A. Introduction

The Affordable Care Act (ACA, and also often referred to as ObamaCare) has been working well by any objective measure. There are now more than 10 million additional Americans who have health insurance who could not get affordable health care before; the share of the uninsured in the US population is now a quarter less than what it was before the individual mandate of the Affordable Care Act went into effect; and this has been achieved at premium rates for the new plans that are reasonable and well less than opponents charged they would be. Health care costs have also stabilized under Obama, both as a share of GDP and in terms of health prices relative to overall prices, in contrast to the relentless increases in both before. And while some have criticized this, it is good that there are now minimum quality and coverage standards in health insurance plans. Such standards are good in themselves. And without such standards, purported health care “plans” which offer next to nothing (due, for example, to extremely high deductibles) and which can then cost next to nothing, would lead to a death spiral for genuine health care plans that cover costs when you are sick and need treatment.

Gains from the ACA are also reflected in the findings of a recently published report from The Commonwealth Fund. The Commonwealth Fund has been organizing a periodic survey on health care coverage since 2001. The most recent survey (for 2014) found that for the first time since the question was first asked in 2003, there was a reduction in the number of Americans avoiding (because of cost) health care services that they needed. And for the first time since the question was first asked in 2005, the number reporting medical bill or debt problems also fell. Personal financial distress due to medical problems has been reduced, due to greater access to health insurance and due to health insurance plans that now meet minimum standards.

Despite this (but not surprisingly given the position they staked out against the reform), the Republican Congress continues to vote to repeal, or at least weaken, the law. The most recent vote was aimed at the provision in the Act which complements the individual mandate to purchase health insurance, with an employer mandate requiring firms with 100 full time equivalent employees or more from January 1 of this year (and with 50 or more from January 1, 2016) to offer health insurance to their full time employees or pay a fee. The proposed Republican bill would change the definition of a full time worker from one who normally works 30 hours or more a week, to one who works 40 hours or more a week.

The supporters of the change charge that the prospect that employers (with 50 or 100 employees or more) will soon be required to offer health insurance to their full time employees has led firms to cut working hours of their employees, to shift them from full time to part time status, and hence avoid the employer mandate of the ACA. As a Republican congressman from Texas said: “We have heard story after story from every state in the union that employers are dropping workers’ hours from less than 39 hours a week to perhaps less than 29.”

This accusation is confused on several levels. This post will first look at whether there is in fact any evidence that workers are being shifted from full time to part time status as a result of the ACA (or indeed for any other reason). The answer is no, at least at the level of the overall economy. Second, there has been a good deal of confusion in the discussion on what the issue really is with regard to part time workers, including by prominent congressmen such as Paul Ryan. Either Ryan does not understand what the employer mandate is, or if he does, then he has deliberately mischaracterized it.

The public discussion has also avoided altogether the real issue. It is not that firms with 50 workers or more would be required to offer health insurance to their employees (most do already), but that this insurance is only made available to their full time workers. Part time workers get nothing, no matter what size firm they work at. The final section of this blog post will discuss a way to resolve this equitably.

B. What is the Evidence on Whether the ACA Has Increased the Ranks of Part Time Workers?

The opponents of ObamaCare assert that as a result of the employer mandate, firms have been shifting workers from full time to part time status. E.g., instead of employing one worker for 40 hours, they are choosing to employ two workers for 20 hours each. If true, the ratio of part time workers to the total employed will rise.

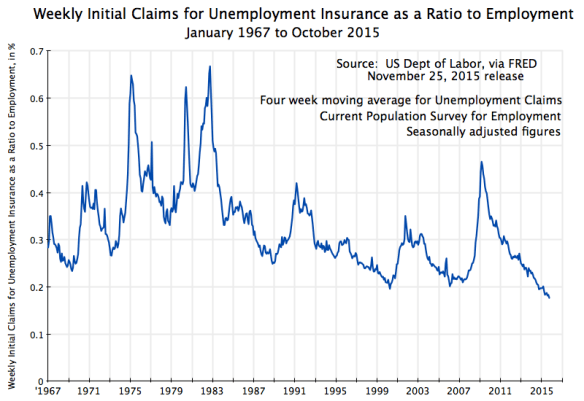

The chart at the top of this post shows this has not been the case. It is based on data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, from its Current Population Survey. This monthly survey of households is used to determine the unemployment rate among other statistics. The households surveyed are asked whether household members are employed full time or part time (if employed), and if part time, whether this is by choice (because they only want to work part time) or because they want a full time job but cannot find one. The chart above shows the ratio of workers who are working part time not by choice but for economic reasons, to all workers employed. Note that the BLS data defines a part time worker as one with fewer than 35 hours of work per week. While this differs from the 30 hour standard in the ACA, as well as the 40 hour standard in the recently passed Republican legislation, the results in terms of the trends should be similar. The BLS does not publish data with a different cutoff in terms of hours per week for what is considered part time work.

