A. Introduction

One of the more important reasons many voters are upset is that buying a home has become increasingly difficult. Not enough homes are being built, and with the need for housing (one has to live somewhere), home prices have shot up to record levels. While they had also gone up in the housing bubble that peaked in 2006/7 and then crashed (leading to the economic and financial collapse of 2008), that was a demand-driven bubble. Mortgages were provided with very little down and with scant attention to affordability to borrowers who could not then repay them. This soon came crashing down, along with home prices.

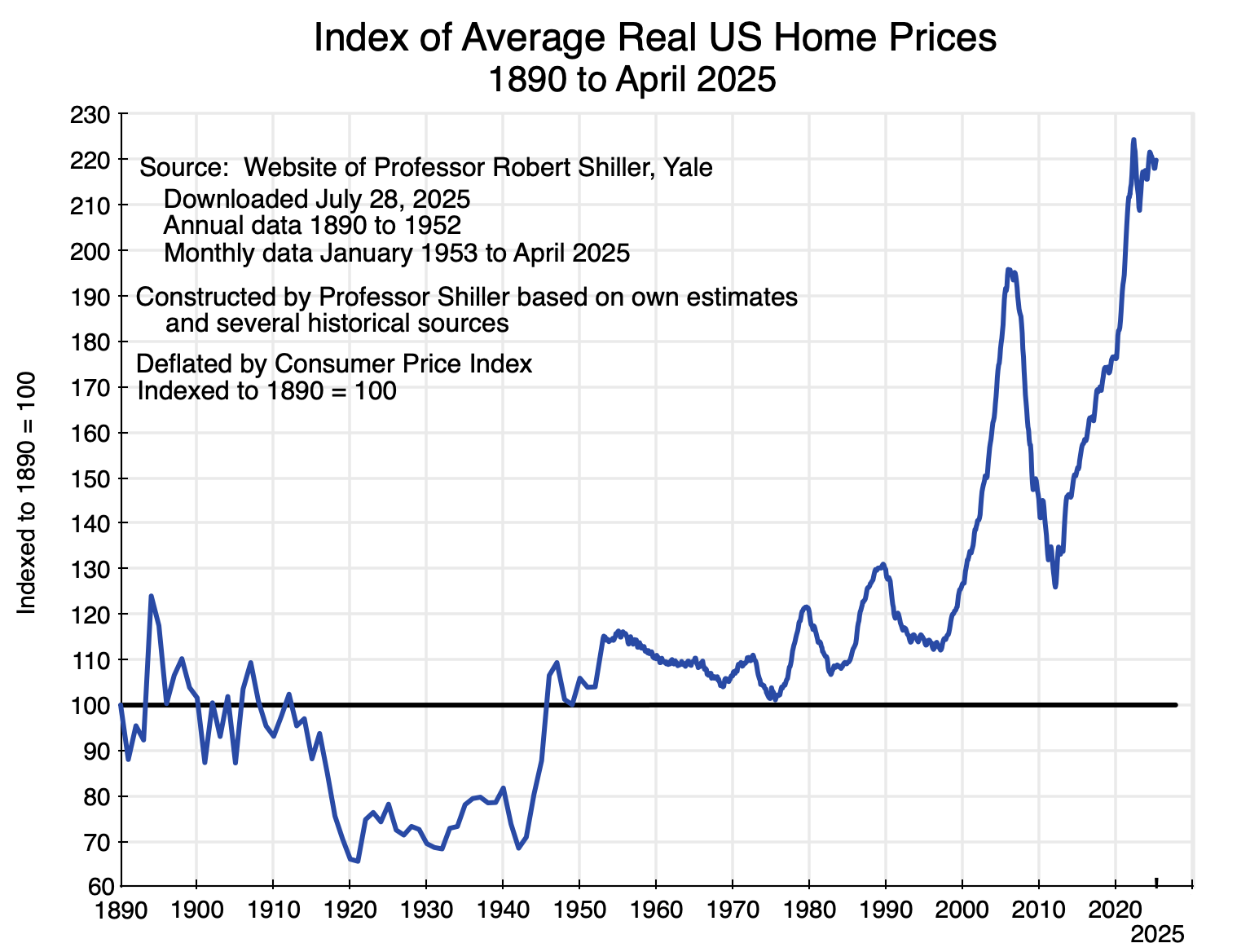

The recent spike in home prices is different. Not only are prices substantially higher now than at their pre-2008 peak, but they are also far higher (in real terms, not just nominal) than they have ever been in the US in data going back to 1890. See the chart above. For over a century (i.e. from 1890 to 2000), real home prices fluctuated between index values of around 70 on the low side and at most 130 on the high side (where the price in 1890 = 100). They are now at 220. While homeowners can have good reason to be pleased by this rise in the value of their homes, those who are not homeowners see the rising prices as an ever-rising bar that will prevent them from ever being able to afford to buy a home. For good reason, they are upset.

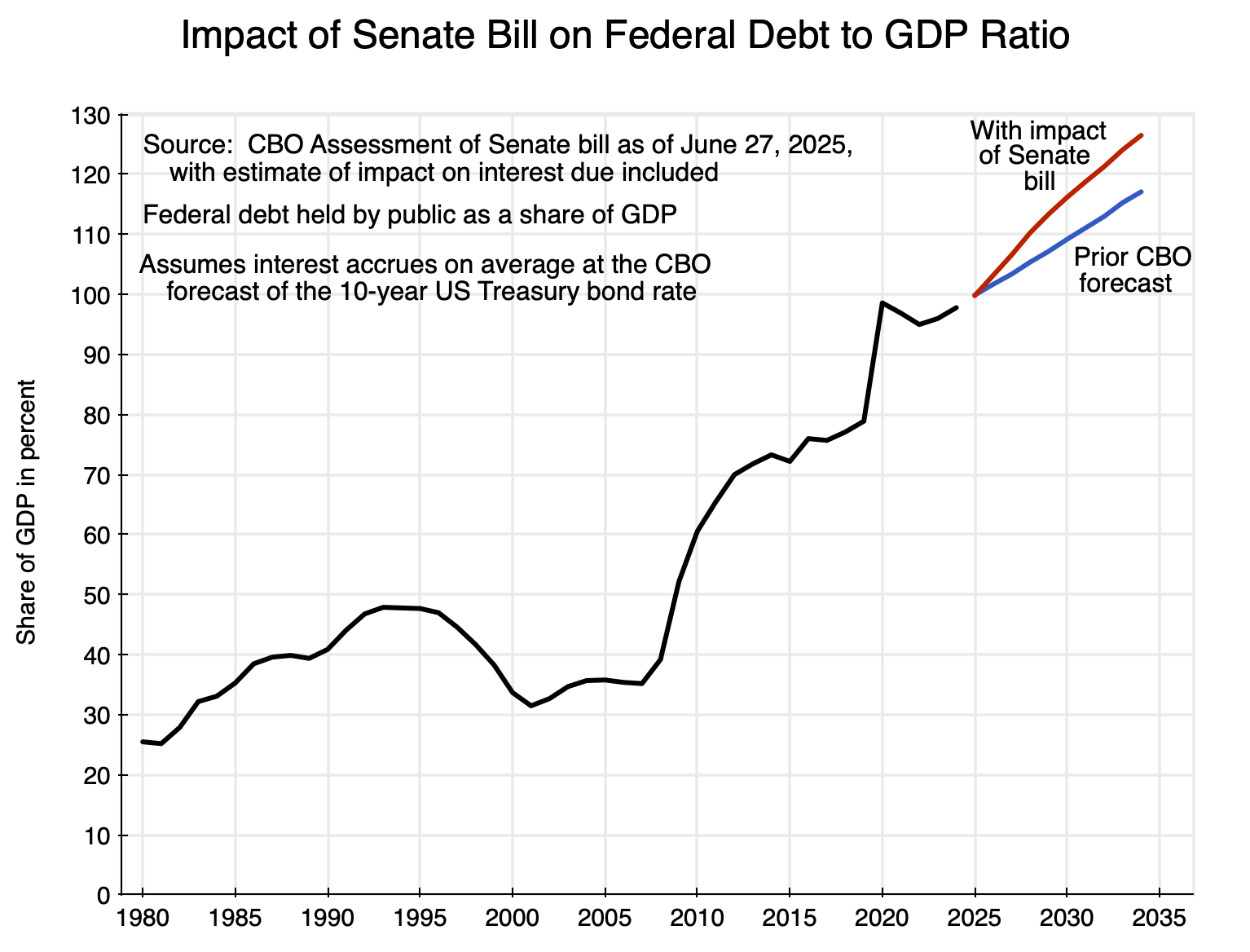

This post is the third in a series that have examined the economic factors behind why voters are upset. Earlier posts looked at the overall figures on the slowdown in growth (and hence in incomes) following the 2008 economic and financial collapse, and at the structural factors behind that slowdown (with roughly equal shares due to: 1) a slowdown in labor force growth as a consequence of an aging population; 2) a slowdown in private investment despite record high profits and slashing taxes on profits from 35% to 21% in Trump’s 2017 tax measure; and 3) a slowdown in the growth in productivity of the resulting labor and capital).

This post will examine the reasons behind the recent sharp rise in home prices. There are numerous home builders in the country, and with competition one might normally expect at least some to step in and build more homes to take advantage of those high prices. That has not happened, and the interesting – and important – question is why.

What we will find:

a) First, home prices in the US are at historic highs and are now far higher than where they have ever been (in real terms) going back to 1890 – 135 years ago.

b) Second, the number of homes being built has not been enough to keep up with the growing number of households in the country. But people have to live somewhere, so people do what they can to pay for the housing (whether owned or rented) they need. This pushes up the price of housing.

c) With those high prices, why are more homes not being built? What one reads in the news media is that home builders claim they cannot build enough and have to charge such high prices because they are facing higher costs themselves – of labor, lumber, and other inputs – and because of burdensome regulation.

d) If this were true, then the profitability of home building would be going down. With higher costs, profitability would fall. However, this has not been the case. The profitability of the major home builders is remarkably high.

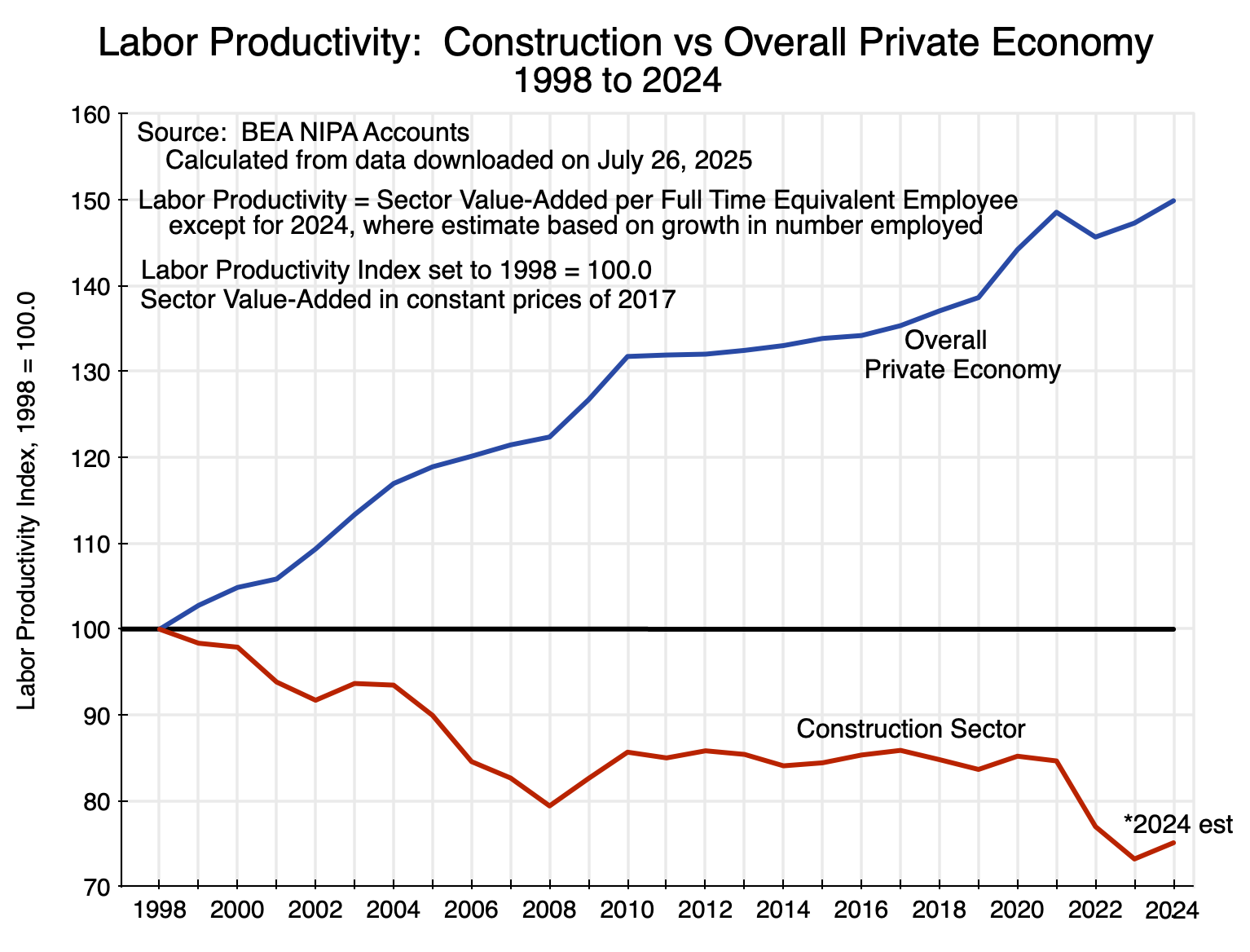

e) There is also the odd result that productivity in the construction sector (of which home building is a major part) has gone down in recent decades in absolute terms. Productivity almost always goes up, as productivity comes from knowledge of how to do things better. Over time, one learns more. The rate of increase in productivity can and does vary by sector, but what is puzzling is why it would go down in absolute terms. Yet the construction sector produced 25% less per unit of labor in 2024 than it did in 1998. Labor productivity in the overall private economy was 50% higher in 2024 than it was in 1998.

f) The question, then, is why has the construction of new homes fallen far short of what is needed despite the high profits the homebuilders are enjoying? With competition, one would expect that if some home builders do not build more, then others will step in and do it. The technology on how to build a home is not secret or proprietary, and at a national level there are hundreds if not thousands of firms building homes.

g) This has not happened. It can be explained by what we see at the local level, where one needs to recognize that the relevant market for home building is not national but local. Home building is not like making cars, for example, where one factory can serve the entire nation. What we will find is that at the level of local markets – metro areas – home building has become much more concentrated over the last couple of decades, with a limited number of firms in each metro area taking an increasing share of the metro area market. Homebuilders have been merging with each other or acquiring smaller firms, with the result that a small number of firms have grown to dominate the individual local markets. The market shares of the top firms in each local market have grown, even though there can be (and normally are) different sets of firms in the different local markets across the nation.

h) At a national level, therefore, the relatively modest market shares of individual home builders can make it look like the market for home building is diverse, with numerous builders each of whom is small compared to the overall national market. But the national market is not the relevant market for home building: local markets are. And at the local market level, a few firms dominate in each and their dominance has grown in recent decades.

i) By dominating their local markets, those few firms in each market can then have the market power to limit the building of new homes despite the high demand. They face little pressure to invest to develop greater capacity to build more homes, and little pressure to improve their productivity. Their productivity can fall in absolute terms – as has happened – yet their profitability can be high and indeed even grow despite that fall in productivity. Without the pressure of competition, they can charge high prices for the homes they do build and thus be highly profitable.

