A. Introduction, and a Brief Aside on the Macro Issues

While there is much we do not yet know on what economic policies Donald Trump will pursue (he said many things in his campaign, but they were often contradictory), one thing we can be sure of is that there will be a major tax cut. Republicans in Congress (led by Paul Ryan) and in the Senator want the same. And they along with Trump insist that the cuts in tax rates will spur a sharp jump in GDP growth, with the result that net tax revenues in the end will not fall by all that much.

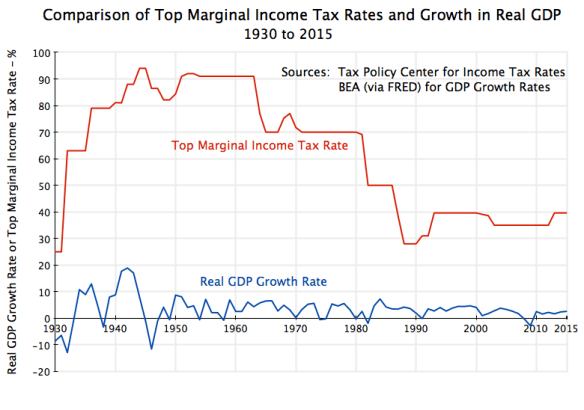

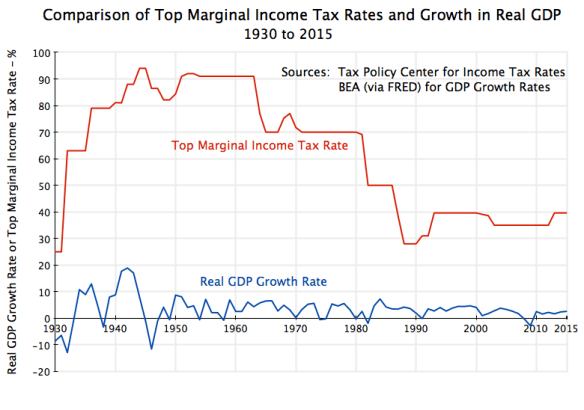

But do tax cuts spur growth? The chart above suggests not. Marginal tax rates of those in the top income brackets have come down sharply since the 1950s and early 1960s, when they exceeded 90%. They reached as low as 28% during the later Reagan years and 35% during the administration of George W. Bush. But GDP growth did not jump to some higher rate as a result.

This Econ 101 post will discuss the economics on why this is actually what one should expect. It will focus on the microeconomics behind this, as the case for income tax cuts is normally presented by the so-called “supply siders” as a micro story of incentives. The macro case for tax cuts is different. Briefly, in times of high unemployment when the economy is suffering from insufficient demand in the aggregate to purchase all that could be produced if more labor were employed, a cut in income taxes might spur demand by households, as they would then have higher post-tax incomes to spend on consumption items. This increase in demand could then spur production and hence GDP.

Critically, this macro story depends on allowing the fiscal deficit to rise by there not being simultaneously a cut in government expenditures along with the tax cuts. If there is such a cut in government expenditures, demand may be reduced by as much as or even more than demand would be increased by households. But the economic plans of both Trump and Congressman (and Speaker) Paul Ryan do also call for large cuts in government expenditures. While both Trump and Ryan have called for government expenditures to increase on certain items, such as for defense, they still want a net overall reduction.

The net impact on demand will then depend on how large the government expenditure cuts would be relative to the tax cuts, and on the design of the income tax cuts. As was discussed in an earlier post on this blog on the size of the fiscal multiplier, If most of the income tax cuts go to those who are relatively well off, who will then save most or perhaps all of their tax windfall, there will be little or no macro stimulus from the tax cuts. Any government expenditure cuts on top of this would then lead not to a spur in growth, but rather to output growing more slowly or contracting. And the tax plan offered by Donald Trump in his campaign would indeed direct the bulk of the tax cuts to the extremely well off. A careful analysis by the non-partisan Tax Policy Center found that 71% of the tax cuts (in dollar value) from the overall plan (which includes cuts in corporate and other taxes as well) would go to the richest 5% of households (those earning $299,500 or more), 51% would go to the top 1% (those earning $774,300 or more), and fully 25% would go to the richest 0.1% (those earning $4.8 million or more).

[A side note: To give some perspective on how large these tax cuts for the rich would be, the 25% going to the richest 0.1% under Trump’s plan would total $1.5 trillion over the next ten years, under the Tax Policy Center estimates. By comparison, the total that the Congressional Budget Office projects would be spent on the food stamp program (now officially called SNAP) for the poor over this period would come to a bit below $700 billion (see the August 2016 CBO 10-year budget projections). That is, the tax breaks to be given under Trump’s tax plan to the top 0.1% (who have earnings of $4.8 million or more in a year) would be more than twice as large as would be spent on the entire food stamp program over the period. Yet the Republican position is that we have to cut the food stamp program because we do not have sufficient government revenues to support it.]