As in any economic downturn, the ratio rose rapidly in the economic collapse of the last year of the Bush administration. Regular jobs were disappearing, with some of them shifting to part time status. Indeed, the absolute number of part time jobs was increasing at the time, even as the total number of jobs was falling, thus leading to two reasons for the ratio to rise, and rise rapidly.

The ratio reached a peak soon after Obama took office, and began to fall about a year later. Since then it has fallen at a fairly steady pace in terms of the trend. There were sometimes relatively sharp month to month fluctuations in the data, but this can be on account of statistical noise. The data comes from a limited sample of households, with only 5 to 6% or so of those employed on part time status (for economic reasons) for most of this period, so the statistical noise in a relative sense (month to month) will be large. But the downward trend over time is clear, and at a similar downward pace for close to five years now.

What one does not see is any shift in this downward trend linked either to the signing of the Affordable Care Act in March 2010, or to the start of the individual health insurance mandate in January 2014, or to the anticipation of the start of the employer health insurance mandate in January 2015. Note that since the classification of a worker as a full time or part time worker (and hence the classification of the firm as crossing the 100 or 50 full time worker standard) will be in a period of up to 12 months before the employer mandate goes into effect, one would have seen an impact in 2014 if the 2015 mandate mattered. There is no indication of this.

The data cover the overall economy. The figures refer to millions of workers as well as millions of employers. The US is a large place. Within such a large place, it will undoubtedly be possible to find particular cases where employers will say that they reduced worker hours to part time status so that they could avoid the health insurance employer mandate. And one could indeed probably find a long list of firms making such statements. It would be even easier to find a long list of firms and other entities where working hours were cut, whether or not there was any employer mandate pending. In a dynamic economy, there will always be a large number of such cases (along with a large number of cases of firms going in the opposite direction, converting part time jobs to full time jobs).

Such anecdotal information, and even a long list of such anecdotes, is not evidence of an issue of substantial scale. As seen above, there is no evidence of it in the overall numbers. But one should still recognize that the issue could exist in particular cases. The question, however, is what is the real issue here, and if there is one, how can it be addressed.

C. What the Employer Health Insurance Mandate Says

For better or worse, the US health care insurance system is built around health plans normally provided to workers through their place of employment, as part of their overall wage compensation package. The system began during World War II and has expanded since, supported through substantial tax advantages. By now, health insurance provision is close to universal among large employers, but substantially less so among small private firms:

| Share of Private Firms Offering Health Insurance – 2013 |

|

|

|

| < 10 employees |

28.0% |

|

| 10 to 24 employees |

55.3% |

|

| 25 to 99 employees |

77.2% |

|

| 100 to 999 employees |

93.4% |

|

| ≥ 1000 employees |

99.3% |

|

|

|

|

| < 50 employees |

34.8% |

|

| ≥ 50 employees |

95.7% |

|

|

|

|

| All private employees |

84.9% |

|

|

|

|

| Source: MEPS, Tables I.A.2 and I.B.2 (2013) |

Overall, 84.9% of private sector employees are in firms that offer health insurance as part of their wage packages. And 96% of firms with more than just 50 employees offer health insurance.

The Affordable Care Act built on this and did not replace it. Liberals (including myself) would have preferred moving to a system where Medicare would be extended to cover the entire population rather than just those over age 65. Medicare is an efficient and well managed program, and as an earlier post in this blog discussed, its administrative expenses come to only 2.1% of the benefits paid. In contrast, administrative costs (including profits) of private health insurance are seven times higher at 14.0% of benefits paid, and an even higher 18.6% of benefits paid in the privately administered Medicare Advantage plans.

But Obama agreed instead to support an approach first proposed by the conservative Heritage Foundation, which was then put forward by Republicans in Congress as their alternative to the health reforms proposed by the Clinton administration (coming out of the task force Hillary Clinton chaired), and which was later adopted in Massachusetts when Mitt Romney was governor. These plans were built around keeping the existing employer-based provision of health insurance for most of those employed, but to complement this with markets where individuals could purchase health insurance directly if they did not have employer-based coverage, coupled with an individual mandate to buy such health insurance. The individual mandate is necessary to counter what would otherwise be a resulting death spiral of health insurance plans if everyone is granted access (including those with pre-existing conditions) but only the sick then purchased health insurance (for a description and discussion, see this earlier Econ 101 blog post).

