Update, March 28, 2025: The BEA released on March 27 its initial estimate of GDP as measured from wage and profit income for the fourth quarter of 2024. The BEA labels this, to avoid confusion, Gross Domestic Income – GDI. In principle, it should be the same as GDP but will differ as data from different sources are used to estimate both; see the discussion in the post below. The BEA also released its initial estimate for the fourth quarter of 2024 of value-added produced by sector, from which one can calculate growth in production by private industries and in production by government. The two together sum to GDP. Charts 1 and 3 in the post and related text have been updated to reflect these new estimates.

Economic growth was strong in the last quarter of 2024 – the last full quarter of the Biden administration. Real GDP grew at a 2.4% annual pace when estimated from demand-side measures, and at a substantially faster 4.5% pace when estimated from income-side measures (i.e. GDI). Growth in the average of the two measures – GDI and GDP – was 3.5%. This is exceptionally strong. And price inflation was modest, with growth in the Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE) price deflator of 2.4% at an annual rate, and 2.6% in the core PCE price deflator.

Along with an unemployment rate of just 4.0% (as of January), Trump has inherited an extremely strong economy from Biden. We will now see what develops.

A. Introduction

On February 28, Elon Musk posted on his social media site X the comment:

“A more accurate measure of GDP would exclude government spending.

Otherwise, you can scale GDP artificially high by spending money on things that don’t make people’s lives better.”

Two days later, on March 2, Secretary of Commerce Howard Lutnick followed up on this and said in an interview on Fox News:

“You know that governments historically have messed with GDP. They count government spending as part of GDP. So I’m going to separate those two and make it transparent.”

These statements reveal a lack of understanding of what GDP means by two of the most prominent officials (or in Musk’s case, a non-official official) in the Trump administration – both key players on economic issues. While that lack of understanding is not surprising – how GDP is defined is a technical issue – what is worrying is that these prominent Trump appointees would assert this with confidence and without bothering to check first with experts whether it was in fact true. Such arrogance is unfortunately now the norm in this administration.

Lutnick’s assertion that “governments have historically messed with GDP” (in fact they have not) is also worrisome as it looks like preparation for the Trump administration to do precisely that. GDP estimates are prepared by the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA), a bureau in the Department of Commerce now headed by Lutnick. Also, just a few days before his confused statement on GDP Lutnick disbanded the standing external technical advisory committee that advised the BEA on how GDP estimates might be improved. Committee members were professionals at universities and in industry who were specialists on these issues. They were not paid and only had their travel costs covered when meetings were called. At the same time, Lutnick also disbanded several similar committees of unpaid specialists advising the Census Bureau – also part of the Department of Commerce.

The concern is that Lutnick is setting things up precisely to “mess with” how GDP is estimated. The concern is that he could very well order the BEA to manipulate the standard methodology and estimation process to come up with figures that make it look like the economy is in less trouble than it in fact is in the coming years of Trump’s second presidential term.

Musk and Lutnick do not appear to realize that GDP – which stands for Gross Domestic Product – is a measure of the market value of all the economy produces in a given period (normally expressed in annualized terms). Gross Domestic Product is a measure of production; production that takes place domestically (i.e. within the nation’s borders); and in gross terms (meaning without depreciation of capital taken out). The BEA also produces estimates with depreciation subtracted – which it calls Net Domestic Product or NDP – but less attention is paid to those figures as depreciation is especially hard to estimate, both conceptually and in practice.

The aim of the GDP measure is thus to arrive at an estimate of how much the nation’s economy is producing. How that production is used is not the purpose of the measure, and there is no assessment of whether that use should be considered “good” or “not so good”. But it is disparaging to assert (as Musk and Lutnick have) that the services that the government provides – such as the services of the school teacher pictured above – are worthless and hence should not be counted.

