A. Introduction

News reports are saying that the Senate Republican tax plan, rushed through and passed on a 51 to 49 vote late on a Friday night (actually, at 2 am on Saturday), will add an estimated $1.0 trillion to the national debt over the next ten years. The number is based on figures provided in a staff report from the Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) of Congress on the estimated tax revenue impacts. But that is not what the JCT numbers say. The actual increase in the federal debt will be almost a quarter more than that $1.0 trillion figure, even taking the JCT estimates as fine. The problem is that they are being misinterpreted.

The JCT acts as a professional staff responsible for assessing the impacts of tax proposals before Congress (on behalf of both the Senate and the House), and must act in accord with instructions provided by the Congressional leadership. They have traditionally worked out the revenue implications of the proposals sent to them (normally on a year by year basis over a ten-year horizon) as well as the distributional implications (what will be the effects by income group). When Republicans took control of both the Senate and the House following the 2012 elections, JCT staff were also directed to provide what has been labeled “dynamic scoring”, which attempts to come up with an estimate of how economic growth may be affected and the revenue implications of that. The assumption is that tax cuts will spur growth, and that with higher growth there will be an increase in tax revenues which would then (partially or possibly fully) offset what the revenue losses would otherwise be as a result of the tax cuts.

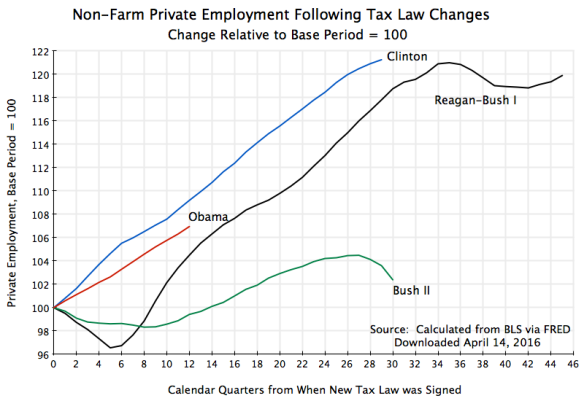

This is the old “supply-side economics”, which politicians starting with Reagan would cite as saying that tax cuts can pay for themselves. The reality has been far different, as previous posts on this blog have argued. The tax cuts of Reagan and Bush were followed by higher deficits, and slower (or at least not faster) growth than what followed after the tax increases approved under Clinton and Obama. A fair reading of these experiences would not be that tax increases are good for growth and tax cuts bad for growth, but rather that the impacts, whatever they are, are too small to see in the data.

But the JCT staff are now required to provide some such estimate, and to do this they have to use economic models. The constraints of such an approach will be discussed below. But there is also a separate issue, which has unfortunately been confused with the impact of the growth estimates. The issue is that the figures being provided by the JCT, on the year by year impact on tax revenues of the tax plan, are being confused with how far government debt will rise as a result of those tax losses. Reporters are adding up the year by year tax revenue impacts over the ten year period of the forecasts, and concluding that that total will equal the resulting increase in government debt. But that is not correct. That simple addition of the year by year figures on tax losses leaves out the additional interest that will need to be paid on the debt incurred to cover those now higher fiscal deficits. That additional interest will be significant.

B. The Impact of Increased Interest on the Addition to the Federal Debt

The black curve in the chart at the top of this post, rising to $1,414 billion by FY2027, shows the simple accumulation of the lost tax revenues (year by year) following from the Senate Republican tax plan (November 16 version, as assessed by the JCT on November 17). While the final plan passed by the Senate was a bit different (loopholes were being added or expanded up to the final hours, with also some offsetting tax increases), the net change in revenues in the final, approved, bill was relatively small, at $34 billion over the ten years (raising the cost to $1,448 billion from the $1,414 billion cost the JCT had estimated for the earlier version). The JCT estimates of the macro impacts based on the $1,414 billion total will be close to what it would have been had they had the time to assess the final plan.

That path leading to the $1,414 billion cost total reflects the simple sum of the year by year tax revenue losses as a result of the Republican tax plan. But those revenue losses will lead to larger deficits. The larger deficits will mean additional federal debt, and interest will have to be paid on that additional debt.

Such additional interest needs to be paid year by year, and will accumulate over time. The blue curve at the top, rising to $1,717 billion, is an estimate of what this would be, using the June 2017 interest rate forecasts (on government debt) from the Congressional Budget Office, and assuming, conservatively, interest paid in arrears with a one-year lag. The total is $300 billion higher than the $1,414 billion figure. That is, under this scenario federal government debt would increase by $1,717 billion over what it would otherwise have been by FY2027, not by the $1,414 billion figure. News reports commonly got this wrong. It is not that the JCT got it wrong. Rather, news reports misinterpreted what the JCT figures were saying.

