A. Introduction

What to do about health care has been a central issue debated by the candidates seeking the Democratic nomination for the presidency. Different proposals have been made, but two underlying factors drive the issue. One is that health care costs in the US are high – far more than what they were not so long ago, and far higher than what health care costs in other countries. The second and related issue is that despite such a high amount being spent, and despite as well a marked improvement under the Obamacare reforms, the US still has a substantial share of its population who are uninsured and hence suffer from a lack of effective access to the health care system.

This post will look at those issues at a macro level, basically through a series of charts. I have been working on a post that examines the Medicare-for-All proposals, where the plans now issued by Elizabeth Warren are the most specific and detailed. But it is useful first to set the context by reviewing the high costs for the US (while yielding only mediocre health outcomes), as medical care and how to pay for it would not be the prominent, and difficult, issues that they now are if we were not spending so much.

B. Health Care Expenditures as a Share of GDP

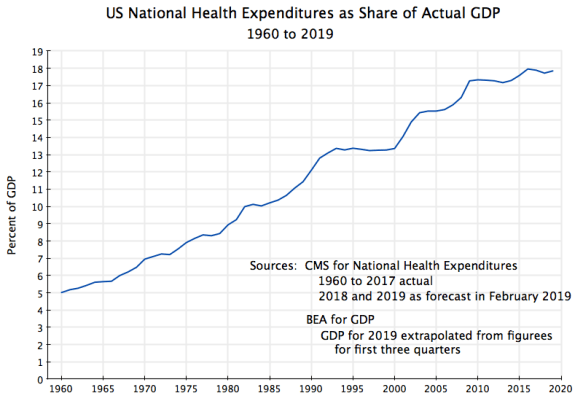

A commonly used measure, which allows comparisons both over time and between countries, is the amount being spent on health care as a share of GDP. The chart at the top of this post shows this for the US, with national health expenditures (whether from private sources or from public, and for investment as well as for current consumption of the services) going back to 1960.

The figures on national health expenditures are as published by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), which provides each year authoritative and detailed figures on such expenditures, both historical and projected. The most recent historical figures cover the years through 2017, while the accompanying forecasts (for 2018 to 2027) were issued in February 2019. The figures used in the chart above for 1960 to 2017 come from the historical tables, while the 2018 and 2019 figures come from the first two years of the 2018 to 2017 forecasts. The GDP figures come from the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA), where the 2019 figure is based on a simple extrapolation of the current estimates for the first three quarters of the year.

It was not so long ago that the US spent far less on health care than it does now. In 1960 it was only 5.0% of GDP. But this then rose, fairly steadily, to 8.9% in 1980, 13.4% in 2000, and close to 18% of GDP now. Note that by examining this as a share of GDP one is taking into account that as a country grows richer, it can spend more on health care (as well as on everything else) with a share that is unchanged. But in the US the share itself has increased dramatically.

Note also that as a share of GDP one is taking a ratio of a nominal magnitude (what is being spent on health care, in current dollars) to a nominal magnitude (overall GDP, also in current dollars). There is therefore no issue of whether the price indices for health care services are being measured correctly (and in particular whether they are reflecting quality changes correctly), as price indices do not enter. Rather, one is simply adding up all that is being spent on health care services, and comparing this to a broad concept of national income and output.

But while this chart is an accurate portrayal of how much is being spent on health care as a share of actual GDP in any period, fluctuations in the curve could be due either to changes in health care spending from one year to the next, or due to changes in GDP from one year to the next. One can see that there were particularly sharp upward movements in the share in those years when the economy went into recession (such as in the early years of the Reagan presidency, again when Bush Sr. was president, again in the early years of the Bush Jr. presidency, and then especially sharply in his last year in office). The curve flattened out in the years of strong economic growth (such as during most of the Clinton presidency).

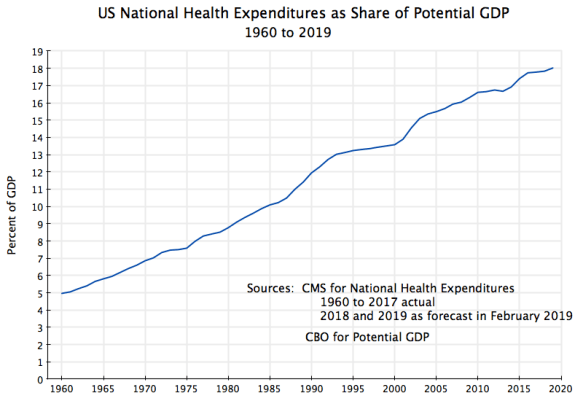

One can control for these business cycle fluctuations in GDP by calculating the health care expenditures as a share of potential GDP rather than as a share of actual GDP:

Potential GDP is an estimate of what GDP would have been in any given year, had employment been at full employment levels. The estimates of potential GDP used here come from the Congressional Budget Office, which comes up with careful estimates of potential GDP as part of its budget work.