This post will cover each of these points in the sections below, documenting them and illustrating the developments through a series of charts.

An annex to this post will then present, through basic supply and demand diagrams, an analysis of what to expect under such market conditions. Economists love supply and demand diagrams, but few others do. You will not miss much by skipping the annex, but some may enjoy the exercise of working through the charts.

Cases such as this are called instances of “monopolistic competition” by economists. The annex will first review the base case of firm-level supply and demand under conditions of perfect competition and, alternatively, then of monopolistic competition where there are limits to the entry of new competitors in those markets. Under each, we will see how much the firm will choose to build (the answer is they will choose to build less – possibly far less – under conditions of monopolistic competition than they would under conditions of perfect competition), the price the firm will charge for what it produces (higher – and possibly far higher – than they would if they faced more competition), and the resulting profits (higher as well – and again possibly far higher). All this can be found in any basic introductory microeconomics textbook.

But the conditions in the local housing markets in the US then deviate from those covered in the standard textbooks. In the standard textbook case, the high profitability in a market with monopolistic competition will induce at least some new firms to enter the market and provide a similar product. After price and quantity adjustments, no exceptional profits will then be earned. But in the local housing markets of the US, concentration among home-building firms has increased over the last couple of decades, not decreased. There is now less competition, rather than more.

The annex will show that under such conditions the exceptional profits will then grow even higher with that increase in market concentration. And in a third case, the annex will show that with both growing market concentration and growing demand for the product (housing), the exceptional profits will grow yet higher again.

B. The High Price of Homes

Home prices in the US are exceptionally high. The chart at the top of this post provides an estimate of real home prices (adjusted based on the general CPI) for the period from 1890 (with an index value set equal to 100) through to April 2025. The data were assembled by Professor Robert Shiller of Yale, and was originally constructed for his book Irrational Exuberance. The data in it is now updated monthly, and is available at Shiller’s personal website.

The series was assembled by Shiller by splicing together the estimates of several researchers, with the data through 1952 on an annual basis and since then on a monthly basis. The data from April 1975 onward is from the Case-Shiller house price index that Shiller originally developed along with Karl Case and other colleagues, and is now a product of S&P/Corelogic. While there will be more uncertainty in such data as one goes back in time, the Case-Shiller home price indices are carefully done, and it is the data for the last half-century (i.e. 1975 to now) that are of most interest to us. Note that the prices incorporate adjustments to reflect changes in the quality of the homes being sold. The Case-Shiller index does this by tracking the repeat sale prices of individual homes, adjusted for the cost of major renovations. But it would have been increasingly difficult to do this accurately the further one goes back in time.

But it is the overall trends that are of most interest, plus what has happened to such home prices in recent years. And the story is clear: Real home prices fluctuated in a relatively narrow range (narrow given the length of time being considered) of between index values of 70 and 130 in the 110 years between 1890 and 2000 (with 1890 = 100.0).

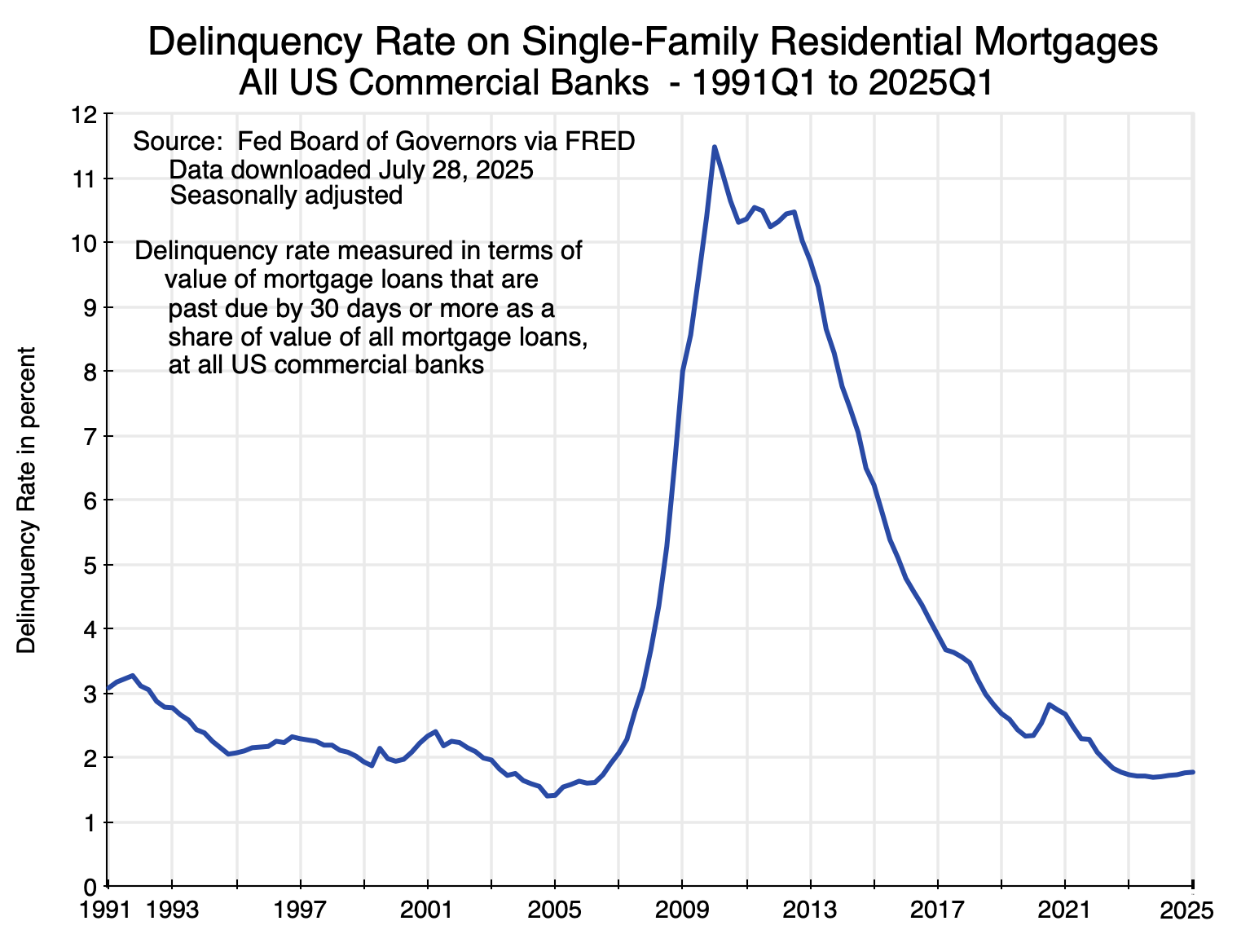

This then changed in the period leading up to 2006. Home prices in real terms reached a peak of 195 in 2006 and then fell – at first slowly and then quickly – as the demand-led housing bubble burst. Financial markets discovered that home prices – driven as they had been by easy mortgage lending boosting demand – would not keep going up forever, as mortgage delinquency rates rose:

As home prices fell, the housing assets that backed the mortgages would not suffice to allow for a full recovery of what had been lent to the borrowers now going into default. Mortgage lenders became more careful, the effective demand for housing fell, and home prices crashed.

The current run-up in home prices is different. Mortgage delinquency rates, as seen in Chart 2, are now roughly where they were before the run-up to the 2007/08 mortgage-led crisis. Easy mortgage lending is not now driving up home prices. Rather, and as we will see in the next section, the cause has been supply-led rather than demand-led. Home building has not kept pace with the growing number of households.

C. Not Enough Homes Are Being Built

One can look at the adequacy of the number of new homes being built each year – adding to the existing stock of housing – in a number of different ways. We will examine several in this section, and they all point to the problem of not enough homes being built.

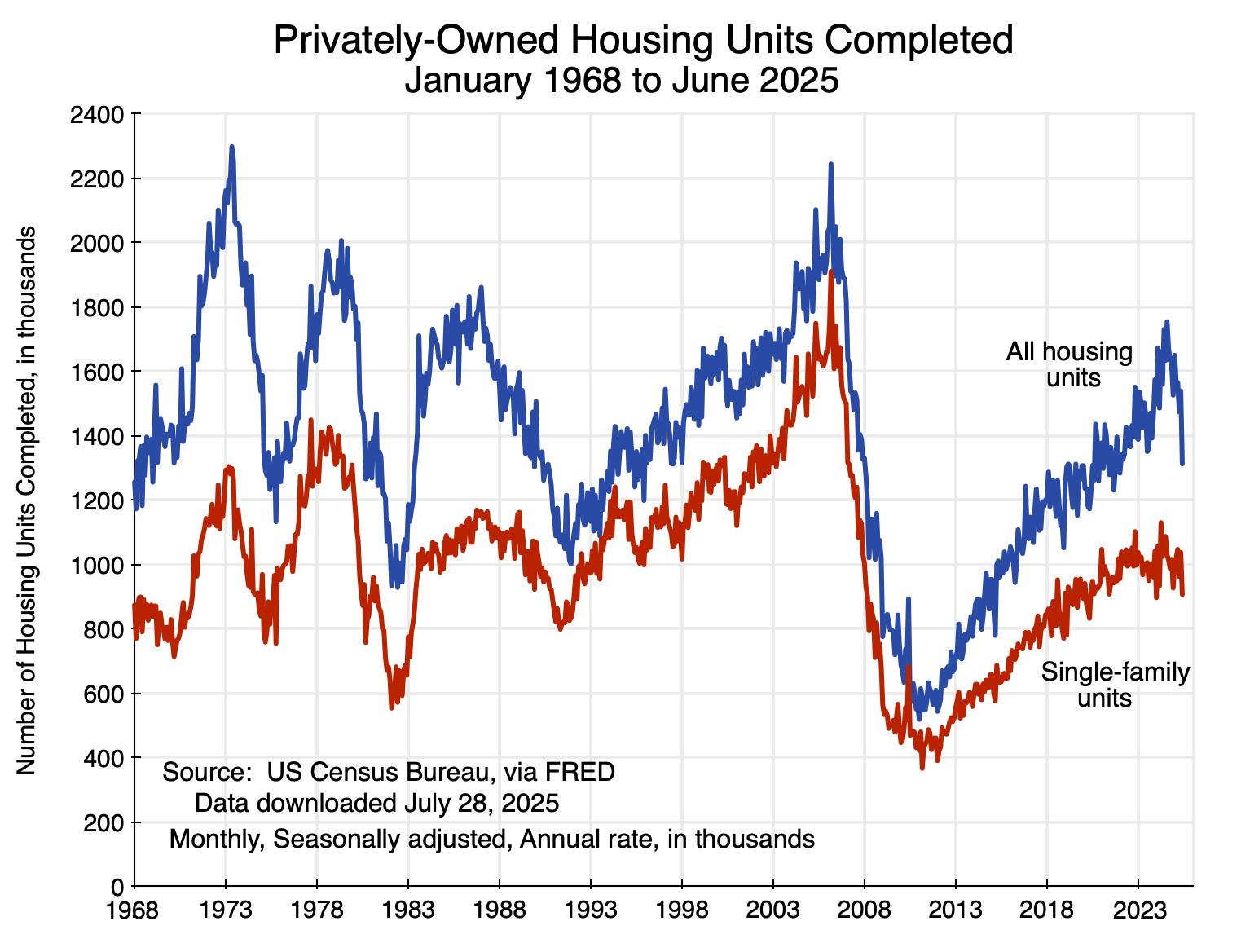

First, there are figures on the number of housing units being completed each month:

The number being completed has fluctuated widely over the years but fell especially sharply following the bursting of the housing bubble in 2007.

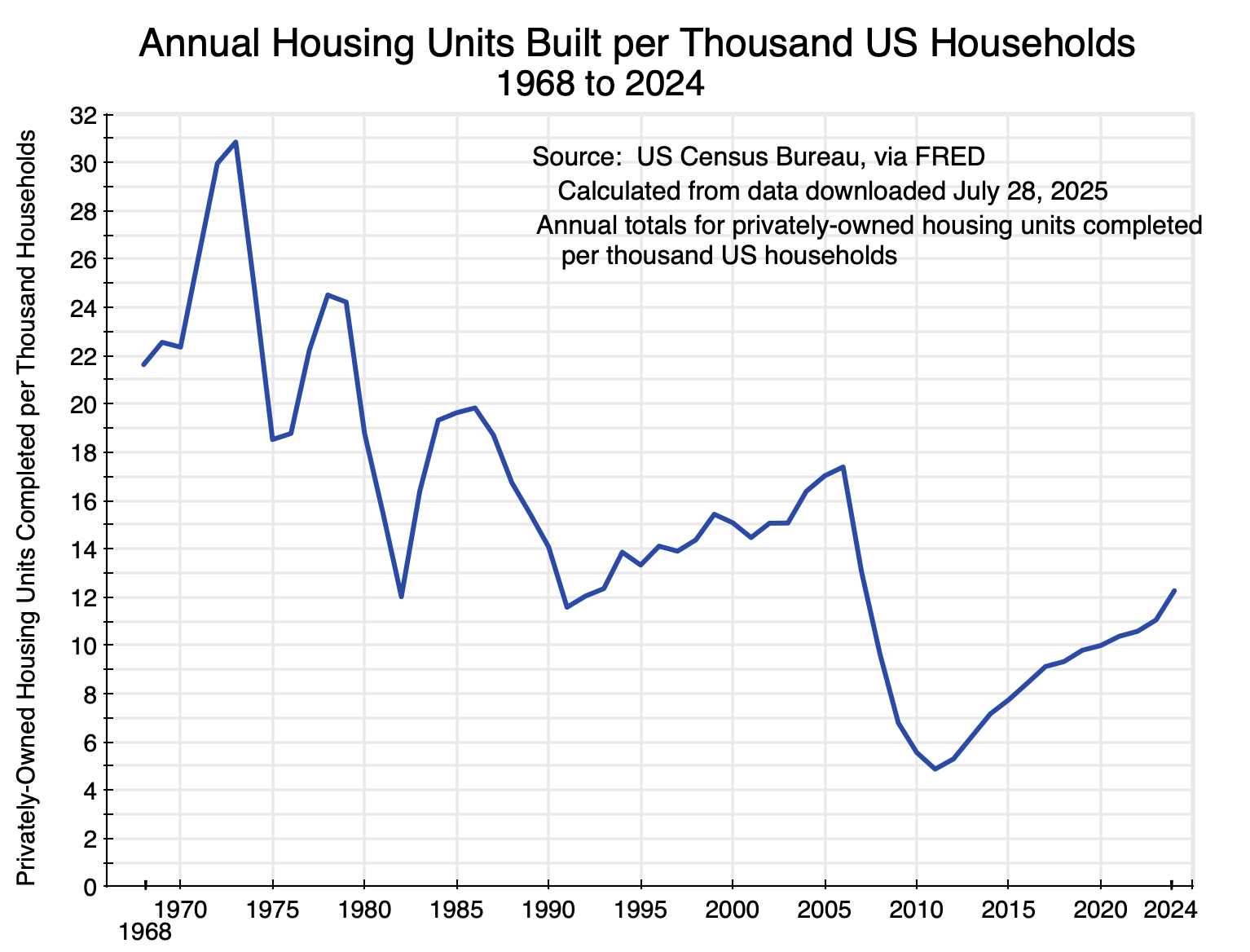

But the figures on the absolute number of new homes built each period tell only part of the story, as the population of the US has grown substantially as have the number of households. There were 60 million households in the US in 1968 but more than double that now with 132 million households as of 2024. The number of new housing units being built each year per thousand US households has come down sharply:

The 10-year average number of new housing units being built each year per thousand households was 24.2 in the 1970s. The most recent 10-year average (ending in 2024) was just 9.9 (60% less than in the 1970s), and hit a low of just 7.1 in 2018 (70% less). Home building has not kept up.