The question then is whether there will be macro economy impacts, as the supply-siders assert, and if so, how large they would be. The JCT provided on November 30, estimates of what these might be. Based on a weighted average of results from three different economic models of the economy, the JCT estimated that at the end of the ten year period (i.e. in 2027), GDP would be 0.8% higher than it would be otherwise. That is, the growth rate would on average be 0.08% per year higher than otherwise. This is not much but still is something. The resulting higher GDP would raise tax revenues above what they would otherwise be following the tax cuts. Tax revenues would still decline – they just would not decline by as much as before. Federal debt would still rise. The higher deficits over the ten years would sum to $1,007 billion by 2027 (the green curve in the chart above). And once again, news reports concluded that the new JCT figures were saying that federal debt would rise by $1.0 trillion over the ten year period once those macro impacts were taken into account.

But the JCT figures are not saying that. They simply show the year by year impacts. And as before, the JCT figures do not include the impact of the increase in interest that will need to be paid on a federal debt that would be higher than otherwise due to the tax cuts. Adding in these interest payments, on a growing debt resulting from the yearly reduction in tax revenues in this tax plan, leads to the red curve in the chart. The JCT figures imply, once one adds in the now higher interest payments due, a federal debt that by 2027 would be $1,245 billion higher than what it would otherwise be. This is roughly a quarter higher, or an extra $240 billion, over the figure the news reports are citing. This is not a small difference.

C. Other Points

There are a few other points worth noting:

a) One can see in the chart at the top of this post how the additions to the federal debt level off in 2026, and in most cases then decline. This is because most of the provisions that would cut individual income taxes are ended as of the end of CY2025 under the Republican proposal. The losses in tax revenues from the tax plan would then continue to grow through FY2026 (due to the overlap between CY2025 and FY2026, and the fact that final taxes due for CY2025 will be paid in April 2026) leading to still growing debt in 2026, but then level off or fall after that. By FY2027, the JCT assessment found that most individuals would end up with higher taxes due. Indeed, the Senate Republican tax plan is structured so that individuals in FY2027 would on average end up paying more in taxes than they would if this tax plan were never to go into effect. In contrast to the sunsetting of the individual income tax cuts, the corporate income tax cuts would be made permanent. And if, as the Republicans say they actually want, the individual income tax cuts are also made permanent, then the federal debt will grow by even more than what would result under the current plan. They cannot have it both ways.

b) Furthermore, while the focus here is on the impacts on total revenues collected and hence on the federal debt, there will also be critical distributional implications. The JCT assessment of the November 16 version of the Republican tax plan found that if one adds together the impacts on households of all the proposals (on both the individual and the business side), that in 2027, those families with incomes of less than $75,000 would be paying more in taxes than they would if this tax plan were never approved (taking averages for each income group, as individual experiences will vary). However, those with incomes of $75,000 or more would all be enjoying tax cuts. The figures on a per family basis (technically per taxpayer unit) are shown in my earlier blog post on the Republican plan. But it is not just in 2027 that certain income groups will be paying more in taxes. Adding up the net impacts by income group over the full ten years, one finds that those with incomes of up to $30,000 will be paying more in taxes in total over the full ten years (of about $900 per family on average). These are the families who are least able to afford a tax hike.

c) It is important to clarify one statement in the JCT report on the macro impacts. It makes reference to a $50 billion figure for “an increase in interest payments on the Federal debt”. This is stated in the opening paragraph, and then in a bit more detail on page 6 in the section labeled “Budgetary effects”. This increase in interest due is netted out in the figure summing to the $1,007 billion for the total cost over ten years of the Republican plan.

At first I had thought this interest cost reflected what I am discussing here – the increase in interest payments that will be due over the period as a result of the greater borrowing following from the higher deficits. However, the $50 billion number is far too small, as the higher amount due in interest from the higher debt would be more like $240 billion. I at first thought there might have been a mistake in the JCT calculations. But a close reading of the JCT report shows that the $50 billion figure is actually referring to something else. That something else is that one should expect general interest rates to rise in the economy as a result of the higher fiscal deficits, and that this will then lead to higher interest due on the existing federal government debt. The increase in interest rates might be relatively small, but with the large government debt, even a small increase in interest rates can matter. And one can calculate that a $50 billion increase in interest due would result from a rise in average interest rates on government debt of 0.025%, i.e. from the 3.7% that the CBO forecasts for most of this period, to 3.725%.

One must therefore not confuse the $50 billion in increased interest payments due on the existing federal debt (which the JCT estimates), with the increase in interest that will be due as a result of the year by year higher federal deficits, which must then be funded by borrowing. The JCT, following the instructions given to it by the Congressional leadership, is not estimating the latter. But the latter does add to the federal debt, and hence the addition to the federal debt by 2027 as a consequence of this Republican tax plan would be more like $1,245 billion than the $1,007 billion that the news media is mistakenly saying.

d) As noted above, the JCT arrives at a forecast, based on the models it is using, that GDP would be 0.8% higher in 2027 than it would otherwise be. The increase is small (increased growth of just 0.08% a year), but something. News reports have made much of it. But not noted (from what I have seen) is any discussion in the news reports of what the JCT estimated would happen after that.