Potential GDP grows at a steady pace, unlike the business cycle fluctuations of actual GDP. And with this, one does not see the degree of fluctuations in the curve for health care spending as one has with actual GDP. What this implies is that health care spending grows at a relatively steady rate, whether the economy is growing well or has gone into a downturn. The rise in the share during economic downturns, when measured in terms of actual GDP, thus is primarily due to the reduction in those years of the denominator (GDP), rather than a sudden rise in the numerator (health care spending).

This should not be surprising, except to those who think consumers treat health care spending as a discretionary expense which they can control. That is, conservative analysts (and Republican congressmen) have advocated for health funding systems where the patients face a high share of their health care costs (and a 100% share in high deductible health insurance plans, except in catastrophes). The presumption is that patients have a good deal of choice in whether to seek health treatments or not. If this were the case, one would find health care spending falling along with GDP when the economy goes into a downturn, due to higher unemployment in such times (with the unemployed losing their previous health insurance cover) and money in general being tight. But one does not see this. Rather, health care is a necessity, which one needs regardless of the state of the economy.

There are still some modest fluctuations in the curve, coinciding with periods where administrations have focused on health care costs. Thus one sees a flattening of the curve (relative to the overall trend) during the Clinton years (1993 to 2000), and again after the Obamacare reforms were passed in 2010. But overall, the curve has steadily risen, from 5% of GDP in 1960 to 18% now. This increase, by a factor of 3.6, is extraordinary.

C. US Health Care Spending and Outcomes Compared to Other Countries

Not only has US health care spending increased by an extraordinary amount over the last several decades, but it is also far higher than what other countries spend:

This chart, as well as those immediately below with other cross-country comparisons, are updated versions of several from an earlier post on this blog. That earlier post also has additional comparisons and detail which readers may find of interest, but have not been replicated here due to space. But they still apply.

The earlier charts were for 2011, while these are now for 2017. Both sets are based on health care data assembled by the OECD for its member countries. Standard definitions are set by the OECD to allow cross-country comparisons.

As the chart above shows, the US still stands out, as before, by spending far more for health care (as a share of GDP) than any other country. Note that the figures here only include expenditures on current health care services. The OECD had earlier included also health care expenditures for investments (such as for hospital buildings, for research, and so on), but now places investment expenditures in a separate, and only partial, table. While the investment figures are readily available for the US, it appears they are difficult to obtain for a number of others. Hence the OECD now treats it separately, in a table with a large number of blanks.

But the US spending on current health care services, at 17.1% of GDP, is still far ahead of such spending by the second-ranking country – Switzerland here. And the US spends close to double the OECD average.

Such exceptionally high spending does not, however, yield exceptionally good health outcomes. Indeed, by a number of standard measures US health outcomes are among the worst in the OECD, where the only countries that are worse are those with a far lower income than what the US enjoys.

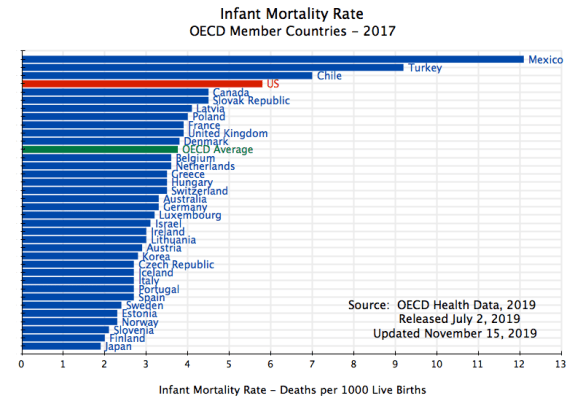

First, one can look at infant mortality rates:

Only Mexico, Turkey, and Chile have a higher infant mortality rate than the US does. And there is a huge room for improvement. The infant mortality rate in Japan is only one-third that of the US. Yet Japan spends less than 11% of GDP on health care services, compared to the more than 17% of GDP in the US.