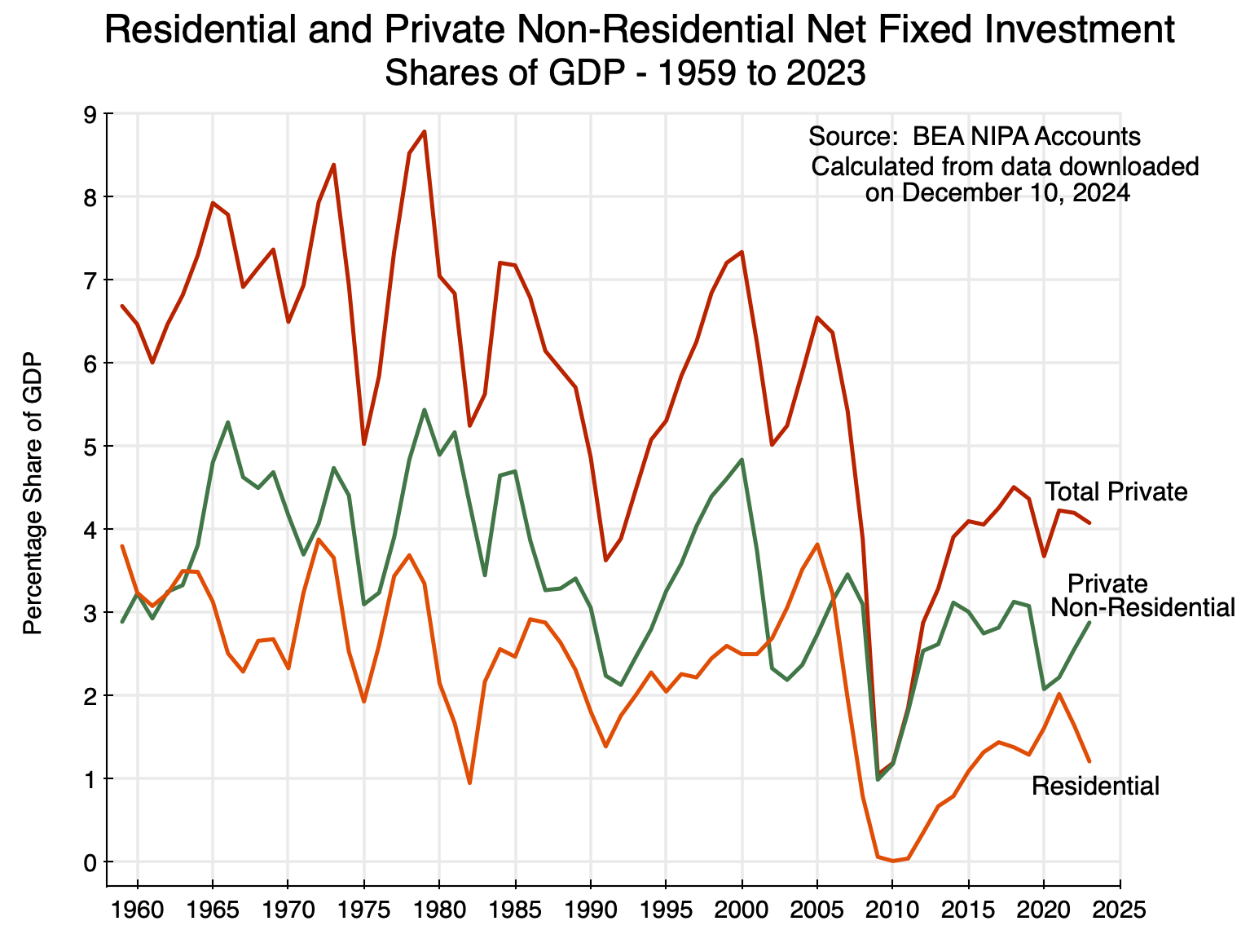

The fall in residential investment is also clear in the National Income and Product Accounts (NIPA, and more commonly referred to as the GDP accounts, produced by the Bureau of Economic Analysis. Net residential fixed investment (i.e. in housing, and “net” refers to net of depreciation) as a share of GDP has fluctuated widely in recent decades, but around a declining trend:

I have included in the chart the share of private non-residential net fixed investment as a share of GDP for context. It has also been declining, although not by as much as net investment in residential fixed assets. Net residential investment fell to essentially zero as a share of GDP in 2009-11, following the bursting of the housing bubble, and then recovered to only between 1 and 2% of GDP. As of 2023 it was around 1% of GDP – well below where it was in the 1960s and 70s.

[Side note: This and the following chart were prepared in December 2024, as part of my preparation for my earlier post on the slowdown in overall GDP growth. I then decided that the slowdown in housing investment should be addressed in a separate post – this one. But the underlying data – through 2023 here – are still the most recent available. They are updated only annually, and the data for 2024 will be released only in late September 2025.]

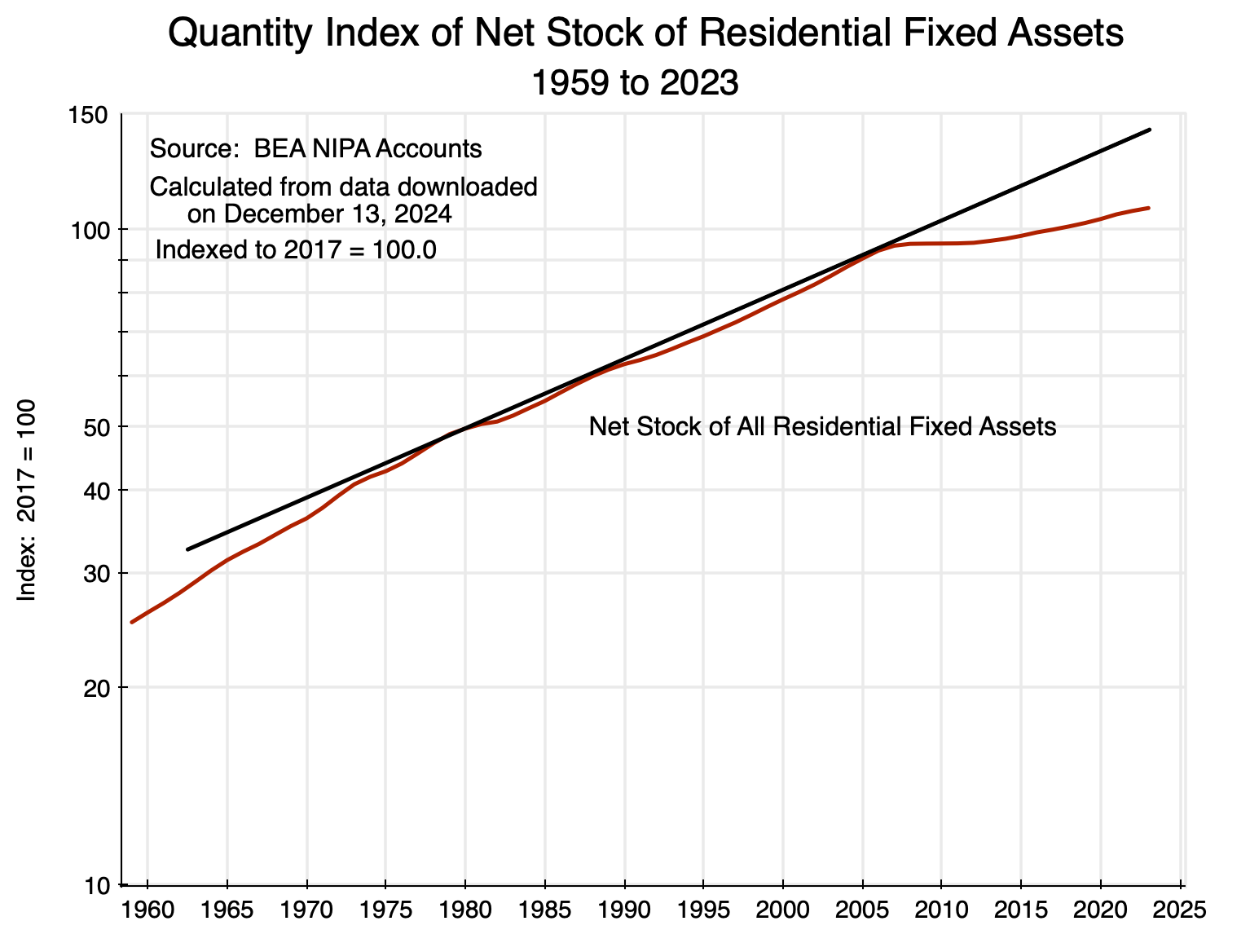

The growth in the resulting stock of residential fixed assets in real terms (i.e. the housing stock) was then:

The chart is on a logarithmic scale on the vertical axis. A straight line on a logarithmic scale will reflect a constant rate of growth (with that rate of growth equal to the slope of the line). The straight line in black is thus the trend growth in the stock of residential fixed assets between around 1980 and 2007. It closely tracks that growth over the 1980 to 2007 period, with little fluctuation around it. But then the growth in housing assets diverges sharply below the previous trend. The stock of housing would have been 32% higher in 2023 had it kept growing at its pre-2007 trend. That is huge. It should be no wonder that home prices were consequently bid up by so much.

While new home building has been slowing for some time in the US, it is noteworthy that the divergence from the previous trend in the real stock of residential fixed assets came only in 2008. That divergence was then sustained and the relative gap continues to widen. The increase in home prices under such conditions is not then surprising. But why have home builders not responded by building more new homes? If, as they often argue, they could not produce more because their costs had risen (costs of labor, materials, regulatory burdens, and other such costs), then their profitability would have gone down. But as we will see in the next section, profits have instead been high, and have indeed been exceptionally high for some time.

D. But Home Building is Highly Profitable

Possibly the best measure of whether the profitability of a firm has been increasing – and is expected to continue to do so – comes from observing the price of its publicly traded shares. Investors buy equity in firms based on their expected profitability, and they will pay prices that will rise faster over time than the prices of other possible investments when that profitability is (and is expected to be) increasing faster than others.

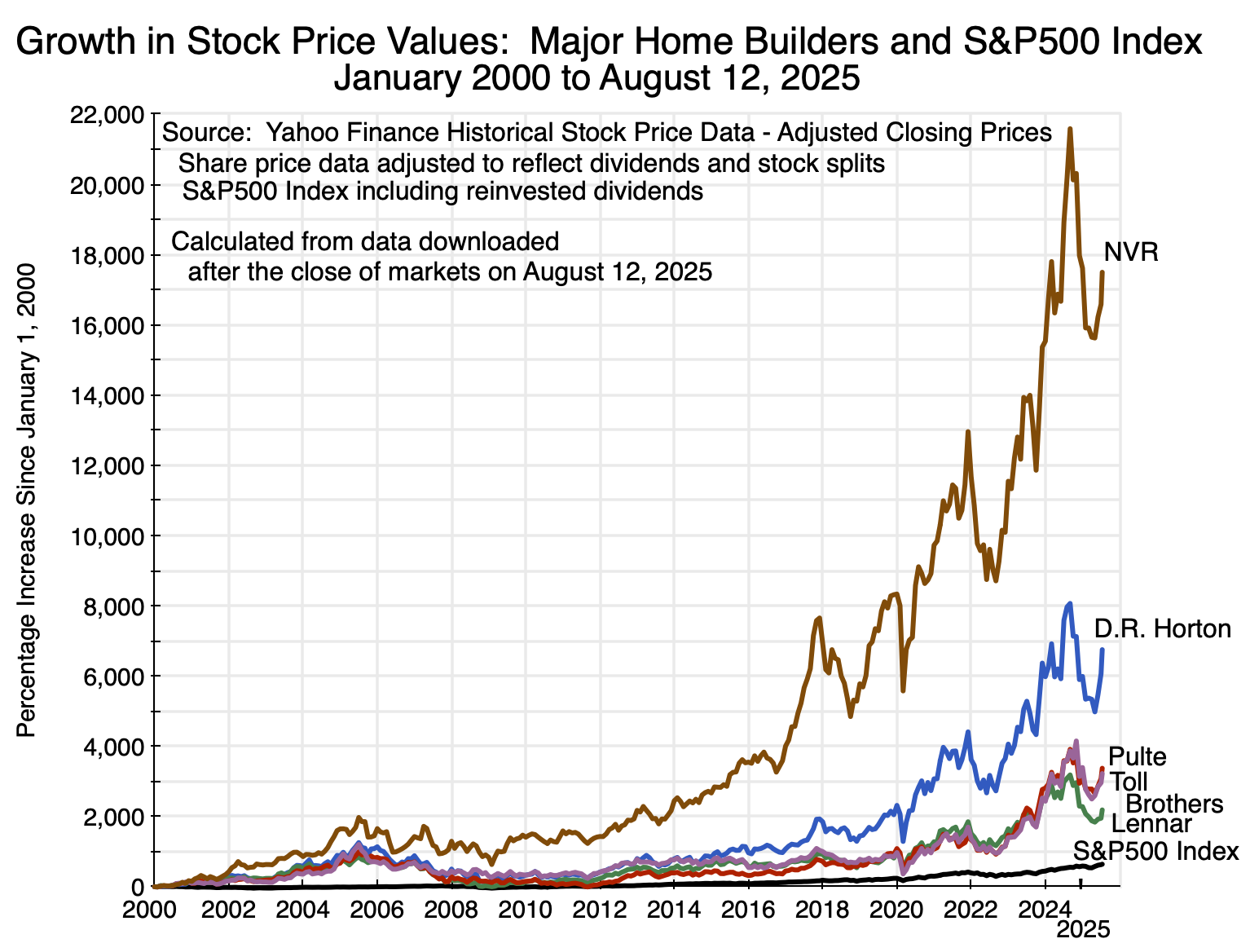

And the observed prices of what investors are willing to pay for equity in the major home builders have increased spectacularly:

The chart shows the percentage increases in the stock prices (including reinvested dividends and capital gain distributions, and adjusted for any stock splits) of the five largest homebuilders in the nation (in terms of gross revenues earned in 2024) over the more than 25 years from January 2000 to August 12, 2025. For comparison, the percentage increase in an investment in the S&P500 stock index (and again including reinvested dividends and any other distributions) over the same period is also shown. The equity price figures were obtained from Yahoo Finance historical stock data. For example, see here for the figures on D.R. Horton.

The figures for the resulting investment returns are summarized in this table:

Value of a $10,000 Investment Made in January 2000

|

Value as of August 12, 2025 |

Rate of Return |

|

| S&P500 | $74,279 | 8.2% |

| D.R. Horton | $685,108 | 18.0% |

| Lennar Corp | $228,805 | 13.0% |

| PulteGroup | $347,408 | 14.9% |

| NVR, Inc | $1,759,624 | 22.4% |

| Toll Brothers, Inc | $332,358 | 14.7% |

An investment of $10,000 in January 2000 in the S&P500 stock index would have grown to $74,279 as of August 12, 2025, for an annual rate of return of 8.2%. This is a nominal rate of return, but one can adjust for inflation by subtracting 2.6% – the average rate of inflation per annum over the period (as measured by the CPI).