Those statements of Musk and Lutnick do, however, provide a “teachable moment”. Many others – including some in the news media – are also confused about what GDP means and signifies. This post will seek to sort through those confusions. The first section below will review what GDP means and how it is estimated. Those are two separate things. Lutnick and Musk are conflating what GDP is designed to measure (i.e. production) with one way in which GDP may be estimated (from the demand side, by estimating how that production is used). The BEA in fact estimates GDP in three different ways, with this serving to provide also cross-checks on the estimates. In principle, GDP as estimated by each of the three methods should be the same. But one is dealing with real-world data, there will always be statistical noise, and hence by using three different approaches the BEA can arrive at a more robust overall estimate.

Lutnick also asserted there is a lack of transparency in the GDP figures, in that the BEA includes figures on government spending in GDP. This is confused and it is also defamatory to assert that the BEA is anything other than transparent. The BEA issues each month regularly updated figures not just on GDP but also on much else in what is more formally called the National Income and Product Accounts (NIPA). In these, the BEA provides estimates on all sorts of aggregates with and without government spending. While Lutnick and Musk are not clear about what they are seeking, one guess is that they are looking for a figure on domestic production that excludes whatever is produced directly by government (such as the services of the public school teacher pictured above). But the BEA in fact provides this: It is called Value-Added by Private Industries. The BEA provides estimates of this for each calendar quarter and in both real and nominal terms. Charts below will show (using the published BEA figures) what growth would have been whether measured by GDP as defined or by a measure of growth that excludes government-produced services.

We will also look at some simple measures of the productivity of federal government workers over time. The calculations are of necessity rough, but if one counts only the management of federal discretionary expenditures, the growth in federal worker productivity in fact matched (over the period 1997 to 2023) the growth in overall labor productivity in the economy. And if one includes also the management of mandatory spending (entitlement programs such as Social Security and Medicare), federal worker productivity has grown far faster than overall labor productivity in the economy. These estimates should not be taken too seriously, as there is no way to assess how well-managed the programs are. But in simple but crude terms, there is no evidence that growth in federal worker productivity has lagged what the rest of the economy has achieved. Indeed, by one measure it was far better.

The post will end with some final comments. While I am sure Musk and Lutnick do not realize it, their notion of what GDP should and should not include is in many respects similar to concepts used in the Material Balances System of national accounts (also called the Material Product System) developed in the 1930s by Gosplan in Stalin’s USSR. It was then used (by command – there was no choice here) in the communist countries of Eastern Europe up until 1990. Those systems excluded the concept of certain services as contributing to production, similar to what Musk and Lutnick are advocating now. It was built on the concept from Karl Marx of productive and unproductive labor, with Musk and Lutnick asserting that certain labor (those employed in government) is unproductive.

It is ironic that senior figures in the Trump administration appear to be advocating for a system similar in nature to that developed in Stalin’s USSR. We know that that did not end well.

B. The Meaning of GDP versus How GDP is Estimated

GDP – Gross Domestic Product – is a measure of the market value of what the economy is producing. That is not the same concept as what the economy is using. While statisticians can make use of data on how output is being used in order to arrive at an estimate of what was produced, confusion on this point appears to have led to the error Musk and Lutnick made. While what they did mean is not fully clear, they mistakenly asserted that eliminating one of the uses of output (that by government) would yield “a more accurate measure of GDP” (as Musk put it in the quote above). That is not correct. It would no longer be GDP.

The confusion – which others have made as well – stems from how GDP is estimated. The BEA (and also the international standard on national account concepts) estimates GDP in three different ways. The three should in principle yield the same figure for GDP (after some minor adjustments to reflect indirect taxes and subsidies). But with real-world data, the three estimates will normally differ only by some – hopefully small – amount. The three approaches will serve, however, as cross-checks on each other, and can flag that there is an issue if one of the estimates differs significantly from the others.