The macro consequences of tax cuts that mostly go to the already well off, accompanied by government expenditure cuts to try to offset the deficit impact, are likely therefore to lead not to a spur in growth but to the opposite.

The microeconomic story is separate, and the rest of this blog post will focus on the arguments there. Those who argue that cuts in income taxes will act as a spur to growth base their argument on what they see as the incentive effects. Income taxes are a tax on working, they argue, and if you tax income less, people will work longer hours. More will be produced, the economy will grow faster, and people will have higher incomes.

This micro argument is mistaken in numerous ways, however. This Econ 101 post will discuss why. There is the textbook economics, where it appears these “supply siders” forgot some of the basic economics they were taught in their introductory micro courses. But we should also recognize that the decision on how many hours to work each week goes beyond simply the economics. There are important common social practices (which can vary by the nature of the job, i.e. what is a normal work day, and what do you do to get promoted) and institutional structures (the 40 hour work week) which play an important and I suspect dominant role. This blog post will review some of them.

But first, what do we know from the data, and what does standard textbook economics say?

B. Start with the Data

It is always good first to look at what the data is telling us. There have been many sharp cuts in income tax rates over the last several decades, and also some increases. Did the economy grow faster after the tax cuts, and slower following the tax increases?

The chart at the top of this post indicates not. The chart shows what GDP growth was year by year since 1930 along with the top marginal income tax rate of each year. The top marginal income tax rate is the rate of tax that would be paid on an additional dollar of income by those in the highest income tax bracket. The top marginal income tax rate is taken by those favoring tax cuts as the most important tax rate to focus on. It is paid by the richest, and these individuals are seen as the “job creators” and hence play an especially important role under this point of view. But changes in the top rates also mark the times when there were normally more general tax cuts for the rest of the population as well, as cuts (or increases) in the top marginal rates were generally accompanied by cuts (or increases) in the other rates also. It can thus be taken as a good indicator of when tax rates changed and in what direction. Note also that the chart combines on one scale the annual GDP percentage growth rates and the marginal tax rate as a percentage of an extra dollar of income, which are two different percentage concepts. But the point is to compare the two.

As the chart shows, the top marginal income tax rate exceeded 90% in the 1950s and early 1960s. The top rate then came down sharply, to generally 70% until the Reagan tax cuts of the early 1980s, when they fell to 50% and ultimately to just 28%. They then rose under Clinton to almost 40%, fell under the Bush II tax cuts to 35%, and then returned under Obama to the rate of almost 40%.

Were GDP growth rates faster in the periods when the marginal tax rates were lower, and slower when the tax rates were higher? One cannot see any indication of it in the chart. Indeed, even though the highest marginal tax rates are now far below what they were in the 1950s and early 1960s, GDP growth over the last decade and a half has been less than it what was when tax rates were not just a little bit, but much much higher. If cuts in the marginal tax rates are supposed to spur growth, one would have expected to see a significant increase in growth between when the top rate exceeded 90% and where it is now at about 40%.

Indeed, while I would not argue that higher tax rates necessarily lead to faster growth, the data do in fact show higher tax rates being positively correlated with faster growth. That is, the economy grew faster in years when the tax rates were higher, not lower. A simple statistical regression of the GDP growth rate on the top marginal income tax rate of the year found that if the top marginal tax rate were 10% points higher, GDP growth was 0.57% points higher. Furthermore, the t-statistic (of 2.48) indicates that the correlation was statistically significant.

Again, I would not argue that higher tax rates lead to faster GDP growth. Rather, much more was going on with the economy over this period which likely explains the correlation. But the data do indicate that very high top marginal income tax rates, even over 90%, were not a hindrance to growth. And there is clearly no support in the evidence that lower tax rates lead to faster growth.

The chart above focuses on the long-term impacts, and does not find any indication that tax cuts have led to faster growth. An earlier post on this blog looked at the more immediate impacts of such tax rates cuts or increases, focussing on the impacts over the next several years following major tax rate changes. It compared what happened to output and employment (as well as what happened to tax revenues and to the fiscal deficit) in the immediate years following the Reagan and Bush II tax cuts, and following the Clinton and Obama tax increases. What it found was that growth in output and employment, and in fiscal revenues, were faster following the Clinton and Obama tax increases than following the Reagan and Bush II tax cuts. And not surprisingly given this, the fiscal deficit got worse under Reagan and Bush II following their tax cuts, and improved following the Clinton and Obama tax increases.