An investment in the S&P500 index over the period – with a $10,000 investment rising to $74,279 – would have provided an excellent return. But a $10,000 investment over the same period in any of the large homebuilders would have been far better. A $10,000 investment in Lennar Corporation would have grown to almost $230,000. And that would have been the worst among the five. A $10,000 investment in NVR would have grown to over $1.7 million!

Furthermore, it appears that at least one prominent investor expects these excellent returns to continue. Berkshire Hathaway – with Warren Buffett as CEO – revealed this month through a regular filing with the SEC that it had recently made major investments in Lennar Corporation and D.R. Horton.

There is no evidence here that home builder profits have been squeezed in recent years by high costs, forcing them to cut back on their home building. Rather, the stock price data would be consistent with the opposite line of causation: That the reduction in the pace of housing being built (as seen since 2008) has led to much higher profits.

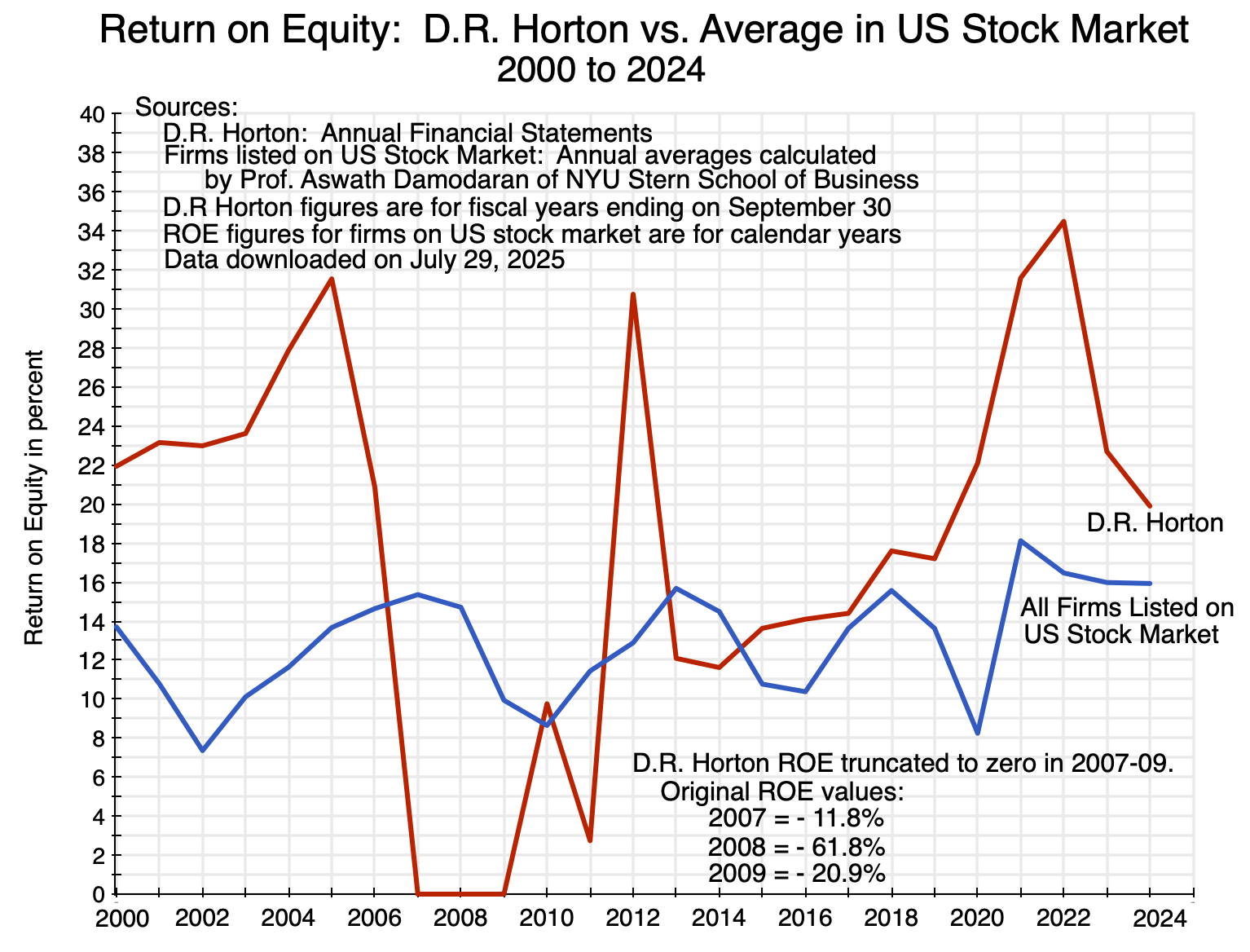

Another indication of profitability can be found in the income statements of the different home builders, with measures such as the return on equity (ROE) generated in any given year. I looked at the case of D.R. Horton – currently the largest home builder in the US in terms of the number of homes built each year (as well as in gross revenues). ROE figures can be found in the various annual reports of D.R. Horton. These were then compared to the overall average ROE figure of all US publicly traded firms (compiled annually by Professor Aswath Damodaran of NYU, for over 6,000 publicly traded firms on US stock exchanges):

With the major exception of negative returns in 2007-09 following the collapse of the housing price bubble, and a relatively low return in 2011, the return on equity of D.R. Horton has generally been higher than the average ROE of firms traded on US stock exchanges – and often far higher. The gap has been especially high in recent years (as it was earlier when the demand-led home price bubble was building up in the years before 2007). Home building has been a highly profitable activity.

The profitability of home building has remained exceptionally high in recent years. There is no evidence that rising home prices should be blamed on rising costs of materials, labor, regulatory burdens, or other such factors – as is often asserted. If rising costs were the cause, then the profitability of home builders would be low. They are not.

E. Profitability Has Been High Despite a Large Fall in Productivity

Another clue to what has been happening in the home building sector – with too few homes being built despite the exceptionally high profitability of home-building firms – can be found in how productivity in the sector has changed over time. One always expects productivity to grow over time, as productivity reflects knowledge (the knowledge of how best to build what one is building), and knowledge only goes in one direction. Knowledge is gained as one learns how to do things better, and whatever one knew before will presumably not be forgotten.

Yet remarkably, productivity in the construction sector has gone down over the past several decades, not up. Government statistics on this are unfortunately only available for the construction sector as a whole – not for residential construction (home building) alone. But residential construction is a major part of what is covered by the construction sector, accounting for 35% of it in 2023 (in value-added terms).

While productivity figures for residential construction alone are not available, the productivity growth figures for residential construction are almost certainly worse than what they were for construction as a whole. The remainder of construction includes activities such as the building of bridges, roads, and highways, as well as of office buildings and commercial structures. Those non-residential construction activities can make more extensive use of heavy equipment (such as bulldozers and excavators), tall cranes (for the building of multi-story office structures), and other such equipment that have gotten better over time. Building individual homes is smaller scale and more decentralized, and heavy equipment is not as helpful to productivity.

But productivity has declined over time even for the overall construction sector. In terms of simple labor productivity (what is produced in terms of the sector’s real value-added per employee, with those employed measured in full-time equivalent terms – i.e. with part-time workers included and weighted by their hours relative to full-time workers):

Labor productivity by sector can be calculated on a fully consistent basis for the construction sector only going back to 1998 in the current BEA statistics. There was a change in how sectors were defined in 1997/98, so the prior series are not always fully consistent with the more recent ones. But over the 26 years since 1998, labor productivity in the construction sector actually fell by 2023 to just 73% of what it was in 1998 and to 75% of what it was in 2024 (based on a 2024 estimate where I assumed employment of full-time equivalent workers grew at the same rate as the number of full-time workers – data on part-time workers are not yet available). The fall in productivity mostly came in two periods: the years leading up to 2008 (after which there was a partial recovery to 2010) and then again very recently in 2022 and 2023. Between 2010 and 2021 productivity in construction was flat, without the growth over time that one sees in other sectors.

In contrast, labor productivity for the overall private economy grew by 50% between 1998 and 2024 – an annual rate of growth of 1.7% a year. While the 1.7% per year might not appear to be high, it compounds over time. If labor productivity in construction had grown at the same pace as it had in the overall private economy, the construction sector in 2024 would have been producing twice as much per worker (=1.50/0.75) as it was.

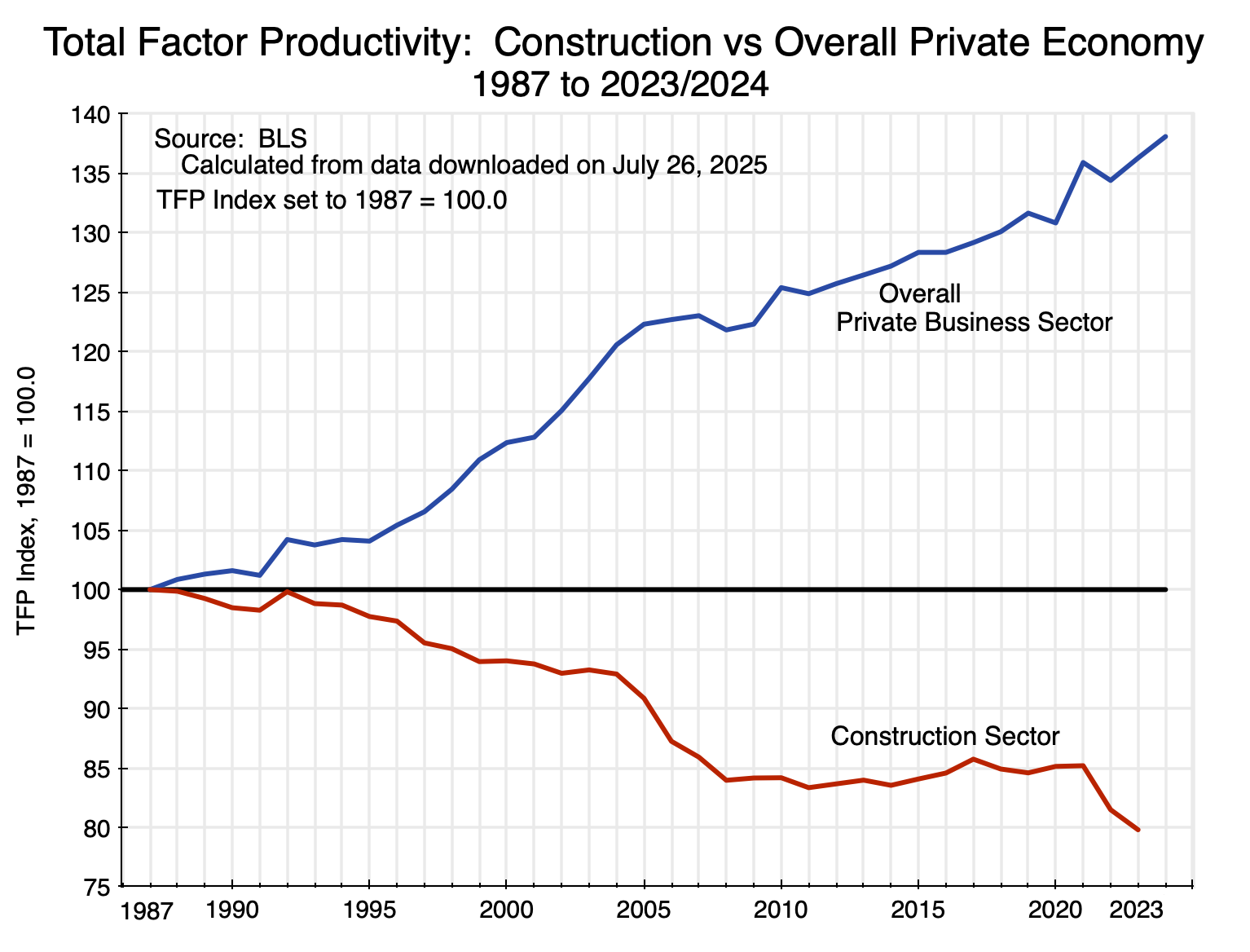

Labor productivity is simple to calculate as one only needs data on how much is produced in the sector and how many people are employed. For certain purposes it is also the more meaningful concept, e.g. when one is interested in living standards that are possible. But a more comprehensive measure of productivity will take into account other inputs used in production and in particular how much capital is employed (i.e. machinery and equipment, vehicles such as trucks, and so on). The Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) provides an estimate of such a concept, which is called total factor productivity (TFP) – how much is produced (in real value-added terms) per unit of labor and capital inputs together.

We again see a sharp divergence in recent decades between growth in productivity in the overall economy and a large fall in the construction sector:

The earliest year in this data set is 1987, and the respective TFP estimates have each been indexed to 100 in 1987. Since then, total factor productivity for the overall private business sector grew to an index value of 136.3 as of 2023 and 138.1 as of 2024 – an average growth rate of 0.9% per year since 1987. Total factor productivity in construction fell, however, to an index value of 79.7 in 2023 – a fall of an average 0.6% per year since 1987. The figure for 2024 is not yet available. Had TFP grown in construction at the average for the overall private business sector, the construction sector in 2023 would be producing 71% more ( = 136.3/79.7) per unit of labor and capital input. That is huge.

Why did productivity fall (and fall by so much) in construction over this period? That is not normal. As noted above, one does not expect productivity to fall over time, as productivity comes from knowledge of how things can best be organized and produced. Knowledge over time only increases. It would certainly be possible (and indeed normal) that productivity growth will be faster in certain sectors than in others. But the mystery is not that productivity growth was slow in construction, but rather that it fell in absolute terms – and fell by a lot. And productivity fell despite the high profits among home builders, as discussed above. It cannot be attributed to a failure of not being able to fund investments to add to (or make more efficient) the capacity in the sector.