An earlier post on this blog discussed those three methods for estimating GDP. Readers may wish to read that post (which covers also how recessions are identified and formally declared) for a more complete discussion. And for a much more detailed review, they may refer to Chapter 2 of the NIPA Handbook issued by the BEA. But briefly, GDP is estimated by:

a) The initial, and most widely viewed, estimate of GDP comes not from estimates of what is produced, but rather from how that production is used. As those who have studied any economics know, GDP will be equal to the sum of Personal Consumption, Private Investment, Government Consumption and Investment, and Net Exports (i.e. Exports less Imports). This holds not because Personal Consumption and the other uses of GDP are themselves producers of GDP (although some commentators often imply that), but rather because Private Investment includes investment in inventory accumulation. Whatever is produced and not sold will accumulate in inventories, and with this as a balancing item one can go from the sum of all the uses of output to what production itself was.

It is a simple trick, but often misunderstood. It allows the BEA to arrive at a fairly good estimate of how much production (GDP) grew in any calendar quarter just one month after the end of each quarter. The BEA formally calls this its “Advance Estimate” of GDP, although many refer to it as the first or initial estimate of GDP. It is then revised a month later (to produce the “Second Estimate”), and again a month after that (to produce the “Third Estimate”), as more complete data become available to the BEA.

The components of demand are also interesting and important in themselves. They provide figures on what happened to personal consumption, fixed as well as inventory investment, and the other demand components of GDP. To many, these figures on spending are of more interest than what happened in a particular sector of production. And perhaps more importantly, in a modern economy production itself is largely driven by what producers can sell. As Keynes taught us, production cannot be taken as a given at some “full employment” level, but rather will respond to what producers believe they can sell at a price that will cover their costs.

If, as Musk and Lutnick appear to be saying (again, they are not fully clear), the use of production by government (or some portion of that use) were to be subtracted from GDP, then the sum of what is used in the economy will no longer match what is produced by the economy. That simple identity will no longer hold.

b) GDP is also estimated by summing up the incomes (wages and profits) generated by the act of production. This is based primarily on data obtained by the BLS from its monthly survey of business establishments (the Current Employment Statistics – or CES – survey; most commonly known for the monthly employment estimates it provides); from the Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages (QCEW) also of the BLS and with more detail on earnings; from the Quarterly Financial Report (QFR) of the Census Bureau (that obtains, for a sample of business firms, statistics on their financial positions and profits); and from a range of other sources to fill in the gaps (e.g. on farm incomes).

The value of all that is produced in the economy will accrue as someone’s income. Thus by arriving at an estimate of aggregate incomes, the BEA will have a second approach to estimating GDP. Those incomes include wages and other compensation paid to labor (e.g. health insurance, pension contributions, and such) plus the profits (or gross margin) accruing to the owners of the firms. Since GDP is a gross concept (meaning before any deduction for depreciation of capital), the profit concept will be profits before any deduction for depreciation allowances.

The BEA does not try to provide an estimate of GDP by this approach in its Advance (first) Estimate of GDP released one month after the end of each quarter. It does not yet have sufficient data to do this. Rather, its first estimate is only (normally) provided with its Second Estimate of the GDP accounts two months after the end of each quarter. At that time it issues a revised estimate of its demand-side estimate of GDP, and its initial estimate of GDP as arrived at from its income-side figures. To avoid confusion, it calls this estimate Gross Domestic Income (GDI) rather than GDP, although in principle they should be the same. But in the real world, the GDP and GDI figures will differ by some (hopefully small) amount, and to be fully transparent, the BEA shows this difference with the label of “Statistical Discrepancy”. The BEA also provides a figure for the simple average of the GDP (demand-side) and GDI (income-side) estimates. Many professionals take the quarterly changes in that simple average to be a better estimate of what growth has been in the economy – better than either GDP or GDI alone.

[Side note: The initial GDI estimates are normally provided at the time of the Second Estimate of the GDP accounts, i.e. two months following the end of each quarter. But the figures for the fourth quarter of the year are an exception, as extra time is allowed for businesses to complete their end-of-year accounting. Thus the initial GDI estimates for the fourth quarter of each year are not released in late February but rather in late March.]

