A pair of disappointing reports, from this morning (June 1) and yesterday (May 31), indicate that the economy continues to grow only slowly, with consequent slow growth in employment and indeed a small rise in the rate of unemployment to 8.2% from 8.1% last month. Posts on this blog in January, on GDP growth and on employment, had flagged that growth, which at that time appeared to be improving, could well fall back in 2012. Unfortunately, that appears to be happening. Cut-backs in government spending account for a major part of that disappointing growth.

The Bureau of Labor Statistics, in its June 1 release this morning on employment, found that total US employment grew in May by a net 69,000 jobs, with an increase of 82,000 private jobs and a fall of 13,000 government jobs. Based on the growth rate of the labor force over the ten year period of 2002 to 2012 (there is a good deal of fluctuation in monthly figures), the labor force is growing at about 83,000 workers per month on average. Employment growth in May of just 69,000 jobs does not keep up with this, much less make a dent in the still high unemployment.

The figures released this morning were also disappointing in the revised numbers they showed for April. Last month, the initial estimates were that April total employment had risen by 115,000 jobs, with private jobs growing by 130,000. These were already not good, but the revised estimates issued this morning based on more complete data indicate total jobs in April grew by only 77,000 jobs, with private jobs growing by just 87,000 jobs. With the May numbers of 69,000 and 82,000 for total and private jobs, respectively, we now have two months of disappointing job growth. Unless the May numbers are significantly revised when more complete data becomes available, we cannot say that this is only a one month fluke.

As one can note from these numbers, private job growth has been consistently above total job growth. That is because government continues to cut back on the number of workers it employs, despite assertions by Mitt Romney and other Republicans that government has been growing. The graph above shows the monthly changes in employment of both private and government employees over the last year and a half, where one sees that government employment has been falling in all but two of these months. Note that the government figures in the graph are for total government, including at the state and local level. But the underlying figures show that the fall has been in employment both at the federal and at the state and local levels.

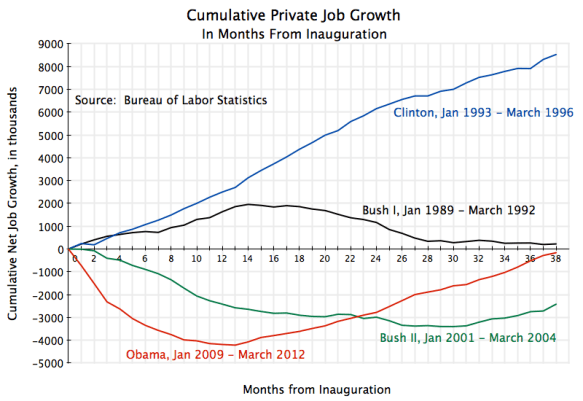

This steady fall in government employment depresses overall job growth, and adds up over time. Between January 2009, when Obama was inaugurated, and May 2012, total government jobs fell by 607,000. In contrast, over January 2005 and May 2008, the comparable period in Bush’s second term, total government employment rose by 743,000. If government employment had been allowed to grow as much during the Obama period as it had during the Bush period, the difference would have been an additional 1.35 million jobs. This difference alone would have brought the unemployment rate down from the current 8.2%, to just 7.3%. But one would expect with the still depressed economy, with unemployment high, that increased government employment would have spurred some private job growth. Assuming conservatively a multiplier of two (i.e. there would be one additional private job for each additional government job, to produce what the now employed government workers will spend on), the unemployment rate would have dropped to just 6.5%.

That is, had government employment been allowed to grow during the Obama period by as much as it had during the comparable Bush period, unemployment would have dropped to 6.5%. With full employment generally considered to be in the range of 5 to 6% currently, this would have brought employment most of the way to full employment.