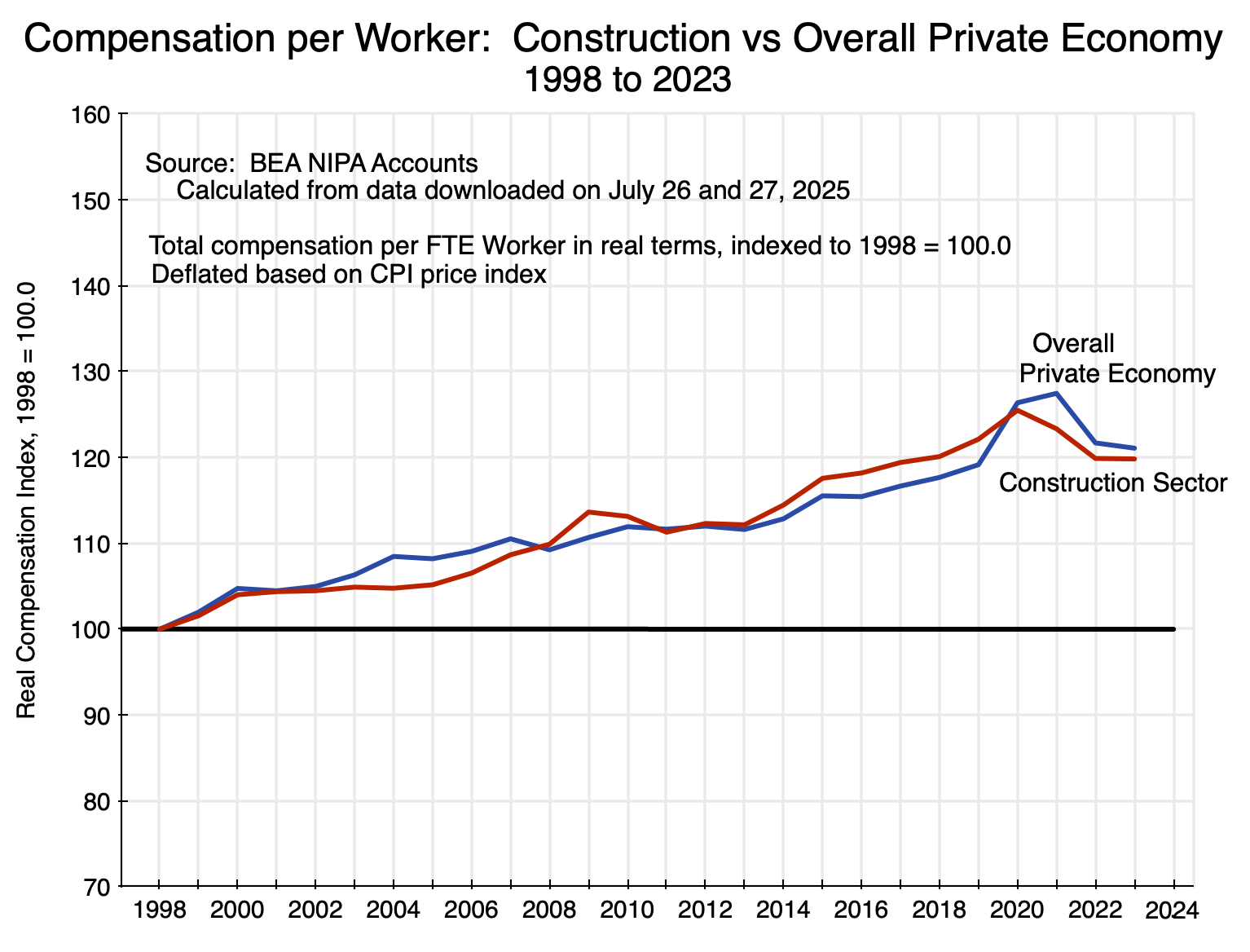

One possibility to consider might be that the cost of labor in the sector had gone down, perhaps due (in this theory) to immigrant labor driving down wages. According to the National Association of Home Builders, immigrants make up about one-quarter of all those employed in the construction sector (which would include office employees), and almost one-third of those in the construction trades themselves. Those shares are high. The argument might then be that with cheaper labor becoming available, home building firms chose not to invest in new machinery and equipment as they could instead use cheap – and perhaps increasingly cheap – labor to build the homes.

But total compensation per worker in the construction sector since 1998 has not gone down. It has gone up. And it has gone up at a remarkably similar pace as compensation per worker in the overall private economy:

Furthermore, while this is a chart of how compensation per worker has changed (in real terms) since 1998 in construction versus the overall private economy, it is also the case that the average compensation levels themselves were remarkably similar. In terms of current prices, average per worker total compensation (which will include the cost of benefits such as for health and pensions) in 1998 was $42,049 in construction and $41,694 in the overall private economy. In 2023, the rates (again in current prices) were $94,191 in construction and $94,373 in the overall private economy. And over the full 1998 to 2023 period, they never deviated by more than 3% from each other.

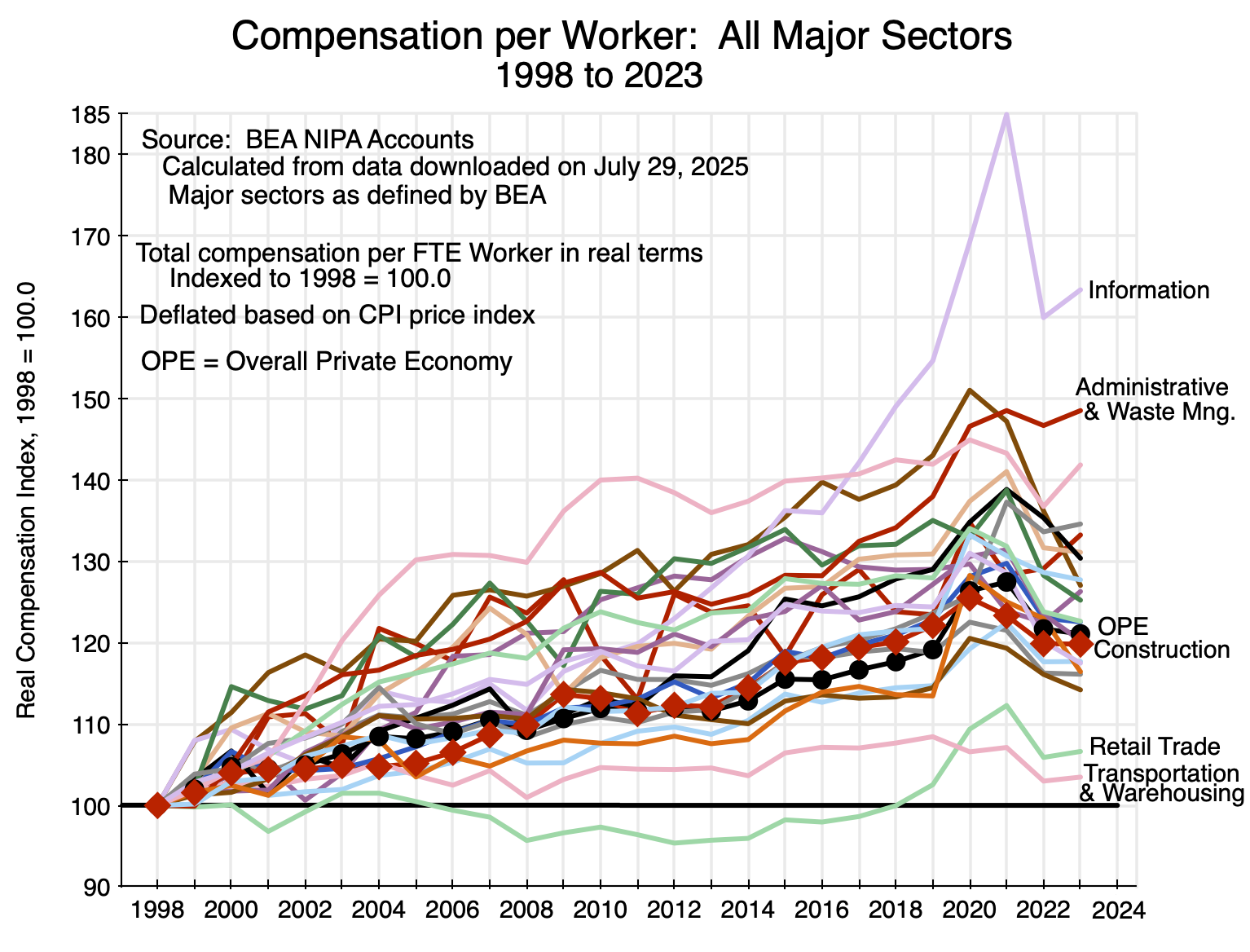

Thus wages in construction are not unusually low, nor did they increase at a slower pace than overall wage rates. And this was not a consequence of some economic principle linking sector wages to overall wages. In other sectors they could and did vary substantially from the overall average:

This chart is similar to Chart 11 above, but for all the major sectors of the economy (such as agriculture, mining, manufacturing, and so on) as defined by the BEA. The paths are all over the place. It just turned out that the figures for construction are very close to those for the overall private economy. There was no necessity in this.

Another argument some might make for the fall in productivity in construction is that regulations on health and safety conditions at the work sites have become increasingly strict in recent decades. It is probably correct that such regulations are stricter now than before – although I know of no figures or statistics that might measure this. But if the burden of such measures were indeed significant and increasing over time, and were the cause of the lower productivity seen in the charts above for the sector, then profitability in the sector would have gone down. Costs would be higher. But profitability has not gone down; it has been high.

So once again: Why did productivity fall in construction over this period, and fall despite profitability among home builders being especially high (so they could afford the capital investments had they chosen to make them)? The high profitability itself might provide a clue. One can conceive of productivity falling when home builders are not facing competitive pressures to stay efficient. Lacking competitive pressures, they can defer investments, build few homes in inefficient ways, but still see high profits as no one else is stepping in to compete against them. Put loosely, it is then easy to be lazy and not worry about producing for the lowest cost possible, as no one is pressuring you to do so. Fewer homes are being built than would be the case if the home builders were facing strong competitive pressures, but with fewer homes being built the prices of those they did build then rose to unprecedented levels. And profits could then be staggeringly high.

There will be less competitive pressure when a limited number of home builders in the relevant markets account for an increasingly higher share of the homes built in each of the markets. The next section will show that such consolidation has indeed been the norm in housing markets across the US.

F. The Increase in Home Building Firm Concentration in Local Markets

The relevant markets for home building are local – i.e. metro areas – and not national. This is key. It may look like there are numerous competing home building firms when viewed at the national level, but what is relevant to anyone seeking to purchase a home is not some “national” market but rather what is available in the area where one will live. Thus one needs to look at concentration in the new home markets not at the national level but rather by metro area.

Data on concentration among firms in local markets are rarely easy to access, if available at all. Fortunately, there is such data on home builders. Builder Online – basically a trade journal for home builders – provides figures each year (going back to 2005) on the share of the new housing market (in terms of the number of home sales closed) of the top 10 builders in each of 50 metro areas in the US. From this, we can track whether – and the extent to which – the home building market has grown more concentrated by metro area over the last two decades.

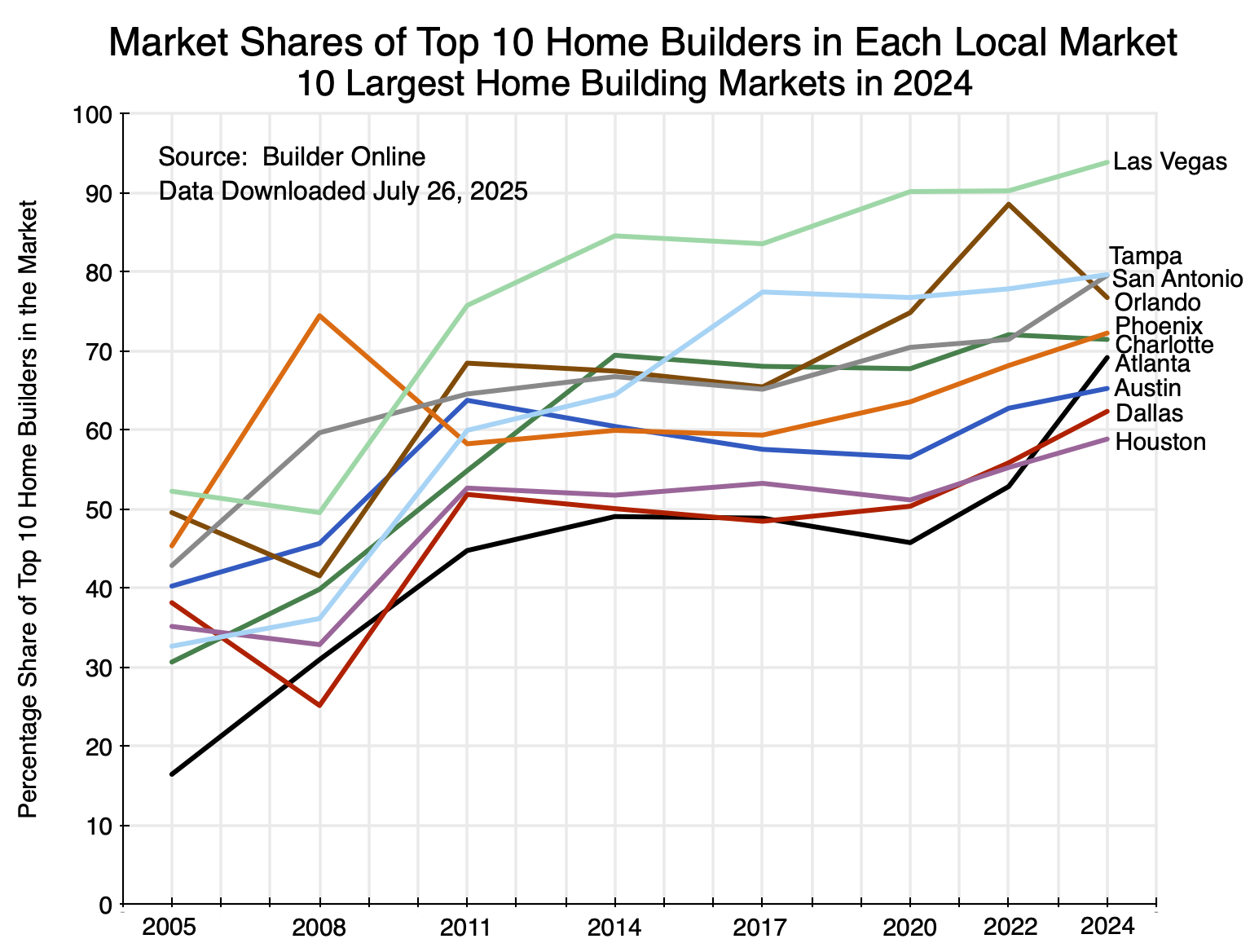

One can examine various sets of markets with these figures. For the 10 largest new home markets in 2024 (largest in terms of number of closings of newly built homes), we have:

The pattern is clear: Concentration rose in each of these markets over the last two decades. The increases were especially sharp between 2008 and 2011 following the economic and financial collapse of 2008/2009 (except for Phoenix, where there had been an especially large jump in concentration between 2005 and 2008). This increase in concentration also coincides with the point at which growth in the net stock of fixed assets fell below its previous trend path (Chart 6 above). The start of the sharp rise in home prices of recent years (shown in the chart at the top of this post) came soon after. The trough in the Shiller real home price index was in February 2012.

There was then a second jump in market concentration between 2020 and 2022, which may have been related to the disruptions surrounding the Covid pandemic crisis plus the very low interest rates of that period (making it easy to borrow to buy out competitors). The increase in concentration then continued in most of these markets between 2022 and 2024. In all of the markets the concentration was higher in 2024 than in 2020, and usually substantially higher.