It is not clear what would happen to this GDI estimate should the BEA be required by Lutnick (its boss) to not count government spending (or some portion of government spending) in its GDP estimates. Not only do government workers (civil servants) earn incomes, but wages are paid and profits are earned on the production of what government purchases. While it would be straightforward (although silly) to exclude wages earned by government workers from the total incomes earned in society, it would be far more difficult to try to cancel out wages and profits earned on production sold to government. But unless one did that, GDI would no longer match up with the concept of GDP that Musk and Lutnick appear to be calling for.

c) The third approach the BEA uses to estimate GDP is to estimate directly what each sector in the economy produces and then add it up. This is, however, the most difficult. Hence the initial estimate of GDP in this way is not issued until the third month following the end of each calendar quarter (at which time the BEA issues also a second set of revised estimates of GDP from the demand side and a first set of revised estimates of GDP from the income side (i.e. GDI). And while in principle this direct production-side estimate of GDP should match the other two estimates of GDP, the BEA does not publish what they arrived at for overall GDP from that production-side estimate. Rather, for whatever reason (possibly limited confidence in the adequacy of the data they have at the time, or to avoid confusion by the public) the BEA scales their sector-by-sector estimates of production to match their (twice-revised) demand-side estimate of GDP.

To avoid double-counting, only the value that is added in each sector is counted (“value-added”). The value-added in a sector of production is the gross revenues from the sale of what is produced minus what that sector purchases from other sectors – which are called intermediate inputs. Thus, for example, the value-added of a bakery will equal the revenues of the bread that it sells less the cost of the inputs it had purchased – the flour, energy, water, and other ingredients it used. A portion of that value-added is paid to the workers in wages and other compensation, and what is left is the gross margin or profits (the BEA uses the term “gross operating surplus”) of the bakery. And for Gross Domestic Product (as opposed to Net National Product), it will be the profits before any deduction for depreciation.

Adding up value-added across all sectors of the economy should then match GDP as estimated from the demand side and GDP (GDI) as estimated from the income side. But a question that then arises is how do they estimate value-added by the part of government that does not sell its output on the market? While government enterprises (such as the Post Office, government-owned public utilities such as water companies, certain toll roads, and similarly) are an exception, they are a relatively small share of what government does. A similar issue arises for non-profits who do not sell what they provide.

For what is called “general government” (government excluding government enterprises), as well as non-profits who do not sell what they provide on the market, the BEA follows standard international guidelines and sets the value-added of such entities to equal what it pays in wages and other compensation to government workers plus an estimate of what depreciation was on the capital assets of the government (or the non-profits). The estimated depreciation is added in order to make these figures comparable to the figures for value-added in the sectors where goods and services are sold in the market.

Adding value-added estimated in this way for general government (and non-profits) to the figures for value-added in the sectors of the economy that sell in the markets (including by government enterprises), will then yield an estimate for GDP that in principle will match both GDP as estimated from the demand side (how the production was used, including for any inventory accumulation) and from the income side (wages and profits).

A generous interpretation of the comments of Musk and Lutnick is that they would exclude the counting of any value from the services that government itself provides when measured in the way described above. That does not appear to be the case, but it is a possible interpretation and would indeed make more sense than excluding government spending (or some portion of government spending) from the demand side estimate of GDP. That is, under this interpretation of Musk and Lutnick, the BEA would be instructed to provide an estimate of all that is produced in the economy excluding that provided by government.

But the BEA already publishes precisely such a figure. It is the sum of value-added across all of the private sectors of the economy (which the BEA labels “Private Industries”). Quarterly estimates on this are provided in the table titled “Gross Domestic Product by Industry Group” which is part of their publication of the Third Estimates of GDP, released three months following the end of each quarter. The contribution to GDP from Private Industries plus the contribution from Government sums to their overall estimate of GDP. The BEA is fully transparent on this.

What difference would it make if we assume Musk and Lutnick are referring to this concept of production as a measure of how the economy is performing? The next section will examine this.