It was not unreasonable to believe that the Republicans would not oppose a plan whose origins lies in their own earlier proposals, but that was not to be.

As noted, the individual mandate is necessary to avoid death spirals in health insurance plans for individuals. Complementing this, an employer mandate to offer health insurance to their employees is necessary to counter what could otherwise be a “race to the bottom”. If certain firms did not support such health insurance for their employees, thus reducing the cost to them of their workers, they could undercut competitors who did provide good health insurance support. It could lead to a race to the bottom. While not yet widespread in the US, especially for larger firms (see the table above), there has been increasing competitive pressure in the US over the last couple of decades to cut such health insurance support. An increasing number of employers have done so.

Thus the ACA includes an employer mandate to complement the individual mandate. However, while the individual mandate went into effect on January 1, 2014, the employer mandate has been twice delayed, and has now (as of January 1, 2015) gone into effect for firms employing 100 of more full time equivalent employees, and will go into effect on January 1, 2016, for firms employing 50 or more full time equivalent employees. It is this provision that the Republicans in Congress are now trying to subvert.

The charge by Paul Ryan and others has been that medium to small size firms have been cutting the hours of their employees to shift the workers from a full-time classification to a part-time one. The aim, they say, has been to reduce the number of their full time workers to below 50 so as to avoid the employer mandate. For example, in a recent opinion piece published in USA Today, Congressman Ryan wrote: “The law requires employers with more than 50 full-time employees to give them health insurance. But because the law defines “full time” as 30 hours or more, employers are keeping employees below that threshold to avoid the mandate entirely.”

However, that is not what the law says. Precisely to avoid such an incentive, the boundaries on the size of a firm subject to the employer mandate is defined in terms of full time equivalent workers (whether 50 or 100). That is, if a job is split from one full time worker to two half time workers, the number of full time equivalent workers is unchanged. The two half time workers count as one full time worker for the purposes of the statute. Cutting back on the number of hours of individual workers to make them part time will not change the status of the firm when the total hours of labor to produce whatever the firm is producing remains unchanged. And it would be foolish for a firm to produce and sell less when the demand exists for such sales, simply to avoid this mandate.

There is, however, a critically important issue here which Ryan and his colleagues have not discussed. While splitting jobs of full time workers into multiple part time jobs will not change the status of the firm on whether it is subject to the employer mandate, shifting workers from full time to part time status does affect whether the firm would be required to include health insurance as part of their wage compensation package. Firms subject to the mandate must offer an affordable health insurance plan available to at least 95% of full time (not full time equivalent) workers, or pay a fee. The fee (of up to $2,000 per year per worker, less 30 workers per firm) is designed to partially offset (and only very partially offset) the cost of health insurance that they are shifting to others.

But such health insurance typically only is provided to full time workers. This is true even for giant corporations. Hence a firm can avoid making health insurance available to its workers by shifting them from full time to part time status. This has always been the case, and is indeed a problem.

The Affordable Care Act addresses the issue only partially and tangentially. By including a definition of what constitutes full time work at 30 hours a week or more, the ACA reduces the incentive to shift workers from the traditional 40 hours per week for full time work, to just under 40 hours in order to avoid providing health insurance cover. A firm would need to cut a normal worker’s hours to below 30 hours per week to avoid providing health insurance, and is unlikely to do that for its regular work force. But by moving the dividing line up to 40 hours per week, as the Republican legislation passed on January 8 would do, one opens up a loophole for firms to reduce worker hours from 40 to say 39 per week (or 39 1/2 or even 39.99 I would suppose). Firms would be able easily to avoid offering health insurance to what are in reality their regular, full time, workers; use this to undercut competitors who do offer such insurance; and thus spark a race to the bottom on health insurance coverage in those industries.