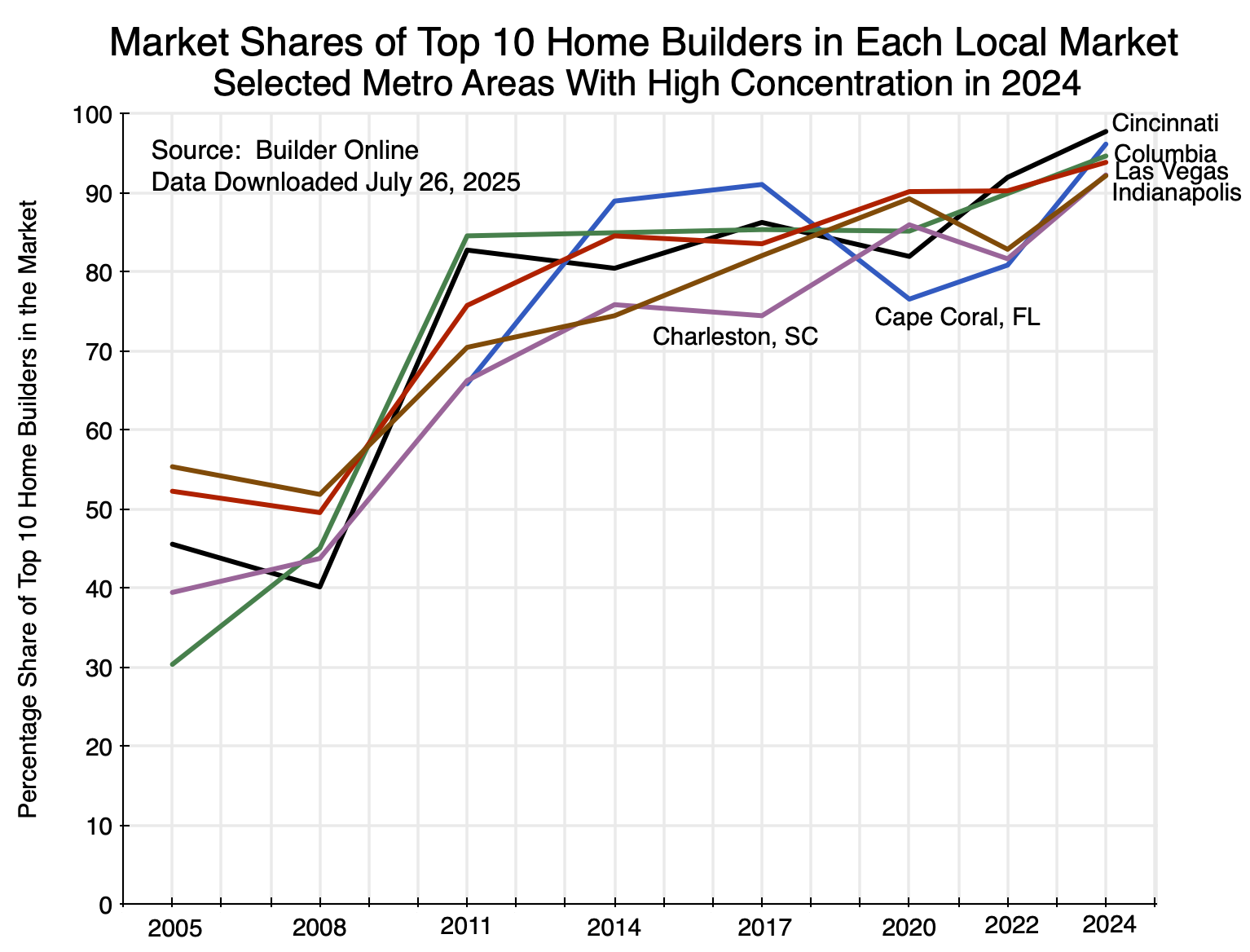

One can also look at other sets of markets. For example, 11 of the top 50 markets in 2024 saw market shares of the top 10 home builders in each accounting for more than 90% of the number of new homes built and sold. A few were among the smaller markets, but there was also:

One again sees the sharp increase in concentration between 2008 and 2011 and then a further increase after 2020.

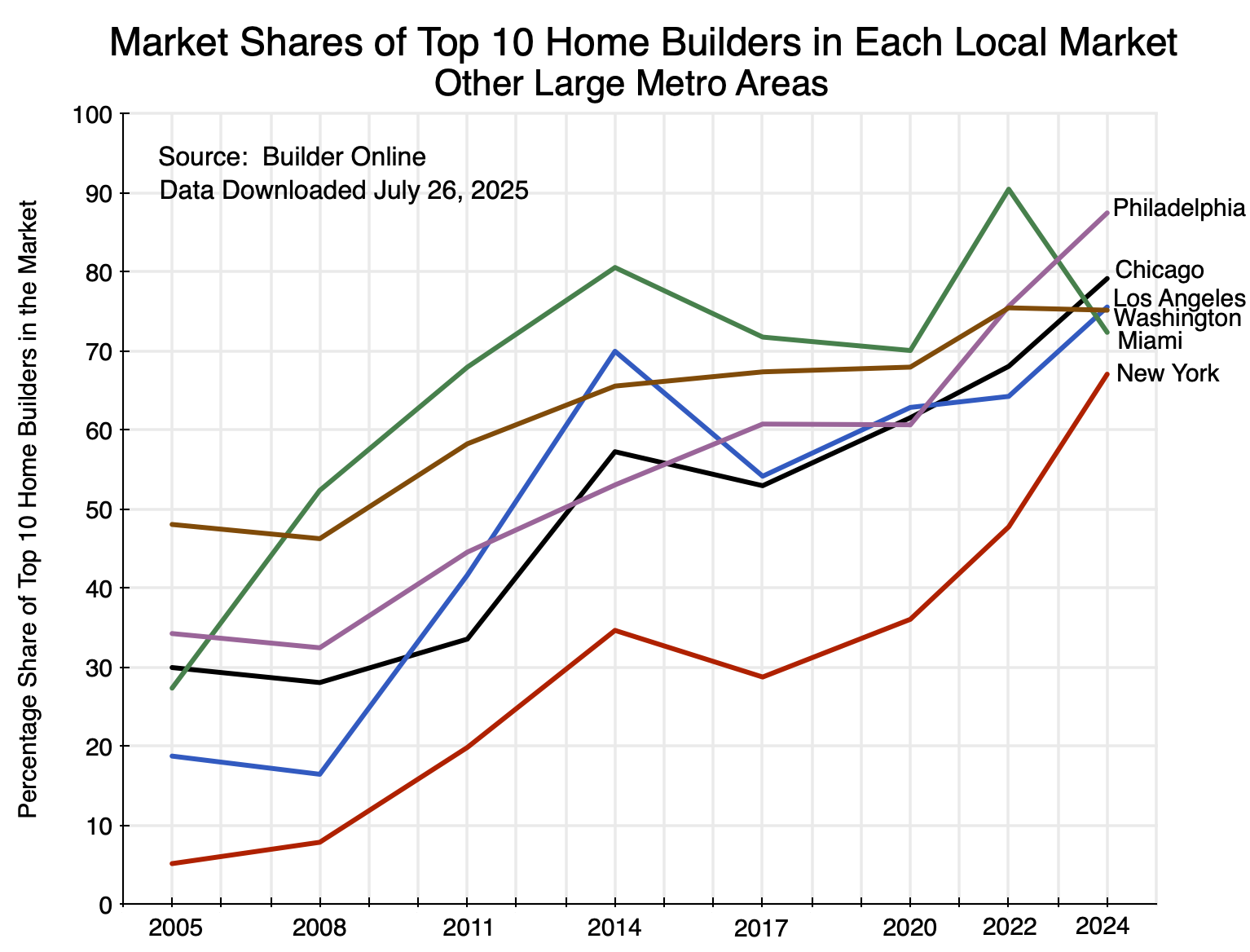

And in some other major markets:

The pattern is again similar.

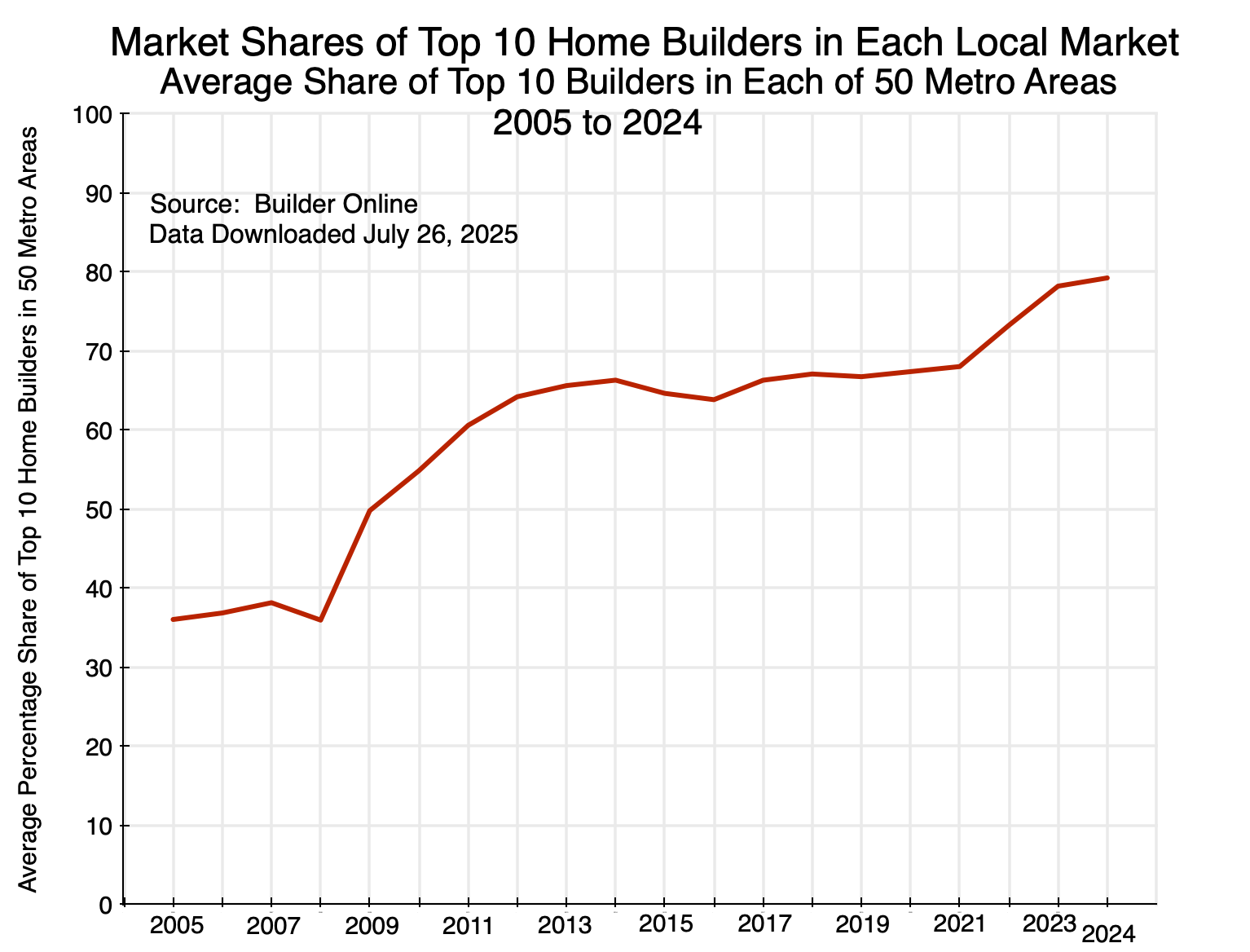

Finally, the pattern comes out clearly in the simple average of the top 10 home builder concentration across all of the top 50 housing markets in the US each year:

There was a large increase in concentration following the 2008/2009 economic and financial collapse, concentration then leveled off at those higher levels for a period, and then it rose again following the 2020/2021 Covid disruptions.

Home building markets by metro area have become substantially more concentrated over the past two decades. Fewer home builders are competing with each other in each metro area. This will reduce competitive pressures. While it is impossible to say what this might mean in absolute terms, what is relevant when looking at the impact on the pace of home building is what it means in relative terms over time. As we will discuss in the next section, with greater concentration production will be less than it would have been had the home-building markets not grown more concentrated.

G. Monopolistic Competition and Home Building

Markets for new homes are what economists call “monopolistically competitive” markets, and in this case one where entry of new firms is limited for some reason. Such markets differ from what economists call “perfectly competitive” markets – markets that represent more of an ideal than what one will normally see (with a few exceptions). In a perfectly competitive market, any supplier can sell all that he produces at some market price, and whatever amount he sells will have no observable effect on that market price. There are a few markets like this, such as a farmer growing a standard commodity such as wheat or soybeans. They can sell all the wheat or soybeans that they produce at the market price of that day and have no observable effect on it. If they try to ask for a higher price than that, they will not be able to sell any, and there is no reason why they should be interested in selling at a price lower than that market price.

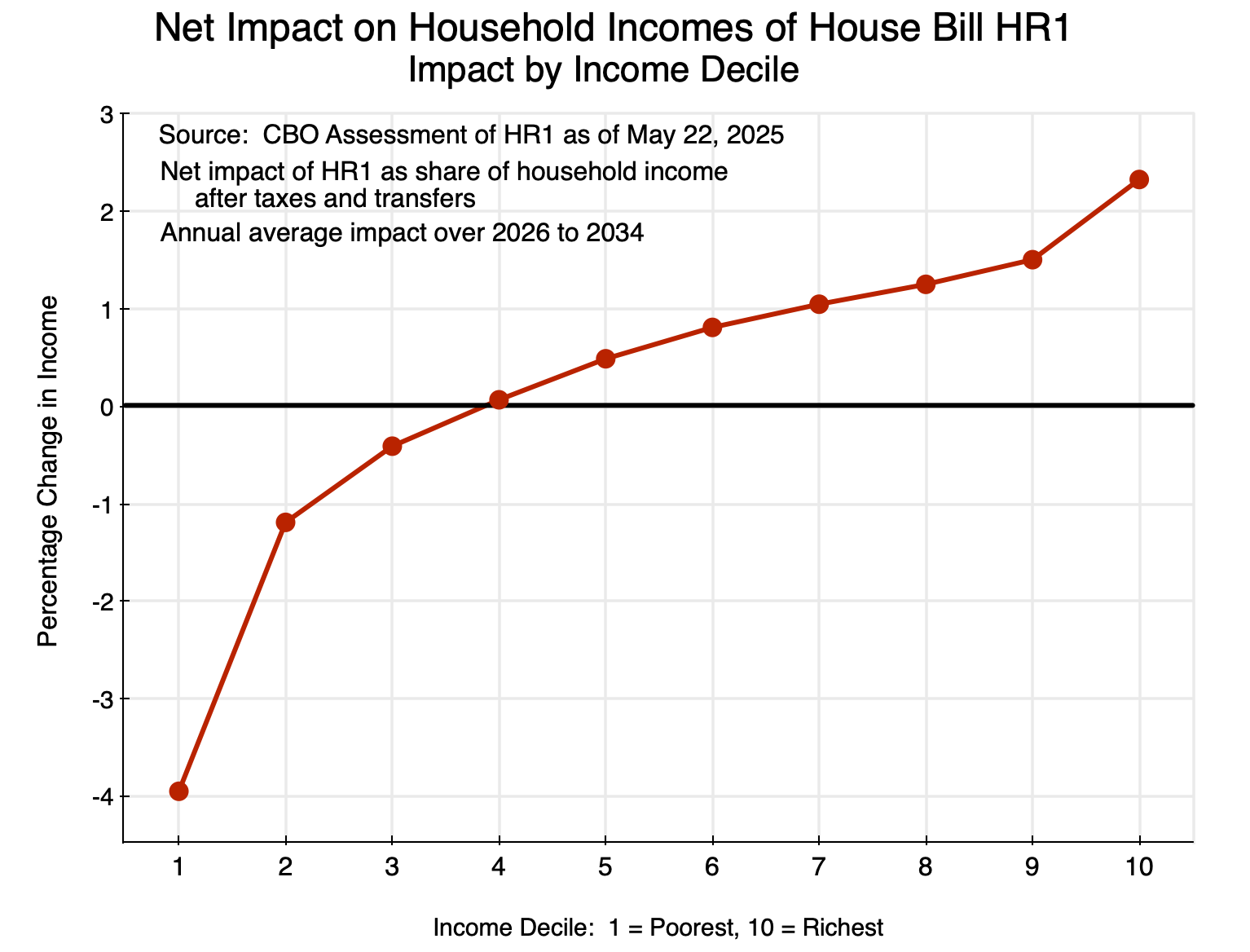

Homes, and most products in the modern economy, are different. Take breakfast cereals as a simple example. People have different preferences for different cereals from different brands, such as, for example, for Kellogg’s Corn Flakes. Because of this, if Kellogg should choose to raise its price by some small amount, most of those now purchasing the cereal will continue to do so, although some might switch to a different brand or a different cereal (or even no cereal). The fact that most consumers will still buy their Corn Flakes gives Kellogg some power to set prices where it chooses, a power that the wheat or soybean farmer does not have. Kellogg will then choose to price its Corn Flakes at a level that it finds most advantageous – meaning most profitable.