C. Growth in GDP Compared to Growth in Private Production

How much would growth differ if it were measured based on the figures the BEA provides (and has been providing for many years) on private production as opposed to GDP? There would be some difference, but not all that much. What may be interesting is that, at least during recent presidential terms, growth in private production has been consistently higher than growth in overall GDP – although not by a substantial amount. That is, growth in government production has been kept constrained through tight budgets, which has kept overall GDP growth below the growth in private production. This is the opposite of the assertions of Musk and Lutnick that government spending has been some kind of artificial boost to the recorded figures on GDP growth.

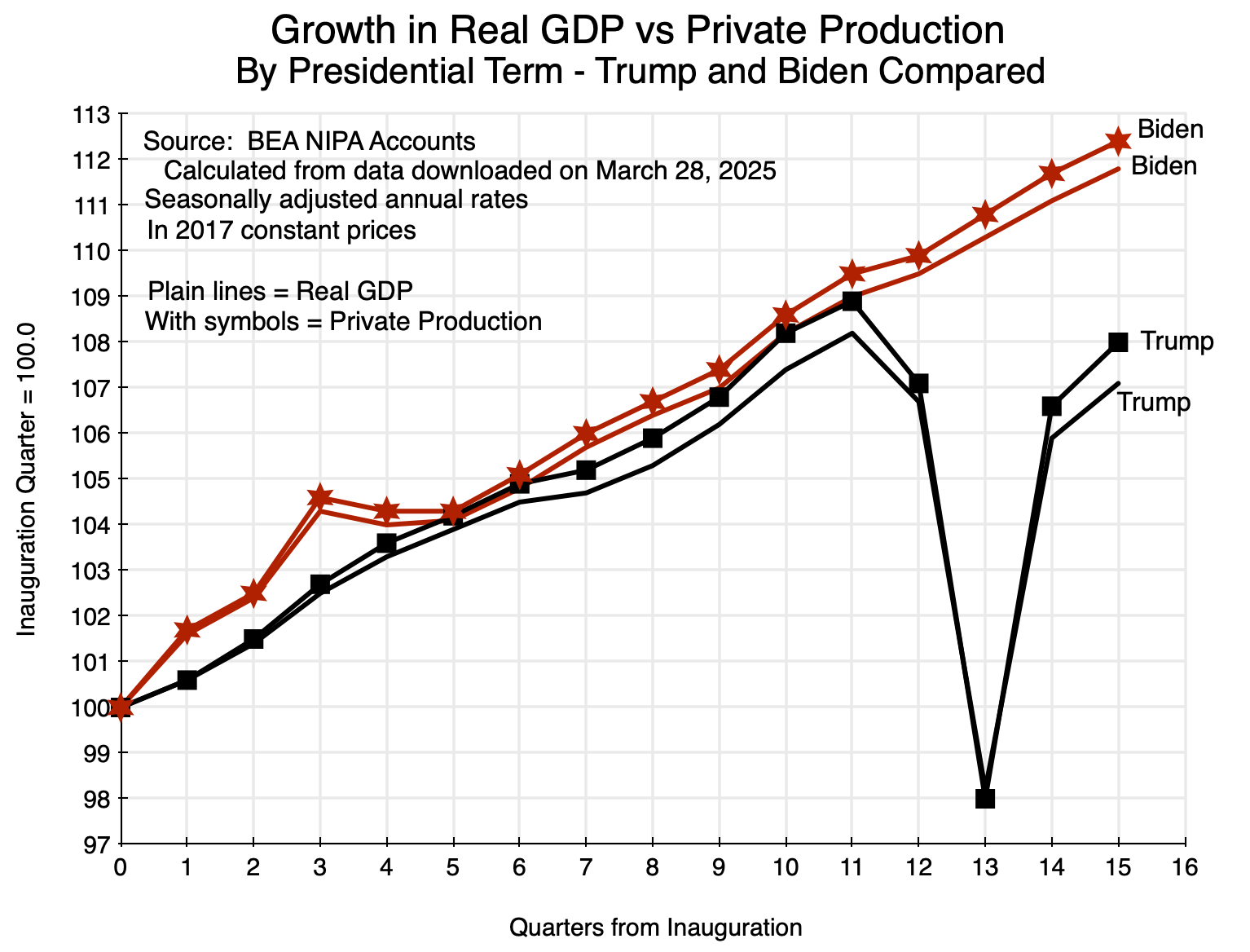

It is interesting to compare the figures on growth by presidential term. Comparing that under Biden and in Trump’s first term:

Chart 1

The plain lines show the levels of real GDP compared to what it was in the first quarter of each presidential term, while the lines of the same color but with symbols show what real growth was in private production (what the BEA labels Private Industries). Private production was consistently somewhat higher, although not by much. In terms of growth rates, real GDP grew at a 1.7% rate during Trump’s first term and at a rate of 2.8% during Biden’s. Growth in 2020 was hurt, of course, due to the Covid crisis, and Trump’s mismanagement of the crisis made it worse than it would have been. Private production grew at a faster rate for both presidents: at a 1.9% rate under Trump and a substantially higher 3.0% rate under Biden.

One can draw a similar chart for Obama’s two terms in office:

Chart 2

The same pattern holds, with growth in private production faster than the growth in GDP as a whole. The four-year growth rates were 1.8% and 2.25% for GDP in Obama’s two terms, and 2.1% and 2.5% for private production.

Since GDP is the sum of output of private industries and of government (both in value-added terms, as discussed in Section B above), the implication is that the growth in government value-added was slower than the growth in private value-added in each of these four presidential terms. This is not surprising, as government growth has been kept constrained by tight budgets limiting what government was allowed to do.

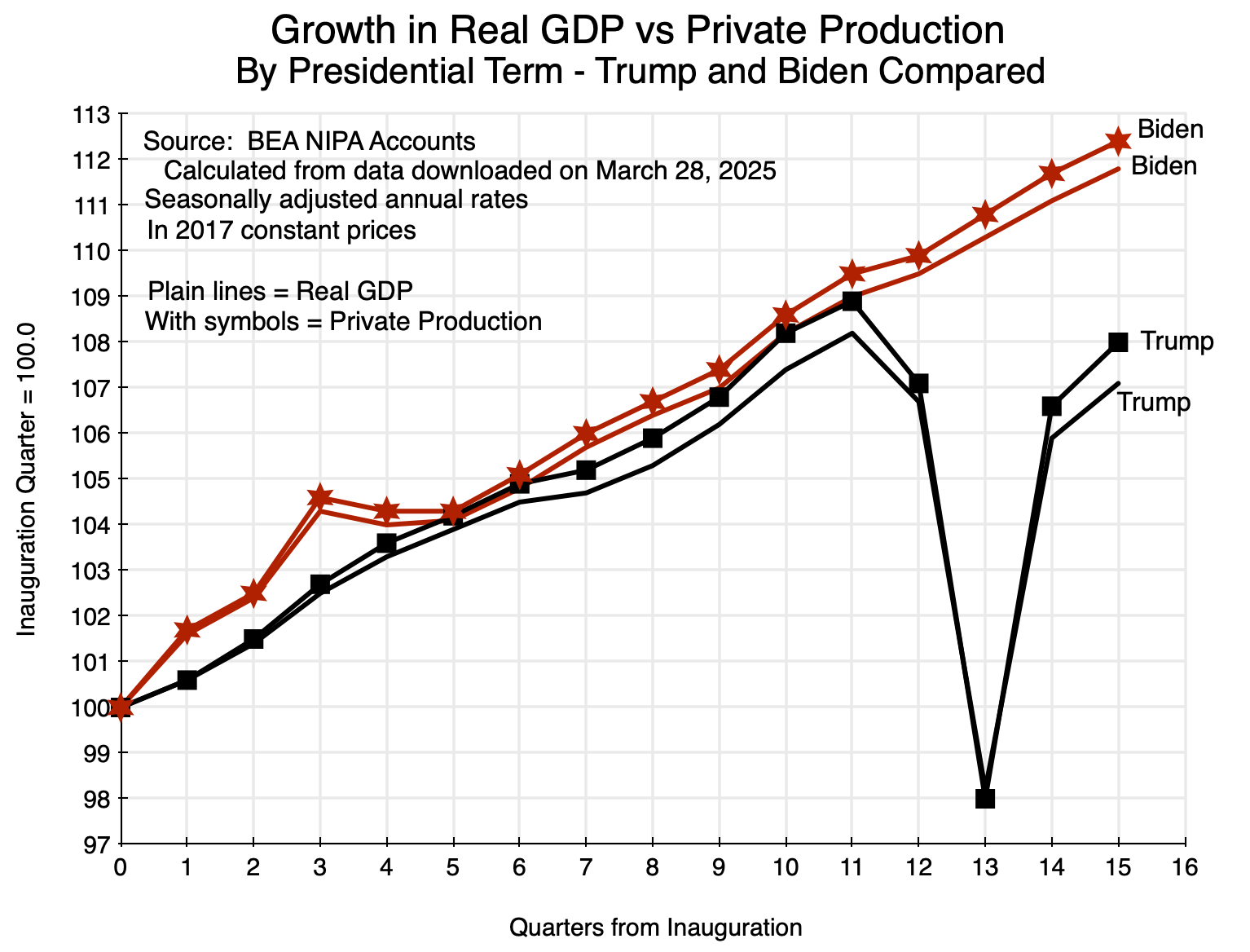

Presidents – together with Congress – are responsible for government spending at the federal level. Examining this, growth in federal government production (in value-added terms) was indeed flat or modest in each of the terms of Biden and Obama. But it grew quickly under Trump:

Chart 3

Note that this federal production under Trump was already growing rapidly well before the start of the special programs passed by Congress in response to the Covid crisis. Those special programs began only in the second quarter of 2020 – quarter #13 of his term in office. They were also largely transfer programs, and hence separate from what would be counted in government value-added. They do not explain the rapid growth in government during Trump’s first term in office, in contrast to the only modest growth, or even zero growth (in Obama’s second term), in federal programs when the Democrats were in office.