The JCT discusses this on page 6 of its report. It notes that due to the reversal of most of the individual income tax cuts (while leaving in place measures that would lead to higher individual income taxes), coupled with the rising interest rates resulting from the higher deficits (the $50 billion figure discussed above, but growing over time), the impact on GDP by the end of the third decade of such measures would be partially or wholly offset. The growth effects die out over time. As a result, we will then be left with a higher federal debt, but GDP the same or similar, and hence a government debt burden that is then higher for our grandchildren than would be the case if this tax plan were never approved.

e) And it is critically important to recognize that the JCT could only arrive at its estimates of what the impact would be on GDP via economic models. They did recognize that any individual economic model has issues, and therefore they used three different ones. The 0.8% increase in GDP forecast for 2027 was the weighted average outcome of those three, weighting them not equally, but rather by 40/40/20. Each model approaches the issue differently. And while the JCT report is honest on what they did, and did report on the numbers used for some of the key parameters in each of the models, one would have liked to see more.

To start, only the 0.8% figure was given, resulting from the weighted average of the individual model forecasts. One would have liked to have seen what the individual model results were. Were they all fairly close to the 0.8% figure (in which case one would take some comfort in the similar findings), or did the different models produce quite different forecasts? If the latter, one can not place much confidence in the overall weighted average as providing a robust estimate.

But more fundamentally, one needs to recognize that these are forecasts produced by models. The results the models will produce will depend on the model structure assumed (as set by the analyst), and on the specific values assumed for the key model parameters. The fact that the JCT used three different models for this (and reasonably so) shows how unsettled such analysis is. Different models can come up with completely different results, as different aspects of the economy will be emphasized by each modeler.

The fundamental problem is that it is difficult to impossible to be able to say from actual data observed what the best model might be. The overall net effects on growth are just too small, and there is so much going on also with the economy that one cannot come up with robust estimates of the impacts of such changes in tax law. It is important to recognize that changes in tax law can have expansionary effects in some areas (including not just in different sectors but also in different areas of economic behavior) and contractionary effects in others. The overall impact will depend on the net impact of them all, and this can be small to non-existent as the individual effects can go in opposite directions. Hence one does not see in the observed data on GDP any indication that such changes in tax law (as have occurred in the past) have led to higher (or lower) GDP.

This was discussed in a previous post on this blog with regard to the impact on labor supply (and hence output) from a change in individual income tax rates. There are income effects as well as substitution effects, their impacts go in opposite directions, and the net impact may then be small or not there at all as they simply offset each other. There is a similar problem with assessing the impact on investment from changes in the corporate income tax proposals. While some would argue that a lower corporate income tax rate will spur investment, the proposal also to limit the deductibility of interest on borrowed funds will act to reduce the incentive to invest. The weighted average cost of capital (after taxes) will be higher when interest is not deductible, and the decision to invest depends on the balance between the (after-tax) expected return on investment and the (after tax) weighted average cost of capital for the funds being invested.

The net impact on the economy is therefore an empirical question, and one cannot say from ex-ante theorizing alone what that net impact might be. One can construct models based on different theories, but then the net impact will depend on the model structures assumed and the specific values chosen for the various parameters used. These can be difficult to impossible to estimate independently.

Finally, any such models will only be able to focus on a few of the possible changes in tax law. They will not have the granularity to assess properly the literally hundreds of changes in law that the Republican tax plan includes. Depending on the success or not of different interest groups and their lobbyists, the Republican tax plan has special favors, or harms, for different groups, and no economic model can capture all of them. The models used by the JCT are, of necessity, much broader.

D. Conclusion

To conclude, the JCT report on the macro impacts from the Republican tax plan is important and valuable, but is typically being misinterpreted. The increase in the federal debt resulting from the tax cuts will be significantly higher than what one obtains by a simple summation of the year by year revenue impacts, as those impacts do not take into account the interest that will need to be paid on the now higher federal debt. Those additional interest payments will be significant, and the addition to the federal debt will be about a quarter higher by the end of ten years than what a simple sum of the year by year losses in tax revenue would come to.

The JCT also concluded that its best estimate of the impact on GDP of the tax plan after ten years was that GDP would be 0.8% higher. This is not much – an increase in the growth rate of just 0.08% a year. Furthermore, even this would die out by the end of the third decade, in the tax plan as proposed. The nation would then end up with a higher debt, a GDP which is about the same, and hence a debt to GDP ratio which is higher.

But of necessity, the estimates of the impact on GDP from the tax plan are crude. The JCT was required to come up with such an estimate, but the only way to do this is to assume some economic model applies. There is no good basis for choosing one, so the JCT used three, and the 0.8% figure is a weighted average of what those three different models forecast. It would have been nice to see what each of those three forecasts were, to see if they were broadly similar.

All one can reasonably conclude is that the net impact on GDP is likely to be small. This is consistent with what we have seen historically. Any impacts on GDP, positive or negative, from such tax law changes have been too small to see in the data. And there is certainly no reason to believe that such changes in tax law will lead to such a strong response in growth that the tax cuts “will pay for themselves”. This has never happened before, and the JCT results indicate it will not happen now.

You must be logged in to post a comment.