In a simple, static, system, Kellogg will choose to adjust its price to the point where the revenues it loses from lower sales (at the margin) from a somewhat higher price exceed what it saves in lower costs (again at the margin) from having to produce less due to those lower sales. That is, Kellogg will choose to price its product so that – at the consequent level of sales – its marginal revenues will equal its marginal costs. And at that point, it will be earning a substantial profit.

This is all standard economics, as taught in an introductory Econ 101 course on microeconomics. The Annex to this post works through this using standard supply and demand diagrams.

Homes are similar in that each one is different. Not only do different home builders build different types of homes, with at least perceived differences in quality and style, but they also build those homes in different places in any metro area. As any real estate agent will tell you, the three most important attributes in buying a home are location, location, and location. And by definition, every home built will be in a different location – with advantages and disadvantages to any interested buyer – even if the lots are adjacent to each other.

Home builders will thus have some degree of power to set prices for the homes they build. It is not absolute: If they price too high, they will not be able to sell any. But in general if they raise their price by some amount they will still be able to sell, but not as much as before (or, more properly for an asset such as a home, it will take them a longer time to make the sale, while they are incurring carrying costs such as interest on the loans they took out to build it). In such a monopolistically competitive market, they will be able to earn a substantial profit.

But the recent home building markets in the US then deviate from the standard model taught in Econ 101 classes for what will happen next. In the standard Econ 101 classes, students are taught that the high profits being earned by existing firms in those markets will attract new firms to compete with them. With that additional supply and competition, the excess profits that were first earned by the prior firms in the markets will be bid down, eventually to the point where no excess profits are being earned by any firms in those markets. The final outcome will still differ in some important respects from that in the model of perfect competition, but the main assumption is that excess profits will draw in new firms to the point where there are no more excess profits.

The home building markets in recent years have not behaved in this way. Instead of new firms entering the markets and thus making them less concentrated, the home building firms in those markets have been able to take an increased (not decreased) share of the relevant markets: the markets in each metro area. Mergers and acquisitions in the sector have been described as “red hot” in recent years and this has been underway for some time. In principle, enforcement of laws on competition should limit such consolidation, but the rules and regulations set by the federal government do not fit well with the conditions in the local markets of home builders. To start, concentration in the home builder market is not great at the national level. While the rules and regulations should in principle also apply in the smaller local markets, those are not always closely examined by national regulators.

Also important is that regulators do not focus on concentration at, for example, the top ten share. They focus, rather, on the share of an individual firm in the relevant market, with a normal “rule” that no individual firm accounts for more than 30% of the market. The assumption is that purchasers can easily switch to an alternative supplier from the 70%. Markets with ten competitors would normally be considered highly competitive. But there is not, in fact, such flexibility in purchasing a home. Due to the importance of location and other factors unique to each home builder, purchasers do not have an effective degree of choice such as they would have in purchasing, for example, groceries at ten different supermarket chains.

But for whatever reason, concentration among home builders has risen in the relevant markets over the past two decades. Relative to where it was in 2005, concentration in these markets are now all higher. And when there is an increase in concentration in the market (from whatever level), the home builders operating in those markets will be able to earn an even higher level of profits than they were earning before. They will be able to charge a higher price than before, and can adjust their prices (and the pace at which they build new homes) to take advantage of this. This is shown with supply and demand diagrams in the Annex to this post.

Finally, when markets have become both more concentrated and the demand for housing has increased (as it will with a growing population), their profitability will grow by even more. This makes intuitive sense as the limited number of home builders will see an increase in demand for what they produce, and is also shown diagrammatically in the Annex.

H. Putting It All Together

The story is straightforward. Local housing markets have become progressively more concentrated over the last two decades, with a small number of home builders accounting for higher shares of the relevant markets. They have been able to limit competition from new firms entering these markets, and hence the builders have been able to earn exceptionally high profits without those profits being competed away by new entrants. The lack of competition has also allowed them to function profitably even while they allowed their productivity to fall over time.

The result is that too few homes are being built. Or to be more precise, the result is that home building has not kept up with the growing demand from an expanding population. This became especially important following the economic and financial collapse of 2008/09, which was itself caused by the collapse of a housing bubble that had reached its peak in 2006/07. The result has been the unprecedented increase in home prices.

This does not mean that new home prices might, in the short run, fall from their current heights. As seen in Chart 1 at the top of this post, new home prices (in real terms) went dramatically up until the spring of 2022 and have since fluctuated around that high level. The spring of 2022 was when the Fed began to raise interest rates from the lows they had brought them to during the Covid pandemic in 2020 and 2021.

As a result, 30-year US home mortgage rates – which had been below 3% from mid-2020 through most of 2021, rose to over 7% by late 2022 and into 2023.. As I write this, they are still at around 6 1/2%. The higher mortgage rates mean that a purchaser who needs a mortgage will pay much more each month on that mortgage, even if the home price is the same as before.

This would normally lead to a reduction in home prices. The fact that they have remained largely unchanged over the last three years is unusual, and can be explained by special factors. One is that those with a low interest rate mortgage – taken out or refinanced when interest rates were low – will be reluctant to sell that home and move to a new one as they would then need to take out a new mortgage at the current much higher rates. This has reduced turnover and increased rigidities in the housing markets.

But home prices might fall from their current heights at some point in the next year or two. While the long-term trend for new home building has been down (Charts 4 and 5 above), there has been an increase since around 2012 as construction emerged from the depths of the 2008-2011 collapse. This might eventually have an impact on home prices.

Such short-term fluctuations should not be surprising, and are in fact the norm for home prices. But one should not confuse such short-term fluctuations with the long-term trend in home prices of the last few decades. And that trend is up.

Before ending, I should mention an alternative argument for why home prices have risen by so much in recent years. This argument puts the blame on local housing regulation, asserting that these regulations have become more stringent over time and are primarily responsible for the lack of adequate new housing being built despite the record high home prices.

These arguments have been made under the label of the “Abundance” agenda – a term that came from the title of the recent book of Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson (although they address more than just housing). It is also behind what has been called the “Missing Middle” and similar terms. The Missing Middle agenda is that home builders should be given the option to build higher density structures (e.g. small apartment buildings) on the existing land footprint of areas now occupied by single-family homes.

It is not my purpose here to address these arguments in full. Local land use policies can certainly matter, and increased concentration of home builders in their local markets and changes in land use policies may both have had an impact on home prices. But I do not see the basis for arguing that only local land use policies (and other increasingly costly or restrictive regulations) have been the cause of high home prices:

a) If the constraint on the building of more new homes comes from restrictions on the use of available land, then the ones who will profit from this are not the home builders (who must purchase land for any new home construction, including for what is being built now) but rather the land owners. That is, this would not explain why home building itself has become so highly profitable. What economists call the “economic rents” here will be accruing to the land owners, not the home builders.

b) One can see why owners of available land may welcome the chance to sell their lots for high density development. They will be moving elsewhere, and it will be those who continue to live in the neighborhood who will bear the costs of greater congestion and pressure on public infrastructure, and have to live with fewer trees and other green space in their neighborhoods. The benefits of a pleasant neighborhood are basically an externality produced by all the lots in the neighborhood. Converting the first lot to a high density structure will reduce that marginally. But as more and more are converted, the value of that externality will be steadily reduced and property values will go down.

c) This may well lead to lower home prices in the neighborhood, both due to the greater supply and due to the neighborhood not being as pleasant as before. Homeowners who have not moved will bear that cost. But this is basically a zero-sum (indeed possibly negative-sum) game: The benefits to those now able to move in at a lower cost (and those who sold their lots and moved away) will be offset by the losses of those who had lived and remain in the neighborhood.

d) An alternative approach would be to follow a transportation (or transit corridor) oriented development policy. Rather than placing high density structures into the middle of low density neighborhoods (where the newcomers will need to rely on cars to get around), development should be directed to neighborhoods built up along transit corridors. The transit corridors could be rail lines in certain cases, but more commonly various levels of bus service from standard up to express or bus rapid transit services. There is substantial low density commercial development (surrounded by large expanses of surface parking lots) around all American cities. Diverse neighborhoods could be developed on such land, with the highest density close to the main transit stops and lower density as one goes further away.

As noted, land use constraints – either by changes in land use regulations or simply a matter of space being used up as cities have grown – may be a contributing factor to higher home prices. But they do not explain why home builders have been so highly profitable. More fundamentally, if land use constraints were the primary cause of the higher home prices now observed, one would expect this to have led to a gradual but steady increase in home prices over several decades, rather than the sharp jump observed more recently. Residential assets had risen on a steady trend up to around 2007 (Chart 6 above). The question is what caused the deviation from this trend that began in 2008 and was then sustained. The observed increase in market concentration of home builders in individual metro areas after 2005 can explain this.

A natural question is what to do now in terms of policy. That has not been the focus of this post, where the aim was to examine what has led to our current very high home prices. Nor are there any easy answers. But a few points can be made.

First, as the proverb says: “When you’re in a hole, the first thing to do is stop digging”. Home building has become a substantially more concentrated industry in individual local markets in recent decades, and more serious enforcement of competition policy could stop this from getting worse. That should be done. It will be more difficult to unwind this to return to the less concentrated markets of the past, but measures might be possible to encourage greater competition between home builders. Signs of collusion should be monitored.

Beyond this, government has a direct role to play in developing and expanding transportation corridors where new, diverse, neighborhoods can be developed (with a mix of high, medium, and low density). New housing would be built and would add to available supply. Development of such corridors depends on public investment, primarily in the development of suitable public transit options (which can vary, as noted, from bus service at an appropriate standard to rail options). Government plays a direct role in making such development possible.

The bottom line is that there is a need to ensure more housing is built. Transit-oriented development can be a key part of this. Government can play an important role here and needs to.

Annex: Supply and Demand Curves Under Monopolistic Competition

Firms (such as home builders) can make substantial profits under conditions of monopolistic competition. And those profits can be sustained if the entry of new potential competitors is limited for some reason. Furthermore, under such conditions the profitability of the home builders will increase if the markets become even more concentrated (with a small number of home builders accounting for an increasing share of the relevant markets), and even more so if demand is also growing.

This annex will back up each of these propositions via standard supply and demand diagrams, the same diagrams that anyone would be taught in an introductory Econ 101 microeconomics course. They will be built up in steps, starting with the most simple situation (the assumption of perfect competition) and moving from there by steps to the more complex. In the end, the shifts in the supply and demand curves may look complicated, but they in fact simply reflect a step-by-step buildup.

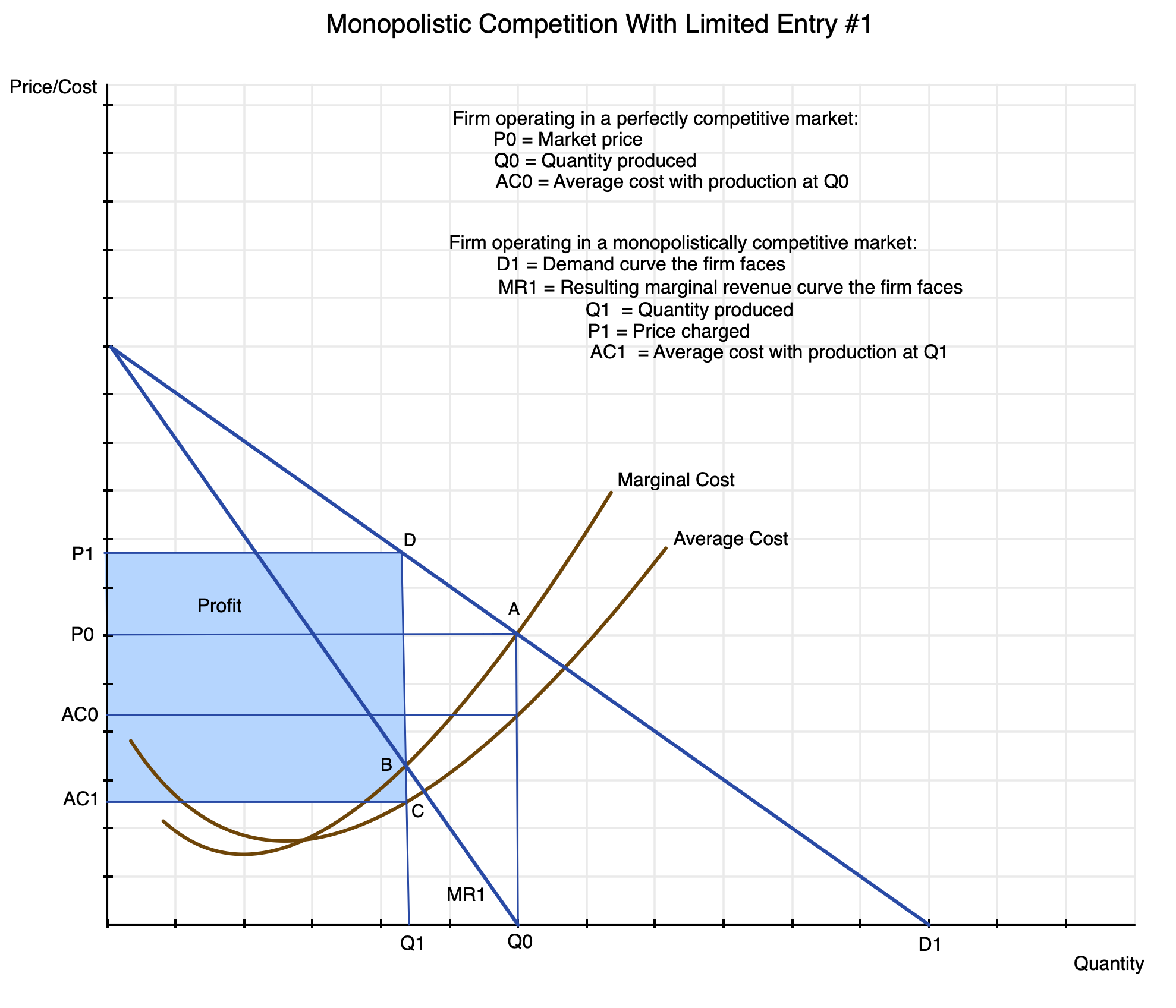

Note also that this supply-demand diagram (and the subsequent ones below) are for what an individual firm faces. While such diagrams are sometimes used to depict conditions in a sector as a whole, that is not the use here.

Economists start with the assumption that the firm operates in a market of perfect competition. This is not because such markets are common or even realistic, but rather because they provide a starting point as a basis of comparison. As discussed in the text, under perfect competition a producer can sell all that he wishes to produce at a certain market price, and whatever he sells will not affect that price. One can find such markets in cases such as farmers selling a standard commodity (e.g. wheat or soybeans). In such markets, producers will choose to produce and sell up to an amount where their marginal cost of producing the good will equal that market price.