The other disappointing report was on estimated GDP growth in the first quarter of 2012, released by the Bureau of Economic Analysis on May 31. This was the regular first revision of the initial estimate of GDP growth that had been released a month ago. The initial estimate of GDP growth in the first quarter of 2012 was discussed in a posting on this blog in April. The initial estimate was that GDP had grown at a 2.2% annualized rate in the first quarter. This estimate has now been revised downward to 1.9%.

The revision is not large, but is not in a good direction. And it is interesting to note that two-thirds of that downward change (0.2% points of the 0.3% points reduction) was due to a downward revised figure on government spending. Government spending was already falling, and the initial estimate, discussed in the blog post cited above, was that it took 0.6% points away from what GDP growth would have been. The revised estimate increases that reduction to 0.8% points of GDP. Government spending on goods and services (for all government, including state and local) is estimated to have declined at an annualized rate of 3.9% in the first quarter, similar to the 4.2% rate fall in the fourth quarter of 2011.

The reduction in government demand for goods and services leads to a reduction in GDP in present circumstances since unemployment is high, there is substantial excess capacity, and hence goods and services produced for sale to government will not come from goods and services that could be sold elsewhere. There is plenty of capacity to produce whatever people demand, and the problem is there is no demand for additional goods and services to be sold elsewhere.

This fall in government spending, especially in the last half year (i.e. the fourth quarter of 2011 and the first quarter of 2012), can explain a large part of the recent slow growth. As noted above, the revised GDP estimates indicate that the fall in government spending in the first quarter of 2012 subtracted 0.8% points from what GDP growth would have been. There was a similar 0.8% point reduction in the fourth quarter of 2011.

But far from simply not falling, government spending will grow in a normally growing economy. Hence the basis of comparison should not be to zero government spending growth, but rather something positive. One comparison to use would be the growth seen during the Bush administration. Over 2001 to 2008, government spending growth on average accounted for 0.42% points of GDP growth at an annualized rate. Keep in mind that this spending growth is for all government, not simply federal spending (which was high), but also state and local government spending. Also, government spending in the GDP accounts is for direct goods and services only, and excludes spending via transfers (such as Social Security).

Finally, government spending growth in periods such as now, when unemployment is high and there is excess capacity, will have a multiplier impact, for the reasons discussed above. A reasonable and conservative multiplier to use would be a multiplier of two.

The table below summarizes the impact of these assumptions for what growth would have been in 2011Q4 and 2012Q1:

| Annualized growth rate of GDP | 2011Q4 | 2012Q1 |

| GDP Growth Observed | 3.0 | 1.9 |

| GDP Growth if Government had not contracted | 3.8 | 2.6 |

| GDP Growth if Government had grown at the Bush rate | 4.2 | 3.1 |

| GDP Growth if Government had grown at the Bush rate, with a multiplier of two | 5.5 | 4.3 |

GDP growth as actually happened was at a 3.0% rate in the fourth quarter of 2011 and 1.9% in the first quarter of 2012. Had reductions in government spending not taken away 0.8% points from these growth rates in each of these two periods, growth would have been 3.8% and 2.6% respectively. But this implicitly places government spending growth at zero. Had government been allowed to grow as it had between 2001 and 2008 during the Bush terms, growth would have been 4.2% and 3.1% even with no multiplier. With a multiplier of two, the rates would have been 5.5% and 4.3% respectively.

Such growth rates of about 5% on average is what the economy needs if it is to recover. At 2% or so, growth is insufficient to create sufficient demand for labor to bring down unemployment on a sustainable basis, as we have just seen in the report this morning. And a 2% growth rate is so modest that it is vulnerable to shocks, such as from Europe (where Germany and the EU still have not addressed what needs to be done to resolve the Euro crisis), or from a spike in oil prices (should the Iran situation blow up, literally), or even from swings in inventories (as discussed before in this blog).

With government contracting as it has, despite the high unemployment and excess capacity, fiscal drag is acting as a severe constraint on economic growth. There is a not a small danger that growth could slip back to negative rates, and that is not good for an incumbent President in an election year.

You must be logged in to post a comment.