C. The Economics of the Impact of Tax Rates on Work Effort

The “supply siders” who argue that cuts in income taxes will lead to faster growth base their case on what might seem (at least to them) simple common sense. They say that if you tax something, you will produce less of it. Tax it less, and you will produce more of it. And they say this applies to work effort. Income taxes are a tax on work. Lower income tax rates will then lead to greater work effort, they argue, and hence to more production and hence to more growth. GDP growth rates will rise.

But this is wrong, at several levels. One can start with some simple math. The argument confuses what would be (by their argument) a one-time step-up in production, with an increase in growth rates. Suppose that tax rates are cut and that as a result, everyone decides that at the new tax rates they will choose to work 42 hours a week rather than 40 hours a week before. Assuming productivity is unchanged (actually it would likely fall a bit), this would lead to a 5% increase in production. But this would be a one time increase. GDP would jump 5% in the first year, but would then grow at the same rate as it had before. There would be no permanent increase in the rate of growth, as the supply siders assert. This is just simple high school math. A one time increase is not the same as a permanent increase in the rate of growth.

But even leaving this aside, the supply sider argument ignores some basic economics taught in introductory microeconomics classes. Focussing just on the economics, what would be expected to happen if marginal income tax rates are cut? It is true that there will be what economists call “substitution effects”, where workers may well wish to work longer hours if their after-tax income from work rises due to a cut in marginal tax rates. But the changes will also be accompanied by what economists call “income effects”. Worker after-tax incomes will change both because of the tax rate changes and because of any differences in the hours they work. And these income effects will lead workers to want to work fewer hours. The income and substitution effects will work in opposite directions, and the net impact of the two is not clear. They could cancel each other out.

What are the income effects, and why would they lead to less of an incentive to work greater hours if the tax rate falls?:

a) First, one must keep in mind that the aim of working is to earn an income, and that hours spent working has a cost: One will have fewer hours at home each day to enjoy with your wife and kids, or for whatever other purposes you spend your non-working time. Economists lump this all under what they call “leisure”. Leisure is something desirable, and with all else equal, one would prefer more of it. Economists call this a “normal good”. With a higher income, you would want to buy more of it. And the way you buy more of it is by working fewer hours each day (at the cost of giving up the wages you would earn in those hours).

Hence, if taxes on income go down, so that your after-tax income at the original number of hours you work each day goes up, you will want to use at least some portion of this extra income to buy more time to spend at home. This is an income effect, and will go in the opposite direction of the substitution effect of higher after-tax wages leading to an incentive to work longer hours. We cannot say, a priori, whether the income effect or the substitution effect will dominate. It will vary by individual, based on their individual preferences, what their incomes are, and how many hours they were already working. It could go either way, and can only be addressed by looking at the data.

b) One should also recognize that one works to earn income for a reason, and one reason among many is to earn and save enough so that one can enjoy a comfortable retirement. But in standard economic theory, there is no reason to work obsessively before retirement so that one will then have such a large retirement “nest egg” as to enjoy a luxurious life style when one retires. Rather, the aim is to smooth out your consumption profile over both periods in your life.

Hence if income tax rates are cut, so that your after-tax incomes are higher, one will be able to save whatever one is aiming for for retirement, sooner. Hence it would be rational to reduce by some amount the hours one seeks to work each day, and enjoy them with your wife and kids at home, as your savings goals for retirement can still be met with those fewer hours of work. This is an income effect, and acts in the direction of reducing, rather than increasing, the number of hours one will choose to work if there is a general tax cut.

c) More generally, one should recognize that incomes are earned to achieve various aims. Some of these might be to cover fixed obligations, such as to pay on a mortgage or for student debt, and some might be quasi-fixed, such as to provide for a “comfortable” living standard for one’s family. If those aims are being met, then time spent at leisure (time spent at home with the family) may be especially attractive. In such circumstances, the income effect from tax cuts might be especially large, and sufficient to more than offset the substitution effects resulting from the change in the after-tax wage.

Income effects are real, and it is mistake to ignore them. They act in the opposite direction of the substitution effect, and will act to offset them. The offset might be partial, full, or even more than full. We cannot say simply by looking at the theory. Rather, one needs to look at the data. And as noted above, the data provdes no support to the suppostion that lower tax rates will lead to higher growth. Once one recognizes that there will be income effects as well as substitution effects, one can see that this should not be a surprise. It is fully consistent with the theory.

One can also show how the income and substitution effects work via some standard diagrams, involving indifference curves and budget constraints. These are used in most standard economics textbooks. However, I suspect that most readers will find such diagrams to be more confusing than enlightening. A verbal description, such as that above, will likely be more easy to follow. But for those who prefer such diagrams, the standard ones can be found at this web posting. Note, however, that there is a mistake (a typo I assume) in the key Figures 2A and 2B. The horizontal arrows (along the “leisure” axis) are pointed in the opposite direction of what they should (left instead of right in 2A and right instead of left in 2B). These errors indeed serve to emphasize how even the experts with such diagrams can get confused and miss simple typos.