In cases where products are differentiated for any reason (e.g. brand identity, differences – actual or perceived – in what the product actually provides or in quality, and for any other reason), the producer has some power to set the price at which they will sell their product. If they raise their price by some amount, the total amount they can then sell may go down (and likely will go down) by some amount, but not immediately to zero. Thus they have some degree of flexibility to decide what price to charge for their particular product (such as a new home of a certain design and quality in a particular location).

The situation is then depicted in the following supply and demand diagram:

First, if this were in fact a perfectly competitive market, the producer would choose to produce a quantity Q0 which it could sell at a price P0: that is, at point A in the diagram. Their marginal and average costs of production are assumed to follow the curves shown (rising with increasing production after some point). The demand curve they face (not explicitly shown) would be a horizontal line at price P0 – the market price they face which they cannot affect through how much they choose to sell. Since they can receive price P0 for whatever amount they offer, they will choose to produce and sell as long as their marginal cost of production is less than the price at which they can sell it, and thus will produce Q0.

The firm being depicted here will also be making a profit when they produce quantity Q0 that they sell at price P0 (i.e. at point A in the diagram). Their average cost of production is less than their marginal cost at that point, and the profits they would then be earning would be the quantity produced Q0 times the difference between the price they receive P0 and their average cost at that level of production AC0. In general, both the average cost and marginal cost curves will be rising at that point, with the marginal cost curve above the average cost curve. Indeed, the marginal cost curve will pass through the lowest point of the average cost curve, since average cost will be falling as long as the marginal cost is below it and rising as long as the marginal cost is above it.

When the firm operates in a market with product differentiation, in contrast, the demand curve they will face is not horizontal (at price P0), but rather some downward sloping curve such as the one depicted here as D1. For simplicity, it is drawn as a straight line, but in general it can be any curve that slopes downward throughout. The demand curve shows how much they will be able to sell in a period for any given price. Or put the other way, it shows what price they will be able to obtain for any given quantity that they choose to provide.

Their decision on how much to produce and at what price now differs from the case of perfect competition. What matters now is what revenue they will earn – at the margin – at any given level of production (with the associated price they can charge at that level of production). If they scale back production by some amount, they will be able to charge and receive a higher price. Or put the other way, if they choose to charge a higher price, the amount they will be able to sell will be reduced by some amount.

The average revenue they will earn for sales of any given quantity will simply be the price they can get at that level of sales (i.e. what is shown on the demand curve). Hence the demand curve can be referred to as the average revenue curve. But the marginal revenue they will earn when they charge a higher price will be less than that price since the quantity they can sell will be less. Hence for any given quantity along the horizontal axis in the chart, the marginal revenue curve will be below the average revenue curve.

And that is all that we need to know. In the special case where the demand curve is a straight line, one can easily show (as is always done in the introductory Econ 101 microeconomics class) that the marginal revenue curve will also be a straight line with a slope that is twice the negative slope of the demand curve (average revenue curve). This is a result of some elementary calculus that will not be repeated here. For the purposes here, all one needs to understand is that the marginal revenue curve will be uniformly below the associated demand (average revenue) curve.

A firm facing such supply and demand conditions will then choose to scale back production to the point where their marginal cost of production will equal the marginal revenue they will earn from that production. That is, they will not remain at a point such as A, as at that point their marginal cost is higher than the marginal revenue that they earn at that level of production. (In the perfect competition case, where the demand curve they face is not the D1 curve shown in the diagram but rather a horizontal line at price P0 – as noted before – their marginal revenue curve will also be a horizontal line at that same price P0. The slope of the demand curve is zero, and the slope of the marginal revenue curve – which is double that of the demand curve – will also be zero as double zero is still zero.)

Producing a quantity Q0 for sale at price P0 will therefore not be as profitable to them as scaling back production to Q1, where their marginal cost is no longer higher than the marginal revenue they can earn but rather equal to it. This is point B in the diagram. Or going from the opposite direction, they will expand production as long as the marginal revenue they earn at that level of production exceeds their marginal cost of producing it. And they will stop expanding at the point where their marginal cost becomes equal to their marginal revenue.

When they are producing at point B with quantity Q1, their average cost of production will be at point C with cost AC1. And they will be able to sell their output at point D on the demand curve, i.e. at price P1. Their profits will then be equal to quantity produced Q1 times the price they will receive P1 minus their average cost AC1, i.e. the area shown in the box in light blue in the diagram. They are producing less than they would in a situation of perfect competition, but they are receiving a higher price and their average cost will be less. Since their marginal revenues are below their marginal costs for production above that point, scaling back production to Q1 from what it would be under perfect competition will always be more profitable for such firms.

[And as a point of clarification: The particular way I drew the diagram here has the marginal revenue curve MR1 intersecting the quantity-axis in the chart at the same point as quantity Q0. This is a coincidence, and will not in general be the case. It happened here as I drew the initial point A at a center-point in the diagram – six units on each axis – and the demand curve as a 45-degree line. The quantity Q0 will then be at the same point where the MR1 curve hits the axis. This will not in general be the case, but I did not want to redraw all the charts.]

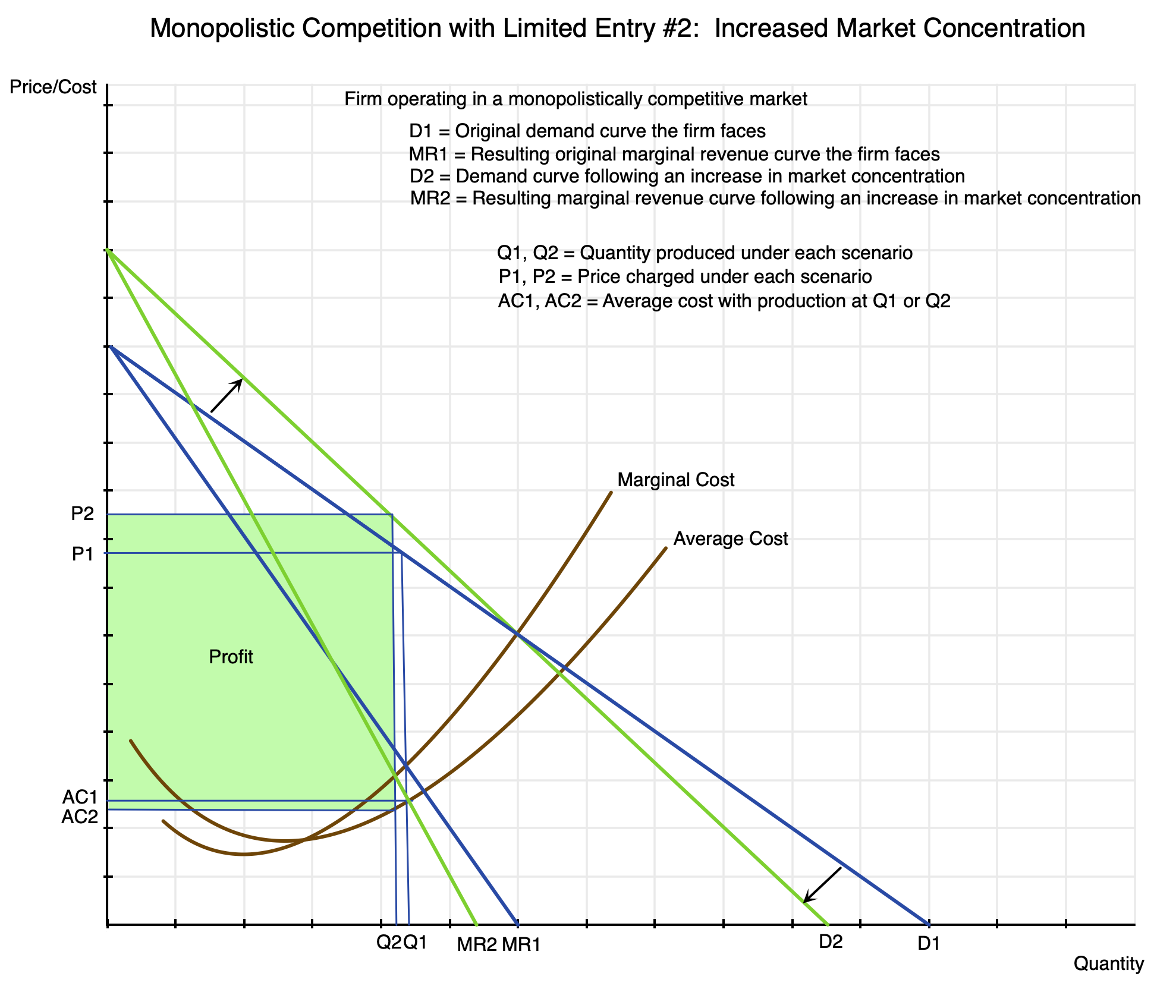

Starting from this, one can then look at what will happen to the firm’s choice on how much to produce (and the impact on its profitability) if the market should become even more concentrated. This now deviates from the standard textbook treatment of monopolistic competition, in that in the standard treatment, it is assumed that the high profit the firm is able to earn (shown as the box in light blue in the chart above) will attract new competitors. The new competitors will add to production in the market, which will lead the prices to be bid down and possibly increase costs for all (as they compete to buy some of the inputs needed in production). This will reduce profits for the firms, and it is assumed (in the standard treatment) that new entrants will continue to come in as long as exceptional profits are being made.

But the home building industry has become more concentrated rather than less in the relevant local markets for new homes, as discussed in the text. And by being able to increase concentration in those markets, home builders will become even more profitable than before.

This is shown in this second supply and demand diagram:

In a more concentrated market, the home builder depicted here faces less competition than before. Should he raise his price, the amount he will be able to sell will still be less, but not as much less as before. With fewer competitors for the purchaser to turn to, the firm will be able to keep a higher share of its customers (should they raise their prices) than would have been the case had market concentration not increased.

The result is that the demand curve for the firm will “twist” clockwise relative to where it was before – i.e. become steeper. Their demand curve will now be the one in green (D2) rather than the one in blue (D1). The associated marginal revenue curve will similarly twist to MR2 from MR1. Their profit maximizing point will be where their new marginal revenue equals their marginal cost, and this point will have shifted to the left, with production now at Q2 rather than Q1. (I left out letters to label the intersection points as the chart would have been too crowded with them.) With lower production, the associated average cost AC2 will be below the prior AC1. And the price they will be able to charge will now be P2 – above the prior P1. Prices of new homes will be higher. Profits will be higher as well, and are shown as the box in green in the chart.

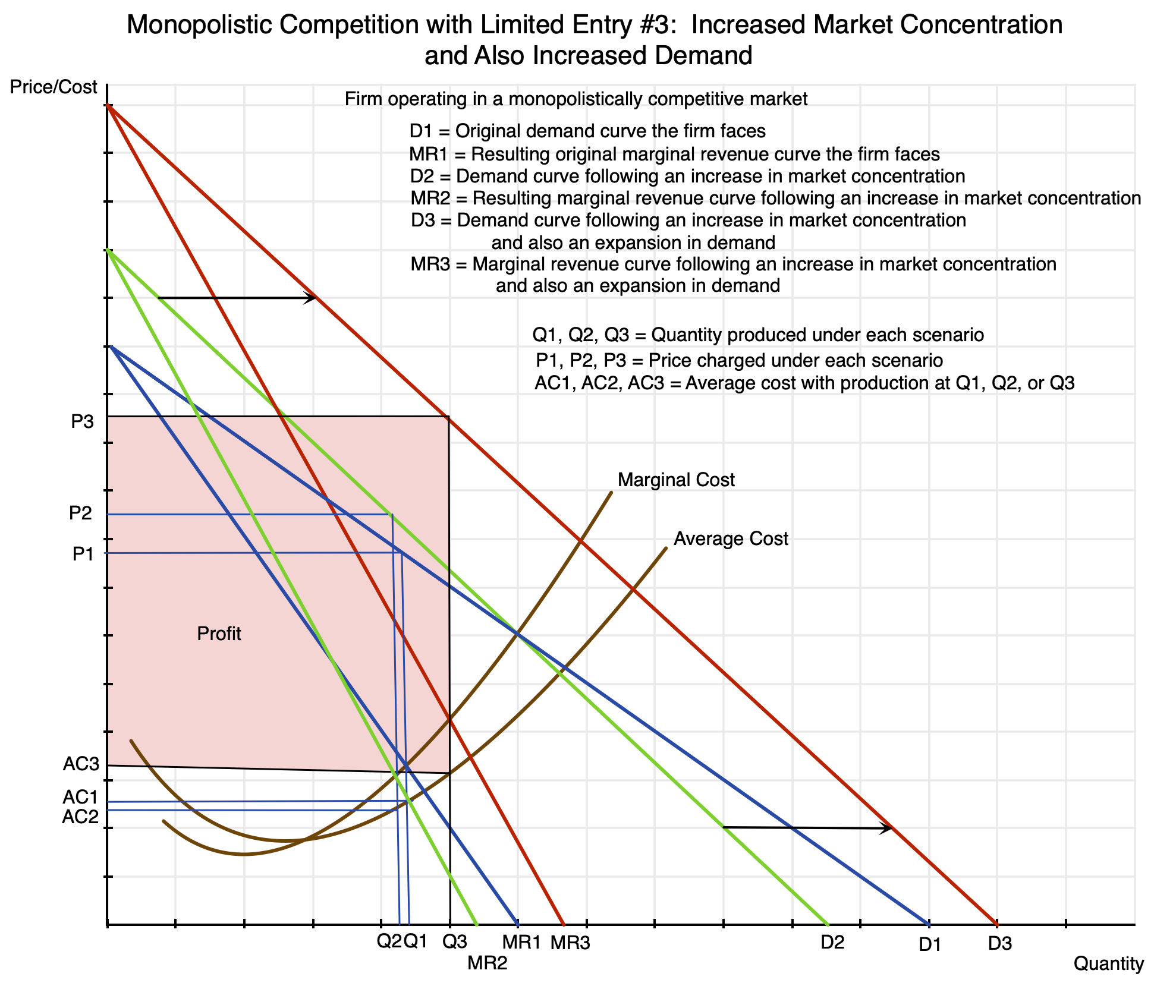

Finally, if there is an increase in demand over time while the home building market is becoming more concentrated, new home prices (and profits) will grow by even more:

In this comparison, both concentration among home builders in the local market and the demand for homes in that market have increased. Due to the growth in demand, the demand curve has shifted to the right from D2 to D3. Production would rise from Q2 to Q3, i.e. to where the marginal revenue curve MR3 intersects the marginal cost curve. The average cost AC3 will be higher due to the rising average cost curve. But the price will be substantially higher, rising to P3 from P2. The firm’s profits will now grow to the area shaded in pink. They can be much larger.

It is worth noting that while production will have gone up (from Q2 to Q3), that increase in production is less than the growth in demand. The increase in demand can be measured by how much higher demand would have grown to at a constant price (the starting price of P2 – although this does not matter in the simple example here of a straight line demand curve shifted out by the same distance at all prices). With a rising marginal cost curve as well as a falling marginal revenue curve, the increase from Q2 to Q3 will always be less than the distance that the demand curve has shifted at the original price of P2. Or put another way, demand is constrained to grow from Q2 to Q3 rather than what the increase would have been at a constant price, by the producer raising the price from P2 to P3 in order to raise production and sales only to the point where his marginal revenue is equal to his marginal cost (i.e. only to Q3).

Note that with the growth in demand and an unchanged average cost curve, the average cost will go up (from AC2 to AC3). This could be due to lower productivity at the higher demand (due, for example, to inadequate investment), but this could in principle be due to other factors as well.

You must be logged in to post a comment.