worked in the family business 15 hours or more in the week preceding the survey.

d) The establishment survey, since it does not cover households, cannot include private household workers (such as those providing childcare services). The household survey does.

e) Each of the above will lead to the count in the household survey of those employed being higher than what is counted in the establishment survey. Working in the opposite direction, someone holding two or more jobs will be counted in the establishment survey two or more times (once for each job they hold). The establishment being surveyed will only know who is working for them, and not whether they are also working elsewhere. The household survey, however, will count such a worker as just one employed person.

f) The household survey also counts as employed those who are on unpaid leave (such as maternity leave). The establishment survey does not (although it is not clear to me why they couldn’t – it would improve comparability if they would).

g) The household survey also only includes those aged 16 or older as possibly in the labor force and employed. The establishment survey covers all its workers, whatever their age.

There are therefore important differences between the two surveys as to who is covered in the figures provided for “total employment”. And while the BLS tries to make this clear, the differences are often ignored in references by, for example, the news media. One can, however, adjust for most, but not all, of these differences. The data required are provided in the BLS monthly report (for recent months), or online (for the complete series). But how to do so is not made obvious, as the data series required are scattered across several different tables in the report.

I will discuss in more detail in the next section below what I did to adjust the household survey figures to the employment concept as used in the establishment survey. Adjustments could be made for each of the categories (a) through (e) in the list above, but was not possible for (f) and (g). However, the latter are relatively small, with the residual difference following an interesting pattern that we will examine.

When those adjustments are made, the number of employed as estimated from the household survey, but reflecting (almost) the concept as estimated in the establishment survey, looks as follows:

While there are some differences between the estimates here and those in the chart at the top of this post of employment made using the household survey (as adjusted), the basic pattern remains. While employment as estimated from the household survey (and excluding those in agriculture, the self-employed, unpaid family workers, household employees, and adjusted for multiple jobholders) is now growing, it was growing over the last half year at a much slower pace than what the establishment survey suggests.

C. Adjustments Made to the Employment Estimates So They Will Reflect Similar Concepts

As noted above, adjustments were made to the employment figures to bring the two concepts of the different surveys into line with each other, to the extent possible. While in principle one could have adjusted either, I chose to adjust the employment concept of the household survey to reflect the more narrow employment concept of the establishment survey. This was because the underlying data needed to make the adjustments all came from the household survey, and it was better to keep the figures for the adjustments to be made all from the same source.

Adjustments could be made to reflect each of the issues listed above in (a) through (e), but not for (f) or (g). But there were still some issues among the (a) through (e) adjustments. Specifically:

1) I sought to work out the series going back to January 1980, in order to capture several business cycles, but not all of the data required went back that far. Specifically, the series on those holding multiple jobs started only in January 1994, and the series on household employees only started in January 2000.

2) I also worked, to the extent possible, with the seasonally adjusted figures (for the establishment survey figures as well as those from the household survey). However, the figures on unpaid family workers and of household employees were only available without seasonal adjustment. I was therefore forced to use these. But since the numbers in these categories are quite small relative to the overall number employed, one does not see a noticeable difference in the graphs.

One can then compare, as a ratio, the figures for total employment as adjusted from the household survey to those from the establishment survey. The ratio will equal 1.0 when the figures are the same. This was done in steps (depending on how far back one could go with the data), with the result:

The curve in black, which can go back all the way to 1980, shows the ratio when the employment figure in the household survey is adjusted by taking out those who are self-employed (in unincorporated businesses) and those employed in agriculture. The curve in blue, from 1994 onwards, then adds in one job for each of those holding multiple jobs. The assumption being made is that those with multiple jobs almost always have two jobs. The establishment survey would count these as two employees (at two different establishments), while the household survey will only count these as one person (holding more than one job). Therefore adding a count of one for each person holding multiple jobs will bring the employment concepts used in the two surveys into alignment (and on the basis used in the establishment survey).