D. Addressing the Problem of Health Insurance for Part Time Workers

As noted above, the ACA does not do much to address the problem of part time workers receiving nothing from their employers for the health insurance everyone needs. Setting the floor at 30 hours per week helps by ensuring workers close to the traditional 40 hour workweek will receive an employer contribution to their health insurance, and avoids the incentive to shift workers from 40 hours per week to just a bit below. But part time workers of less than 30 hours per week will still normally receive nothing from their employer to help cover their health insurance. And it creates an incentive for employers to structure positions as two workers at 20 hours per week, say, than one at 40. While whether or not the firm was subject to the employer mandate would not be affected (since it is expressed in terms of full time equivalent workers), whether or not the firms would need to provide anything in terms of health insurance would be affected.

But there is a way to address this, now that the individual health insurance marketplaces are operational under the ACA. All firms could be required to contribute an amount for their part time workers proportional to the hours of such part time work to what full time work would be. That is, if two workers are each working half time, the firm would contribute an amount of 50% (for each) of the cost of the employer contribution to the health insurance for one full time worker. The total cost would be the same whether the firm employed one full time or two half time workers. There would also then not be an incentive to split jobs from full time workers to multiple part time workers.

The employer contribution to the part time worker’s health insurance costs would then be paid, along with taxes such as for Social Security or Medicare, to the government in the name of the specific part time worker. These funds would then be used as a partial pay down of the costs of that worker purchasing health insurance on the individual health insurance market exchanges set up under the ACA. And while other splits could be considered, I would recommend that those funds would be split half and half between what the worker would need to pay on the exchange for his or her health plan, and what the government subsidy would provide.

A simple numerical example may help clarify this. Using made up numbers, suppose the full monthly cost of a standard (Silver level) health insurance plan on the individual exchange where the worker resides is $400. Assume also that at the current income level of this (part time) worker, the government subsidy for such insurance would be $200 per month, while the worker would pay $200 per month. Now assume that firms would be required to pay proportional shares of what they provide to full time workers for their health insurance, and that this would come to $100 per month for this part time worker. This would be split half and half between what the government subsidy would be and what the worker would pay, so under the new approach the government would provide $150, the worker would pay $150, and the funds coming from the firm would cover $100, summing to the $400 total cost.

A few specifics to note: Many part time workers hold down multiple jobs. They would receive for their “account” the total proportional amounts from all of their employers. Many part time workers are also part of married couples. There could be a household account into which all the sums were paid (for each family member), which could be used to purchase a family health plan on the exchanges. In the event that the family was not purchasing insurance through the exchange (perhaps, for example, because the spouse worked at a firm providing family coverage), the amount paid by the firm for the part time worker would be returned to the firm (or canceled from the start).

And if the total amounts paid in from the full set of employers for that individual (or family) led to the government subsidy falling all the way to zero, any excess would be allocated to what the individual would pay for the insurance. This could be common in cases where the family income of the part time worker was close to, or above, the income limit on which government subsidies are provided.

It is only with the advent of the individual health insurance exchanges that this method for covering part time workers became possible. Previously, firms were not in a position to purchase half of an insurance policy for a half time worker. But now they can contribute an amount equal to half the cost, with this then used to help purchase coverage on the individual marketplace exchanges.

Note also that with this reform, it would matter less whether full time work was defined as 30 hours per week or 40 hours per week or whatever. I would recommend keeping the 30 hour per week boundary as it would be a factor in determining what the employer contribution would be. But it would not be as critical as now, where the boundary determines whether 100% of the employer share of the health insurance cost is paid or 0% is paid. There would be a smooth transition (a worker of 39 hours when 40 hours is defined as the standard would still receive 39/40 of the payment, and not zero), without a drop straight to zero.

There would also be no reason to limit this extension of the employer mandate only to firms with 50 (or 100) or more full time equivalent workers. All firms should make such a contribution to covering the cost of their workers’ health insurance needs, just as they all make a contribution to Social Security and Medicare taxes. Indeed firms of whatever size (although this will soon apply only to firms with less than 50 full time equivalent workers) that do not have any health insurance plan for their staff should participate. The amounts paid could be set as a proportion to the cost of the medium Silver level plan available on the individual health insurance exchanges in their area.

Undoubtedly, there will be assertions by the Republicans that requiring such a contribution to health insurance costs for their part time workers will lead to an end to such jobs. This would be similar to the arguments they have made that raising the minimum wage will lead to higher unemployment of lower paid workers, and arguments that were made earlier that paying Social Security taxes would lead to higher unemployment. But as was discussed in an earlier blog post, there is no evidence that increases in the minimum wage in the magnitudes that have been discussed have led to such higher unemployment. Ensuring firms contribute proportionally to the health insurance costs of their part time workers would not either.

You must be logged in to post a comment.