D. But There is More to the Hours of Work Decision than Textbook Economics

The analysis above shows that the supply-siders, who stress microeconomic incentives as key, have forgotten half of the basic analysis taught in their introductory microeconomics classes. There are substitution effects resulting from a change in income tax rates, as the supply-siders argue, but there are also income effects which act in the opposite direction. The net effect is then not clear.

However, there is more to the working hours decision than the simple economics of income and substitution effects. There are social as well as institutional factors. It the real world, these other factors matter. And I suspect they matter a good deal more than the standard economics in explaining the observation that we do not see growth rates jumping upwards after the several rounds of major tax cuts of the last half century.

Such factors include the following:

a) For most jobs, a 40 hour work week is, at least formally, standard. For those earning hourly wages, any overtime above 40 hours is, by law, supposed to be compensated at 50% above their normal hourly wage. For workers in such jobs, one cannot generally go to your boss and tell him, in the event of an income tax increase say, that you now want to work only 39 1/2 hours each week. The hours are pretty much set for such workers.

b) There are of course other workers compensated by the hour who might work a variable number of hours each week at a job. These normally total well less than 40 hours a week. These would include many low wage occupations such as at fast food places, coffee shops, retail outlets, and similarly. But for many such workers, the number of hours they work each week is constrained not by the number of hours they want to work, but by the number of hours their employer will call them in for. A lower income tax rate might lead them to want to work even more hours, but when they are constrained already by the number of hours their employer will call them in for, there will be no change.

c) For salaried workers and professionals such as doctors, the number of hours they work each week is defined primarily by custom for their particular profession. They work the hours that others in that profession work, with this evolving over time for the profession as a whole. The hours worked are in general not determined by some individual negotiation between the professional and his or her supervisor, with this changing when income tax rates are changed. And many professionals indeed already work long hours (including medical doctors, where I worry whether they suffer from sleep deprivation given their often incredibly long hours).

d) The reason why one sees many professionals, including managers and others in office jobs, working such long hours probably has little to do with marginal income tax rates. Rather, they try to work longer than their co-workers, or at least not less, in order to get promoted. Promotion is a competition, where the individual seen as the best is the one who gets promoted. And the one seen as the best is often the one who works the longest each day. With the workers competing against each other, possibly only implicitly and not overtly recognized as such, there will be an upward spiral in the hours worked as each tries to out-do the other. This is ultimately constrained by social norms. Higher or lower income tax rates are not central here.

e) Finally, and not least, most of us do take pride in our work. We want to do it well, and this requires a certain amount of work effort. Taxes are not the central determinant in this.

E. Summary and Conclusion

I fully expect there to be a push to cut income tax rates early in the Trump presidency. The tax plan Trump set out during his campaign was similar to that proposed by House Speaker Paul Ryan, and both would cut rates sharply, especially for those who are already well off. They will argue that the cuts in tax rates will spur growth in GDP, and that as a consequence, the fiscal deficit will not increase much if at all.

There is, however, no evidence in the historical data that this will be the case. Income tax rates have been cut sharply since the Eisenhower years, when the top marginal income tax rate topped 90%, but growth rates did not jump higher following the successive rounds of cuts.

Tax cuts, if they are focused on those of lower to middle income, might serve as a macro stimulus if unemployment is significant. Such households would be likely to spend their extra income on consumption items rather than save it, and this extra household consumption demand can serve to spur production. But tax cuts that go primarily to the rich (as the tax cuts that have been proposed by Trump and Ryan would do), that are also accompanied by significant government expenditure cuts, will likely have a depressive rather than stimulative effect.

The supply-siders base their argument, however, for why tax cuts should lead to an increase in the growth rate of GDP, not on the macro effects but rather on what they believe will be the impact on microeconomic incentives. They argue that income taxes are a tax on work, and a reduction in the tax on work will lead to greater work effort.

They are, however, confused. What they describe is what economists call the substitution effect. That may well exist. But there are also income effects resulting from the changes in the tax rates, and these income effects will work in the opposite direction. The net impact is not clear, even if one keeps just to standard microeconomics. The net impact could be a wash. Indeed, the net impact could even be negative, leading to fewer hours worked when there is a cut in income taxes. One does not know a priori, and you need to look at the data. And there is no indication in the data that the sharp cuts in marginal tax rates over the last half century have led to higher rates of growth.

There is also more to the working hours decision than just textbook microeconomics. There are important social and institutional factors, which I suspect will dominate. And they do not depend on the marginal rates of income taxes.

But if you are making an economic argument, you should at least get the economics right.

You must be logged in to post a comment.