With this growth in federal production under Trump, why do we still see a substantially greater growth in private production than in overall GDP during Trump’s term (Chart 1 above)? The reason is that government value-added as a component of GDP will include not only production by the federal government, but also production by state and local governments. Furthermore, state and local level government production accounts for about two-thirds (68% in 2023) of overall government production (in value-added terms) in the US. Federal programs account only for one-third. And value-added in the state and local government sector fell at a 0.5% annual rate during Trump’s term in office, thus holding down overall government value-added despite the sharp rise in federal spending under Trump.

D. Growth in Federal Worker Productivity Over Time

Musk and Lutnick also assert that government civil servants are unproductive whose contribution should not be counted in GDP. It is, however, difficult to come up with a good measure of their contribution. What metric would one use?

While it is difficult to come up with some absolute measure, one can conceive of a measure of the efficiency with which civil servants have, over time, managed their basic work. Most of the work of federal civil servants is in the management and oversight of government-funded contracts or of federal transfer programs. Examples of the first (discretionary government spending) include the management of contracts for medical research, or to buy tanks and planes for the military, or via state and local governments for the building of public infrastructure. Examples of the second (mandatory government spending) include Social Security and Medicare.

There will be a dollar value associated with all such programs. A crude measure of growth in federal government worker productivity would be how the dollar value of the contracts they have managed has changed over time – in real terms – per federal worker. Relative to 1997 (the earliest year possible with a consistent series for all the data required), federal spending (in real terms) managed per federal worker has increased substantially:

Chart 4

Two curves are shown for federal government spending per federal worker (where only federal civilian workers are included; active duty military is excluded). One counts discretionary government spending only, and excludes mandatory spending (for programs such as Social Security and Medicare) as well as interest on government debt and wages of the federal workers themselves. This curve is shown here in blue. While there have been substantial fluctuations, as of 2023 it was almost 50% higher than what it was in 1997. And as of 2023, the increase was almost exactly the same as the increase in productivity for the economy as a whole, i.e. of real GDP per worker.