Finally, the curve in red subtracts out unpaid family workers in non-agricultural sectors (as those in the agricultural sector will have already been taken out when total employees in agriculture were subtracted), plus subtracts out household employees. Neither of these series are available in seasonally adjusted form, but they are small relative to total employment, so this makes little difference.

What is interesting is that even with all these adjustments, the ratio of the adjusted figures for employment from the household survey to those from the establishment survey follows a regular pattern. The ratio is low when unemployment was low (as it was in 2000, at the end of the Clinton administration, and to a lesser extent now). And it is high when unemployment was high, such as in mid-1980s during the Reagan administration (with a downturn that started in 1982) and again during the downturn of 2008/09 that began at the end of the Bush administration, with unemployment then peaking in 2010 before it started its steady recovery.

Keep in mind that the relative difference in the employment figures between the household survey (as adjusted) and the establishment survey are not large: about 1% now and a peak of about 3% in 2009/10. But there is a consistent difference.

Why? In part there are still two categories of workers where we had no estimates available to adjust the figures from the household survey to align them with the employment concept of the establishment survey: for those on unpaid leave (who are included as “employed” in the household survey but not in the establishment survey), and for those under age 16 who are working (who are not counted in the household survey but are counted as employees in the establishment survey).

These two categories of workers might account for the difference, but we do not know whether they will fully account for the difference as we have no estimates. A more interesting question is whether these two categories might account for the correlation observed with unemployment. We could speculate that during periods of high unemployment (such as 2009/10), those taking unpaid leave might be relatively high (thus bumping up the ratio), and that those under age 16 may find it particularly hard, relative to others, to find jobs when unemployment is high (as employers can easily higher older workers then, with this then also bumping up the ratio relative to times when overall unemployment is low). But this would just be speculation, and indeed more like an ex-post rationalization of what is observed than an explanation.

Still, despite the statistical noise seen in the chart, the basic pattern is clear. And that is of a ratio that goes up and down with unemployment. But it is not large. Based on the change in the ratio observed from May 2010 to April 2011 (using a 12 month average to smooth out the monthly fluctuations), to the average over May 2018 to April 2019, the monthly divergence in the employment growth figures would only be 23,000 workers. That is, the unexplained residual difference in recent years between the growth in employment (as estimated by the household survey and as estimated by the establishment survey) would be about 23,000 jobs per month.

But the differences in the estimates for the monthly change in employment between the (adjusted) series from the household survey and that from the establishment survey are much more. Between October 2018 and April 2019, employment in the adjusted household survey series grew by 65,000 per month on average. In the establishment survey series the growth was 207,000 per month. The difference (142,000) is much greater than the 23,000 that can be explained by whatever has been driving down the ratio between the two series since 2010 as unemployment has come down. Or put another way, the 65,000 figure can be increased by 23,000 per month to 88,000 per month, from adding in the unexplained residual change we observe in the ratio between the two series in recent years. That 88,000 increase in employment per month from the (adjusted) household survey figures is substantially less than the 207,000 per month figure found in the establishment survey.

D. Conclusion

Due to the statistical noise in the employment estimates of the household series, one has to be extremely cautious in drawing any conclusions. While a gap has opened up in the last half year between the growth in the employment estimates of the household survey and those of the establishment survey, it is still early to say whether that gap reflects something significant or not.

The gap is especially large if one just looks at the “employment” figures as published. Employment as recorded in the household survey has fallen between December 2018 and now, and has been essentially flat since October. But the total employment concepts between the two surveys differ, so such a direct comparison is not terribly meaningful. However, if the figures from the household survey are adjusted (to the extent possible) to match the employment concept of the business survey, there is still a large difference. Employment (under this concept) grew by 207,000 per month in the establishment survey, but by just 88,000 per month in the adjusted household survey figures.

Whether this difference is significant is not yet clear, due to the statistical noise in the household survey figures. But it might be a sign that employment growth has been less than the headline figures from the establishment survey suggest. We will see in coming months whether this pattern continues, or whether one series starts tracking the other more closely (and if so, which to which).

You must be logged in to post a comment.