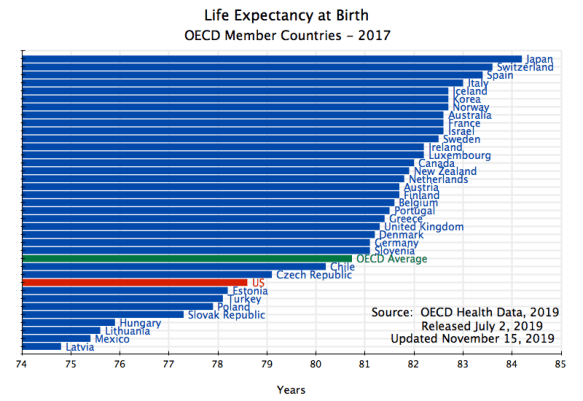

Life expectancy is also a standard measure of health care outcomes:

Only a number of countries from Central Europe. as well as Turkey and Mexico, have a lower life expectancy than that of the US. And they all have far lower incomes than the US.

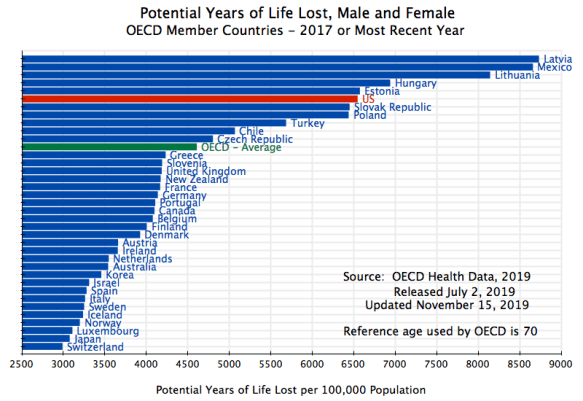

Finally, a measure more commonly used by health care professionals takes into account how death rates vary by age. That is, given the age profile at which deaths occur in a country, the “potential years of life lost” measure multiplies the number of deaths that occur at any given age by the difference between that age and a reference age (where the OECD uses age 70 for this benchmark). It then takes the sum across all ages, and computes this per 100,000 of population. Thus a death at age 50 will receive twice the weight of a death at age 60, as a person dying of some disease at age 50 would have had 20 more years to live to age 70, while a person dying at age 60 would have had only 10 more years to live to age 70.

The US once again comes out poorly, even by this more sophisticated measure:

Only several countries of Central Europe, plus Mexico, are worse than the US. Even Turkey is better. All the countries of Western Europe, as well as Japan, Korea, Australia, and Canada, are far better.

D. The Impact of the Uninsured

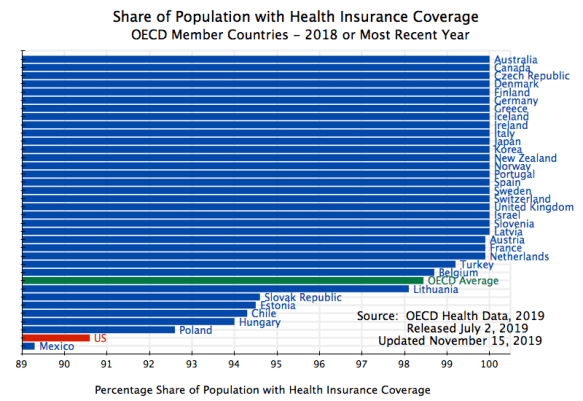

At least part of the reason for these poor health outcomes in the US compared to the high-income countries of Europe and Asia is that the US, despite spending more, has a high share of its population left uninsured. All those other high-income countries have universal health insurance cover (with the partial exception of Belgium, where coverage is 98.7%):

US health insurance coverage (under the standardized definition of the OECD) is only at 90.6%. Only Mexico, among OECD members, is worse.

Taking this into account, the US spending figures are even worse than they at first appear. Not only does the US spend on health care services a far higher share of GDP than other OECD member countries do, but that higher spending is concentrated on less than the full population due to the high share of uninsured. The uninsured do, of course, have certain health care costs, which they pay for, to the extent they can, out of pocket, by charity, or for certain services under various government programs (such as for public health) that cover everyone. But overall, the uninsured are more limited in what they can obtain in health care services than what an insured person can.