An alternative measure would include federal spending on mandatory programs in addition to spending on discretionary programs. These are highly efficient programs, with administrative spending by government entities far below what is seen at private entities managing similar programs. As was shown in an earlier post on this blog, the administrative cost of private health insurance is on average five times more expensive than the administrative cost for Medicare health insurance. And administrative costs paid on an average 401(k) retirement accounts are more than an order of magnitude higher than the administrative costs of the Social Security system. As discussed in another earlier post on this blog, the administrative costs of managing the Social Security system are only 0.5% of the benefits paid out each year. In contrast, the annual cost of the fees paid out to private accounting and financial institutions on a 401(k) is generally between 2 and 3% of the outstanding balance in the 401(k) account. The government designed programs are large, simple, and far more efficiently managed than private programs for similar matters.

Including these (and other) mandatory federal programs along with federal discretionary spending, the dollar values of the spending managed per federal worker doubled between 1997 and 2023 (see Chart 4). This was far greater than the almost 50% increase in real GDP per worker in the economy as a whole. It spiked even higher in 2020 and 2021 due to the massive Covid relief programs of those years.

This metric cannot assess how well federal workers are managing these programs in absolute terms. But in terms of the effectiveness (in dollar costs per federal worker) with which they are being managed, federal worker productivity has grown substantially over the past quarter century.

E. Concluding Comments – Similarities with the Material Product System of National Accounts of the USSR

While I am pretty sure Musk and Lutnick did not have it in mind when they asserted that “GDP” would be better measured by excluding the value of what government workers provide (or government spending in general), their proposal has parallels with the national accounts system developed by Gosplan in the 1930s in Stalin’s USSR. That system – called the Material Product System (or also Material Balance Planning) – placed a value only on the production of material goods and not of certain services. The concept for overall output in this system was not GDP but rather what the system defined as Net Material Product (NMP). In contrast to GDP, NMP excluded the value of what it called “non-productive” services, which in that system included government services as well as health care, education, housing, passenger (but not freight) transport, financial services, and more.

Gosplan developed their system of national accounts based on the concept from Marx of productive and unproductive labor. Only the production of material goods was viewed as productive, while labor used in the production of non-material goods was unproductive. Thus whatever was provided by the latter should be excluded from their concept of overall output – i.e. excluded from their NMP.

I doubt that Musk and Lutnick were trying to follow some version of these Marxist concepts in their assertion that “GDP” should exclude the value of what government provides. But the parallels are interesting. The Material Product System of national accounts was used in the USSR and then in the post-war period in the Communist countries of Eastern Europe until 1990. As we know, that did not end well. One of the problems was that with their system of national accounts, they did not have a good view of what was in fact happening in their economies as conditions deteriorated over the decades.

There will be basic inconsistencies as well in trying to exclude one component of GDP in the integrated NIPA accounts, claiming that government does not contribute to GDP. The three-way equality of GDP based on how production is used, the wage and profit income generated in production, and the value-added produced in all sectors of the economy, will then no longer hold.

A generous interpretation of Musk and Lutnick would be that they are calling for national income accounts that would count in GDP only the value of what is produced in private activities, i.e. excluding government. One could do this, but it would no longer be GDP. Rather, one would then have simply the sum of value-added across all private industries. But if that is what they want, the BEA already provides it.

Not understanding national income accounting is, of course, minor in comparison to what Trump and his administration have done since taking office in January. The disregard of basic laws and indeed the Constitution, the firing for no cause of thousands of civil servants and the closure of agencies established by Congress, and the vindictiveness of Trump’s attacks – and his willingness to use raw government power – on American media, universities, law firms, and individuals who have criticized him, are all of far greater consequence.

But the confident assertions of Musk and Lutnick on what should count in GDP is a further example of the self-confident arrogance of this administration.

You must be logged in to post a comment.