With the Obamacare reforms, the share of the population in the US without health insurance fell significantly, for the first time in a generation. While the Trump administration has done all it legally can to reverse these gains, the impact so far (up to 2018, where note the figures here are annual averages) has been only partial:

The figures come from the American Community Survey (ACS) of the US Census Bureau, by way of a Kaiser Family Foundation analysis of the ACS results (and with 2018 based on figures in the 2018 Census Bureau report on Health Insurance Coverage).

The figures come from the American Community Survey (ACS) of the US Census Bureau, by way of a Kaiser Family Foundation analysis of the ACS results (and with 2018 based on figures in the 2018 Census Bureau report on Health Insurance Coverage).

With Obamacare (more formally, the Affordable Care Act), the share of the US population without any health insurance fell from 15% in 2010 to 9% in 2015 and 8.3% in 2016. The Affordable Care Act was passed in 2010, and while certain of the reforms went soon into effect (such as the requirement, effective in 2011, that sons and daughters up to age 26 could remain on their family health insurance plans), the primary changes entered into effect in 2014, with the opening of the Obamacare market exchanges and the Medicaid expansion.

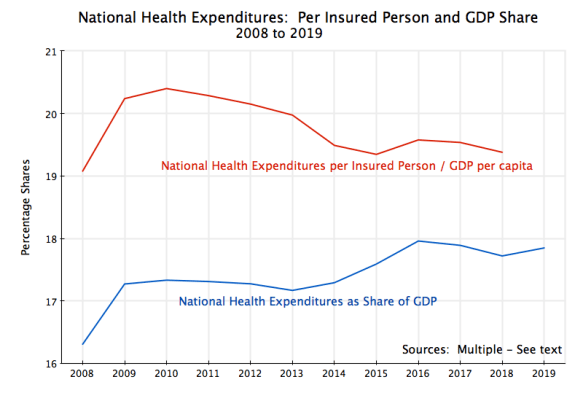

With this significant reduction in the number uninsured, an interesting question is whether this might account for some or all of the increase in observed national health expenditures as a share of GDP in the years of that expansion in coverage. This chart will help address this:

The lower curve in the chart, in blue, shows national health expenditures as a share of GDP, and is the same, and from the same sources, as in the chart at the top of this post. The only difference is that the focus now is only on the period since 2008. The curve was basically flat (indeed falling a bit) from 2009 to 2013. It then rose from 2014 to 2016, which is the period that coincides with the substantial reduction in the share of the population that did not have health insurance.

An analogous curve for just the insured is then shown as the top curve in the chart, in red, and plots what national health expenditures were per insured person in the US, with this then taken as a share of GDP per capita. Note that national health expenditures as a share of GDP (the blue curve) is the same as national health expenditures per person, with this then taken as a share of GDP per capita (i.e. with both numerator and denominator divided by the population). The sources are the previously cited Kaiser Family Foundation report and ACS for the number uninsured, the Census Bureau for population, and the BEA for GDP.

If 100% of the population were insured, the two curves would coincide. As the share who were uninsured fell following the Obamacare reforms, the two curves approached each other. And it is interesting that the costs per insured person fell after 2010, with an especially sharp fall in 2014 and a smaller reduction in 2015.

But as was noted previously, to see the underlying trends one should remove the impact of the cyclical fluctuations of GDP, by calculating the shares in terms of potential GDP. When one does this one finds:

National health care costs per insured person (as a share of potential GDP per capita) fell in 2014, the year the number of uninsured fell sharply, and in 2015 was still below earlier levels. But it has risen fairly steadily from 2015 onwards. The increase in national health care costs (as a share of GDP) in 2014 and 2015 therefore can be attributed to the expanded coverage achieved in those years. But after 2015, the steady and similar increases in both curves suggest a return to the earlier trends of rising health care costs.

E. Conclusion

The US spends an extraordinary amount on health care. No other country comes close. Furthermore, what the US spends, as a share of its GDP, has risen dramatically over recent decades, from just 5% of GDP in 1960 to almost 18% of GDP now. And while other developed countries have been able to attain universal health insurance coverage despite spending far less, the US has not. The Obamacare reforms helped, but the Trump administration is trying to do all it legally can to reverse those achievements.

It is these high costs that are basically driving the need for fundamental reform in the US health care funding system. The current path is not sustainable. But whether reforms will be enacted to reverse those cost trends, or at least flatten them out, remains to be seen.

You must be logged in to post a comment.